With splashy marketing campaigns and major donors like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, DKT International has become one of the world’s largest sellers of abortion pills, serving women from India to Mexico.

The Washington DC-based nonprofit says it provides high-quality medicines, condoms and other reproductive health products at affordable prices. But almost one-fifth of the 30 million products DKT distributes annually for abortions and postpartum hemorrhage prevention come from an Indian company with a record of making substandard medicine.

More than 30 samples of drugs made by Delhi-based Synokem Pharmaceuticals Ltd. — including generic abortion pills, an antibiotic and anti-seizure medicines — have failed quality tests conducted by Indian regulators and public health researchers since 2018, according to government records and data reviewed by Bloomberg News. The samples contained impurities, lacked the right amount of active ingredient or failed to meet other international standards designed to ensure that medicine is safe and effective, the records show.

Synokem abortion pills haven’t been linked to any deaths or serious injuries. But the company’s product failures, all detected after the drugs had been sold to pharmacies and other distributors, suggest its internal quality assurance system is not working, medical experts consulted about the data told Bloomberg.

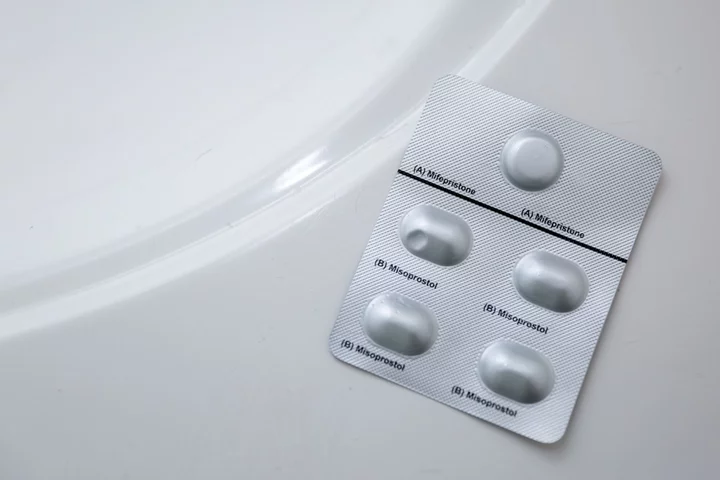

Since drugs like abortion medications are typically made by mixing ingredients in batches that can produce 100,000 to 1 million pills at a time, Synokem’s failed samples, including one with as little as 27% of the active ingredient, raise concerns about hundreds of thousands of other pills from the same batches. About one-third of those samples were abortion pills.

Some DKT abortion medication kits made by Synokem, part-owned by Boston-based private equity firm TA Associates, are now entering the US, even though they haven’t been approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The kits, which contain misoprostol and mifepristone, are being purchased through underground online pharmacies that have no affiliation with DKT, as court rulings and new laws restricting access to abortions force women to look elsewhere.

Unlike a typical nonprofit that relies primarily on donations, DKT depends on sales, which account for more than half of its $140 million annual revenue. Synokem’s cheaper drugs, which cost up to 40% less than more closely vetted alternatives, have helped DKT sell more pills, contributing to large bonuses earned by its executives.

Three public health experts told Bloomberg that they have called on DKT employees or the organization’s donors to encourage it to take quality more seriously and to work with manufacturers that meet international standards. One said they spoke directly with the Gates Foundation and asked it to intervene but got no meaningful response. They all asked that their names not be used because they’re still working in the industry.

The Gates Foundation, which has contributed more than $90 million to DKT over the past decade, is one of the nonprofit’s largest donors. It declined to comment on the use of Synokem products, noting in a statement that it does not fund DKT’s procurement of misoprostol and that “specific policies and processes are determined by individual organizations.” Neither Abhinav Arora, who runs Synokem, nor TA Associates responded to requests for comment.

