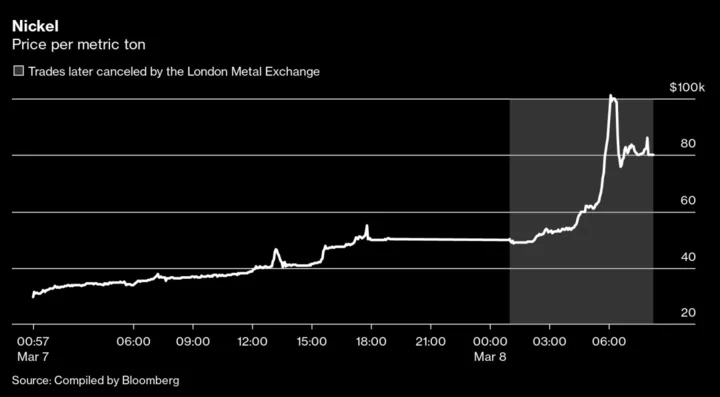

The London Metal Exchange contributed to last year’s nickel crisis by removing trading curbs just as prices spiked up in a massive short squeeze, according to the two firms suing the LME over its decision to cancel billions of dollars of trades a few hours later.

The unexplained removal of “price bands” early on March 8 meant that nickel was able to rise much faster than it normally could have, Elliott Investment Management and Jane Street argued in filings Tuesday. It was among a barrage of accusations launched at the LME over its actions last March, on the first day of hearings in a case that’s likely to decide the future of the world’s key metals market.

Read more: The World’s Most Feared Investor Faces Showdown Over Nickel

The LME didn’t have proper monitoring of the market during the Asian session despite nickel already having rocketed higher a day earlier, the firms said. By roughly 6 a.m. in London, nickel had soared 250% in little over 24 hours. But when LME Chief Executive Matthew Chamberlain woke up and suspended the market after failing to find a real-world explanation for the breathtaking surge in prices, he wasn’t actually aware that the exchange’s circuit breakers had been removed.

A few hours later, and still in the dark over the price curbs, Chamberlain made the controversial decision to cancel the day’s nickel trades — worth about $12 billion according to Jane Street. The move served to bail out metal tycoon Xiang Guangda and his banks, while preventing what the LME has called a potential “death spiral” of defaults by members. But it has drawn furious criticism, including from investors such as hedge fund Elliott and trading firm Jane Street that were selling at sky-high prices on the morning of March 8, and stood to reap huge profits.

Read more: The 18 Minutes of Trading Chaos That Broke the Nickel Market

Their day in court finally arrived on Tuesday, as lawyers for the two firms face off against the LME in the first of three days of hearings in London’s High Court. Elliott, the hedge fund founded by legendary activist investor Paul Singer, is seeking $456 million, while Jane Street has a much smaller claim at $15 million.

The companies are seeking to have the cancellation declared unlawful by a panel of two senior judges, arguing that Chamberlain rejected alternative courses of action that would have been less damaging for the market.

For the 146-year-old LME, the judicial review is only part of the fallout it continues to navigate, more than one year on from the nickel crisis. The exchange is also facing a rare probe from the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority over its handling of the debacle, while the world’s benchmark nickel market itself has yet to return to normal.

The LME has said the judicial review has no merit and the complaint is “based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the situation.” Chamberlain considered that the market had become “disorderly,” and had no choice but to suspend and cancel the trades to avoid a $20 billion margin call, that could have triggered a cascade of defaults, it said.

“Exchanges are legally required to maintain market order and to have the power to cancel trading activity in response to exceptional market events,” the LME’s lawyers wrote in a filing Tuesday. “It is almost inevitable that any exercise of those powers will be controversial and will have serious financial consequences for those affected.”

Read more: Elliott’s Fight With LME Has Rivals Cheering From Sidelines

The exchange disputes that the trading curbs — or their removal — had a material effect on the day’s events, and says the information wouldn’t have affected Chamberlain’s decision making either way.

The controls in question, called price bands, are designed to stop orders from being executed at prices that are significantly above or below the last traded price. They’re typically used to prevent “fat finger” orders that have been entered by mistake, but they were frequently being triggered on March 8 as liquidity evaporated and prices started to jump by hundreds of dollars at a time.

The LME’s operations team repeatedly adjusted the bands, and ultimately suspended them at 4:49 a.m., around the time that nickel was beginning its steepest spike to beyond $100,000 a ton.

Chamberlain himself says he woke up at around 5:30 a.m., checked his emails and searched for information “which could provide any type of rationale for the price moves.”

Around that time, a broker dealing on behalf of Tsingshan Holding Group Co. — which had amassed a huge short position in nickel and was facing billions of dollars in losses — told Chamberlain in an email that he needed to cancel the day’s trades and reset prices at the much lower levels seen at the close of the prior day’s trading.

The LME said Chamberlain wasn’t influenced by the email from the unidentified broker, or interactions with other LME dealers that morning. Elliott and Jane Street argue the LME should have consulted with the market more broadly before deciding on a course of action.

The LME held an online meeting at which other options were examined and rejected, before Chamberlain took the decision to cancel the trades. Elliott and Jane Street’s lawyers have zeroed in on one potential option in which the LME would allow the March 8 trades to stand, but set margin by reference to a different, lower price. The two firms argue the plan would have been less harmful to the market, while the LME says it wasn’t viable.

--With assistance from Jack Farchy and Mark Burton.