When a team of Israeli technocrats that calls itself the “government’s CFO” scans the battlefield with the war against Hamas almost seven weeks in, it sees an accounting ledger with billions of debits stacking up.

Their job is to find the money to help pay for it all.

As Israel’s military pushed deeper into Gaza with the goal of uprooting Hamas following its Oct. 7 attack, the Finance Ministry’s accountant general department was fine-tuning forecasts and updating the government’s running tab in real time by logging the costs of every missile interceptor, every flight and every day of deployment by reservists.

Those expenses are quickly adding up, even as a hostage deal with Hamas now holds out the prospect of a four-day pause in the fighting.

The war, which the Finance Ministry estimates is costing the economy around $270 million every day, will come with a fiscal price tag estimated at 180 billion shekels ($48 billion) in 2023-2024, according to Leader Capital Markets, a financial advisory powerhouse in Israel.

Israel will likely be on the hook for two-thirds of the total costs, Leader said, with the US paying for the rest.

Israel’s fiscal math means the government will largely have to borrow its way through what’s already its worst armed conflict in half a century. And the man in charge of managing Israel’s $300 billion debt stock is mindful of the risks.

“We are moving forward with a base case scenario that references several months of combat and have worked in additional buffers,” Yali Rothenberg, the Finance Ministry’s accountant general, said in an interview. “We are well capable of financing the State of Israel even in more extreme scenarios than the current fighting.”

The fiscal shock is cascading through an economy that had to shift to a war footing in a matter of days after Hamas blindsided Israel and prompted retaliatory strikes followed by a ground offensive into Gaza.

Although the government has also issued international debt in yen, euros and dollars through private placements via Wall Street banks such as Goldman Sachs Group Inc., it’s counting on the domestic market to absorb the bulk of its financing needs. The Finance Ministry has already sold 18.7 billion shekels of local bonds since Oct. 7, compared with a monthly average of just over 5 billion shekels through September.

Demand for its securities has stayed resilient enough to reach over six times the amount on offer at some recent auctions. Moody’s Investors Service estimates the government’s gross borrowing needs at around 10% of economic output this year, up from 5.7% in 2022.

Domestic interest rates have risen less in Israel than in many developed economies, making it relatively cheaper for the government to borrow at home. The yield on the nation’s 10-year shekel bond has inched up since the conflict began but closed on Wednesday down at 4.2% — lower than that of US Treasuries of similar maturity.

Thanks in part to unprecedented interventions by the central bank, the Israeli currency has completely recouped its losses after the war began and is now trading near the strongest against the dollar since August.

“If we look at the situation pre-war, the shekel was relatively weak and local capital markets were underperforming,” Rothenberg said. “Perhaps right now there is an interesting investment point in the Israeli economy.”

As the conflict forced the government to open the fiscal taps, it ran up a budget deficit in October that was more than seven times bigger than a year earlier, with the gap now at 2.6% of gross domestic product. Rothenberg said it’s reasonable to expect a cumulative budget shortfall of about 9% over the next two years.

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

“The financial costs are unlikely to be prohibitive for Israel. The country has $191 billion of foreign-exchange reserves, enough to fund the war for about two years. It could receive further assistance from the US. And it’s borrowing from financial markets to fill the gap. What’s going to end the war isn’t economics, but domestic or international pressure as well as developments on the battlefield.”

Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich has put forward an amended budget for the remainder of 2023 with a spending increase of 35 billion shekels that will be largely financed by debt. Israel will also have to make up for an estimated 15 billion shekels of lost revenues in 2023 and then next year re-stock a government tax compensation fund that was emptied of 18 billion shekels to pay for expenses after the war broke out.

Bond issuance at home accounts for over 80% of the total and officials don’t expect the ratio to change much, shielding Israel from volatile foreign investment flows.

Riskier Proposition

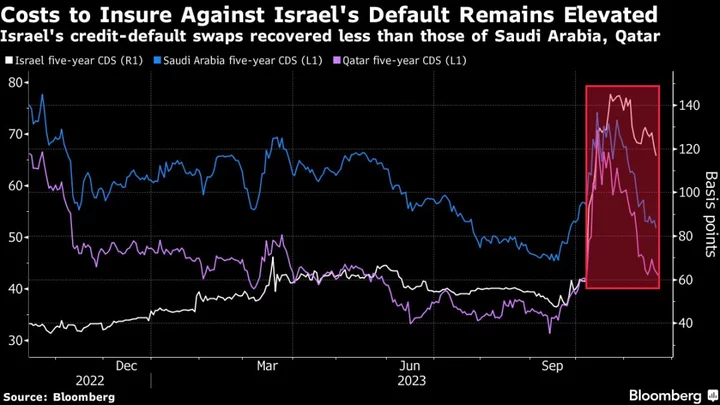

Israel faces a less welcoming market abroad. The cost to insure Israel’s sovereign bonds against a default has roughly doubled since the war began.

For the accountant general department, the unease has meant that it’s stepping up its outreach to rating agencies as well as foreign and local market makers by providing up-to-date data and explaining developments as they unfold. It’s also trying to facilitate inflows into the high-tech industry by speaking to potential investors and companies seeking capital.

“We are a country at war, but we have always had a very significant rebound after military operations and wars,” Rothenberg said.

Apart from relying on domestic debt since Oct. 7, the government also used a US-registered entity that’s separate but affiliated with the Finance Ministry to sell a monthly record of more than $1 billion of bonds bought by Israel’s supporters across the world.

It’s additionally borrowed abroad through privately negotiated deals, avoiding the scrutiny of public markets and raising a total of $5.4 billion since the war began.

Israel’s recent international bond placements were to large institutional investors “who really believe in Israel even in a state of war,” Rothenberg said. “This is a strong message they are sending.”

War Risks

The sudden strain on Israel’s finances has put the government in the spotlight of the three biggest rating companies, all of which lowered the outlook to negative in the weeks after the war began. But Israel has so far avoided what would be its first-ever downgrade.

In Rothenberg’s view, the decision might come down to Israel’s ability to hold back the budget deficit enough to support a decrease in the medium term of the ratio of debt to GDP — which is set to grow higher than its current level of about 60%.

While much of the focus is on debt, a fraught budget debate is unfolding in Israel over the fate of discretionary spending earmarked to the five parties comprising Benjamin Netanyahu’s government.

The reluctance to scrap or divert the funding has drawn controversy and, in the eyes of critics, threatens to undermine the government’s credibility.

Rothenberg said the special allotments should be “on the table” as Israel drafts a new economic plan for next year. “Priorities need to change as the world changed on Oct. 7,” he said.

--With assistance from Netty Ismail.