Chris Purdy, DKT’s chief executive officer, said his organization takes quality seriously and he was not aware of any concerns public health experts had raised. He defended its relationship with Synokem, one that began about 20 years ago, when the nonprofit was looking to expand from condoms into prescription medicines.

“To suggest, at any level, that DKT accepts low quality, has somehow covered up less than acceptable quality misoprostol, or is motivated by money to allow low quality products to be sold, is incompatible” with the facts, Purdy said. He also said that DKT has not received any complaints from pharmacies, hospitals or other customers about the manufacturer’s products.

But Ndola Prata, a physician and professor at the University of California, Berkeley school of public health, said after Bloomberg shared its findings with her that DKT should switch to a supplier that can reliably meet quality standards. “There is no reason or logic to my view why they would stay with the manufacturer that has consistently had these issues,” said Prata, who has worked on reproductive health and access to misoprostol in developing countries.

DKT’s willingness to buy medicine from a company that has repeatedly failed quality tests highlights a key weakness in the world’s drug supply chain: There’s always a buyer lined up if the price is low enough, and those who make dangerous or ineffective drugs rarely face serious penalties. A Bloomberg investigation found similar dynamics were at the core of outbreaks of poisonous syrups meant to treat coughs, colds and nausea that were made in India and killed dozens of children around the world last year. The deaths and evidence of other contaminated drugs have put an unwelcome spotlight on India’s self-proclaimed role as “pharmacy of the world.”

If good manufacturing standards are followed, abortion pills are just as safe as many other commonly available drugs, clinical evidence shows. But the consequences of taking a poorly made pill — one that doesn’t have enough active ingredient, for example — can be dire.

In the most extreme cases, an insufficient dose can lead to an incomplete abortion. That’s particularly concerning if a person doesn’t have access to follow-up medical care. Since misoprostol is also used to prevent hemorrhaging after childbirth in low-income countries, taking a product that fails to stop bleeding can be fatal.

Medication now accounts for more than half of all abortions in the US. But those figures don’t include the increasing number of women who use unapproved suppliers as more states limit access to the drugs. Plan C, an abortion rights advocacy group, points women to more than a dozen websites that sell abortion medications. Several of those offer DKT’s A-Kare pills, made by Synokem. Plan C said it recently conducted testing of pills entering the US, including one brand that Synokem manufactured, and found no issues.

The number of patients harmed by substandard medicine is difficult to track and frequently goes undetected, particularly in places where health-care resources are limited. Women who have relied on the medicine for an abortion may also be reluctant to come forward. Even if they do, there are well-documented cases of drugs made by other manufacturers in which India’s regulators failed to thoroughly investigate.

Considering the stakes, many international aid organizations, including the United Nations Population Fund, routinely send inspectors to assess manufacturers’ practices. They also buy medicine whenever possible from manufacturers vetted by the World Health Organization or the strictest regulatory authorities such as the US FDA. Synokem’s facilities, like many of India’s roughly 10,000 drug factories, do not participate in this kind of vetting, which can be costly for manufacturers.

DKT hasn’t adopted some common safeguards to ensure medicine quality. The organization does not conduct inspections of Synokem’s facilities, according to Craig Darden, director of the nonprofit’s Mumbai-based program. Such inspections can help ensure good manufacturing practices are being followed. Instead, DKT said it relies on regular testing of the company’s products by an independent lab.

“All field offices have been directed to regularly test their products, with a special emphasis on misoprostol, given that product’s history,” said Purdy, noting that the medicine is susceptible to moisture and can degrade quickly if not properly handled. The testing program is the best risk-mitigation strategy and worth the expense, he said.

Yet many medicine-quality experts said testing alone is insufficient. For example, in India, the organization only tests Synokem’s products shortly after they’ve been manufactured, a practice that wouldn’t identify potential degradation over their shelf lives.

