Beatriz Martin’s first job at UBS Group AG was to help shrink the investment bank after a $2 billion loss from a rogue trader. Eleven years later, Chief Executive Officer Sergio Ermotti is turning to her again for a key role in the biggest restructuring in global finance.

Ermotti is tasking the 50-year-old executive with the job of sifting through the assets of Credit Suisse Group AG and deciding which ones to keep and which to wind down. Her success is critical in ensuring the CEO can make good on his promise to taxpayers that they’ll avoid a hit from the historic, government-brokered rescue of the smaller rival.

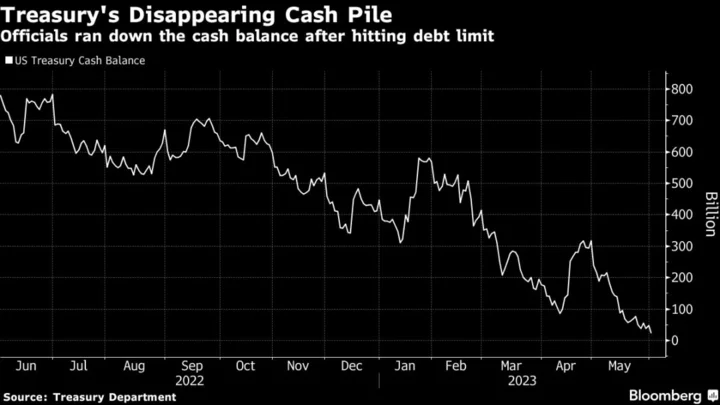

The challenge for Martin, who joins UBS’s executive board, will be to minimize losses from disposals and wind-downs in what’s likely to be a bulky and complex non-core unit. The bank will take the first 5 billion francs of such losses, while anything more would leave UBS tapping into a 9 billion-franc Swiss state guarantee.

Such a move wouldn’t just be politically fraught, it could also jeopardize banker bonuses. The Swiss government has ordered UBS to make sure its own pay structure encourages employees handling the sale of unwanted Credit Suisse assets to maximize profits and avoid losses that would invoke the guarantee.

Such losses are “exceptionally unlikely,” Ermotti said at an event Friday, adding the bank will “do everything” in its power to avoid taxpayer support.

Swiss Are On the Hook for $13,500 Each on Credit Suisse Bailout

The comments, before the bank has even had the chance to properly go through the books, underscore the pressure on Martin, a UBS veteran who joined in 2012. At the time, the firm had just begun the difficult process of slashing the investment bank, after a bailout during the financial crisis and losses triggered by rogue trader Kweku Adoboli.

Ermotti was at the helm of the bank at time, driving the pivot from investment banking to the less volatile business of wealth management. As chief of staff to Andrea Orcel, the head of UBS’s securities unit who now runs Italy’s UniCredit SpA, Martin was focused on separating “the good bank from the bad bank,” she recalled in a 2018 interview with Waters Technology.

“We looked to decide what to do with the fixed-income business and also bravely define what we are not going to do,” she said in the interview with the online news site. “The implementation of that was fast — it was painful but it was fast.”

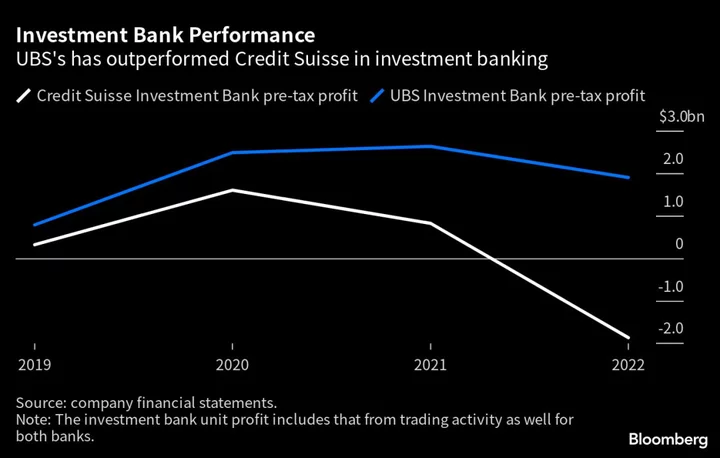

Today, Martin is one of the few executives still around from that period and she will now be the main protagonist sifting through Credit Suisse’s money-losing securities unit, with fixed income trading once again a focus. Credit Suisse had already placed some businesses in a wind-down unit before the rescue, but UBS is expected to take a much broader approach to bring risk-weighted assets at the investment bank to around 25% of the group, about what it was before the deal.

UBS has indicated it’s seeking to cut back riskier trading operations and will be “extremely selective” in taking on trading and derivative assets. Areas it wants to keep include Credit Suisse’s strengths in US advisory and the technology sector. UBS is interested in beefing up its tech bankers to better capture the wealth business of technology entrepreneurs.

Current and former UBS colleagues say Martin is well-equipped to handle the difficult decision making that comes with separating the good from the bad, unwinding complex trades and loans, and cutting the jobs that are no longer needed. As a former trader — she cut her teeth in fixed-income at Deutsche Bank AG and later Morgan Stanley — Martin won’t be fazed by technical details, a former senior colleague said.

Another former UBS colleague who worked with her for more than a decade said Martin was good at taking difficult decisions and has expertise in separating businesses that don’t require a lot of the bank’s capital from those that do. Some describe her as someone who embraces challenges and likes to challenge others.

UBS declined to make Martin available for this story.

An energetic person with a direct, hands-on approach and an open-door policy, according to the people, Martin parlayed her role as chief of staff into a job as chief operating officer of the entire securities unit within two years. She later added the position of chief executive of UBS’s UK operations.

When she moved into the role as group treasurer in 2020, Martin helped develop the bank’s first “digital” bond, which became the first ever bond of its kind to be publicly traded and settled on both blockchain-based and traditional exchanges.

Now tasked again with scaling back a large investment bank, her career at UBS has come full circle. UBS has said the integration work could take up to four years. It expects $8 billion in cost savings, with about $6 billion coming from job reductions. Many of those will probably occur in Credit Suisse’s investment bank, which employed 17,000 at the end of last year. UBS had just over 9,000 full-time positions in its securities unit.

UBS Chairman Colm Kelleher, who brought back Ermotti to oversee the deal, has said that the task of integrating Credit Suisse is bigger than any takeover that was executed during the height of the financial crisis in 2008, and warned of “significant execution risk.”