DKT’s Mumbai-based program also doesn’t check for impurities, according to tests commissioned by the nonprofit and reviewed by Bloomberg. Impurities can include substances that signal the active ingredient is degrading, as well as material that is unsafe for human consumption or has unknown effects. After Bloomberg raised the issue, DKT said it would now test Synokem’s products for impurities.

In 2021, the Concept Foundation, a Geneva-based nonprofit that supports access to quality-assured sexual and reproductive health medicines, found that eight Synokem samples it analyzed contained levels of impurities in excess of international standards. Those samples were purchased in several markets where Synokem’s products are sold, including India, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Cambodia and Uganda, according to the results of a study shared with Bloomberg that hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed. Two of those were A-Kare, the DKT-branded product that US consumers can buy through unregulated online sources that aren’t affiliated with the organization. The rest were other products sold by Synokem directly.

Part of DKT’s drive for lower prices stems from its unusual business model. The late Phil Harvey, a libertarian and owner of a sex-product retail business, founded DKT in 1989. He named the organization after his friend D.K. Tyagi, an Indian public health official and early champion of family planning in that country.

Instead of donating condoms and pills, DKT sells products at a low enough cost to make them widely accessible. It pioneered some of the first TV ads for medical abortion in India a decade ago and started a channel on OnlyFans, an online platform better known for porn, to sell its Prudence condom brand. Today it operates in more than 100 countries and estimates that last year it helped avert 10.8 million unwanted pregnancies, 9.3 million unsafe abortions and 33,000 maternal deaths.

DKT still relies on some donor support, including from the Gates Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. Both the Hewlett and Packard foundations said DKT provides safe, effective medicine. “We will continue to engage with DKT as they address any quality issues now and in the future,” said Carla Aguirre Piris, a spokesperson for the Hewlett Foundation.

But Purdy also has pushed the organization to expand and become less dependent on outside support since he became CEO in 2014. DKT operates more like a for-profit business: The more medicine it sells, the more money there is to fund other projects and bonuses. For Purdy that bonus amounted to more than $250,000 in 2021, according to the nonprofit’s most recent tax filing, bringing his total compensation that year to almost $1 million, a figure Purdy said included deferred income from prior years. That’s more than four times the compensation of the head of Doctors Without Borders USA, a nonprofit whose budget is four times larger.

Local country directors can also boost their compensation if they increase revenue or sales, according to an employee handbook and the nonprofit’s financial filings that describe DKT’s bonus system.

In its Mumbai-based program, a key market where DKT relies on Synokem’s inexpensive pills, growth from increased sales was lucrative for the program’s former director, Todd Callahan, who resigned in May. Under his watch, the program increased its sales in three years by more than 40%, selling 4.5 million abortion products in 2022. That helped make Callahan one of DKT’s highest-paid employees, earning $472,115 in total compensation in 2021, more than 25% of which came from his bonus, according to financial filings. Callahan didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“We have no concerns that DKT’s bonus structure would, in any way, allow for a compromise on product quality,” said Purdy. “Quality is the number one criterion for choosing our product manufacturing.”

Forty miles from Synokem’s two main manufacturing facilities, on a desolate road in the mountainous state of Uttarakhand, sits the office of a key regulator responsible for making sure the company’s products are safe. While Purdy said Indian regulators ensure Synokem is following good manufacturing practices, piles of folders stacked on the office floor suggest otherwise.

Synokem makes drugs for India’s domestic market and subcontracts for big generic pharmaceutical companies such as Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Cipla Ltd. and Macleods Pharmaceuticals Ltd., according to its website. It also exports to more than a dozen countries, records show. (Cipla declined to comment on Synokem’s quality. Sun and Macleods did not respond to requests for comment.)

Many countries rely on Indian regulators to police medicine exported to their hospitals and pharmacies. Those regulators are supposed to conduct inspections of manufacturing facilities and take action whenever they receive an alert that a sample picked up in the domestic market has failed a test. The harshest penalty under Indian law for producing substandard drugs is criminal prosecution, though it has rarely been used. A bill pending in parliament would allow manufacturers of some poor-quality drugs, such as those without enough active ingredient, to avoid jail time by paying a fine.

In each of three cases in which Synokem’s samples of misoprostol didn’t have enough active ingredient, including the one with only 27%, the Uttarakhand regulator suspended the company’s license to manufacture the product for three months.

Companies are supposed to identify the manufacturing lapses that caused problems and take steps to prevent them from reoccurring, but it’s unclear if that ever happened in these instances. The Uttarakhand regulator said it would be too difficult to locate documents showing the company’s response.

When a reporter arrived for a scheduled visit at the regulator’s office in May, officials also struggled to find inspection reports. After digging through a stack of files on the floor that the regulator gave Bloomberg access to, a reporter was able to find one. A staff member then went up to a room, which he said was so dusty he had to put on a surgical mask, and found a few more.

The reports showed that inspectors had identified only minor problems at Synokem’s facilities. All of the inspections had been preannounced, with the regulator alerting the company days in advance, said Sudhir Kumar, an assistant drugs controller.

While the inspection reports didn’t flag significant issues, at least 23 samples of Synokem’s drugs have failed quality tests since 2018, according to test results Bloomberg collected from six state and federal drug regulators in India. That’s likely an undercount because most of India’s 36 regional regulators don’t make such results public. One of the tests, involving a misoprostol sample collected at a hospital pharmacy in 2019, had so little active ingredient that a government-run hospital network warned all its members to stop using any medication from the entire batch, official records show.

The failed quality tests raise red flags for Prashant Yadav, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Center for Global Development who studies health-care supply chains. “Before a state agency detects a problem, an internal lab should have detected it,” Yadav said. These samples highlight that Synokem’s “manufacturing equipment, staff and competency are not up to the mark or that the integrity of the quality control tests done internally are definitely not up to the mark.”

Synokem has a close relationship with its watchdog. During the reporter’s visit, a Synokem employee walked into the room and asked what the reporter was doing there. The employee, Shailesh Sharma, who works in the company’s regulatory filings department, said he’d been alerted that a journalist was asking about the company as soon as she’d sent questions to the drug controller. The tenor of the meeting then changed, with one official saying the company might need to grant permission to view information about inspections and quality reports.

Kumar, who wasn’t in the office when the reporter visited, said he didn’t know who may have told Synokem about Bloomberg’s queries but that he and his colleagues maintain an independent relationship with the manufacturers they regulate.

Beyond issues flagged by India’s regulators, Purdy said his staff had identified a problem in East Africa, where Synokem was selling misoprostol to a customer unaffiliated with DKT in packaging that can result in the pill’s active ingredient degrading too quickly.

Purdy said he shared those concerns with country directors. The director in Myanmar, Debu Satapathy, who was relying on Synokem’s pills, said he raised the issue with the company, urging it to develop its own internal quality-assurance standards for packaging. The company didn’t make any promises, Satapathy said.

Synokem’s quality problems haven’t stopped it from attracting international interest. Earlier this year it received an investment from TA Associates, which installed several of its private equity executives on the manufacturer’s board. Among Synokem’s customers for abortion pills and postpartum hemorrhage prevention medication is Abacus Pharma, a company owned by the Carlyle Group that serves East Africa.

“Abacus is not aware of any batch failures of this product in our region,” the company said in a statement, noting that it relies on local regulators and quality testing conducted by the manufacturer before distributing products.

As Synokem continues to expand, and as DKT continues to rely on its products, more women run the risk of using substandard medicines.

“The international community has an obligation to make sure the medicines they’re supplying are only as good as the medicine they would give their own children,” said Paul Newton, head of the medicine quality research group at the University of Oxford. “To go for the bottom, the very least expensive, is inevitably — whether it is medicine or parts of bicycles — where you’re going to get into trouble.”

--With assistance from Shruti Mahajan.

(Updates with allegations of Synokem quality problems in East Africa.)