For Dhiraj Bajaj, the sudden twists and turns were unlike any he'd ever seen in his two decade investing career.

First, Dalian Wanda Group Co. indicated to bondholders -- including Bajaj -- that everything was fine. The $400 million it owed them would be paid in full. Days later, some creditors were warned that the company was, in fact, $200 million short, a bombshell that triggered a frantic sell-off in the debt.

And then, just as quickly, lenders were informed that there was indeed enough cash, sending the bonds surging once more.

Wanda would ultimately make the July debt payment. But Bajaj says the incident, and others like it, have left him deeply wary of investing in China going forward.

This is becoming an increasingly common refrain in the financial community. As dozens of debt-saddled property companies, including industry giant Country Garden Holdings Co., struggle to stave off defaults, international money managers say that it’s the weak — and many argue worsening — governance and disclosure practices that are putting them off mainland borrowers longer-term. That could lead to diminished access to financing and higher borrowing costs for years to come, experts warn, further hamstringing China’s already sputtering economy.

“There is a clear deterioration in terms of standards, and this will no longer be tolerated by the global investment community,” Bajaj said. “We are becoming less tolerant of many Chinese high-yield companies due to the lack of disclosure standards and direct, straightforward communication.”

Representatives for Wanda and Country Garden didn’t respond to multiple requests seeking comment.

Of course, China wasn’t exactly a shining example of good corporate governance to begin with. A number of companies have been plagued by hidden debt and accounting errors for years.

But with the nation’s junk-rated dollar bonds returning an average of over 9% annually between 2012 and 2020 — versus less than 7% for comparable US debt — money managers were, by-and-large, more than fine to look the other way.

Those gains are a distant memory now. China’s offshore junk bonds, most of which were issued by builders, have lost more than $127 billion in value since peaking just two and a half years ago, around the time Beijing was introducing the so-called three red lines to slow borrowing by developers.

The policies were intended to help curb years of excessive debt-fueled expansion by builders and property speculation by homebuyers. But they wound up tipping a record number of firms into default as refinancing costs surged, and leading to a string of restructurings.

Read More: China Junk Bonds Suffer Worst Slide of 2023 as Defaults Mount

Numerous global money managers said that while they were aware weak corporate governance was a risk factor when investing in China, standards, especially related to consistent communication with creditors, have been getting worse amid the mounting distress.

Country Garden, after missing the initial due date to make interest payments on two dollar bonds last month, then kept investors in the dark for weeks over whether it intended to pay the obligations before their grace periods expired (it ultimately paid the interest on Tuesday.) Further angering creditors was the fact that the company never clarified when the grace periods actually ended.

Just last month, developer China Aoyuan Group Ltd. submitted a regulatory filing in which it announced that three-quarters of holders of existing notes supported its restructuring agreement. The language led some to believe that the company had passed a key threshold to get the deal approved. But the backing only applied to holders of one particular security, leading to grumblings that the developer wasn’t providing a clear picture of investor support for the plan.

Last year, state-backed real estate firm Greenland Holdings Corp. rocked the market with a surprise request to delay repayment on one of its dollar bonds for a year, only to then pay back separate notes due a few months later.

And in 2021 Fantasia Holdings Group Co. shocked investors by defaulting on a dollar bond just weeks after assuring creditors that it wasn’t having liquidity issues, and days after repaying a privately placed note.

One investor who asked to not be identified speaking about a private matter reached out to Fantasia founder Zeng Jie via the messaging app WeChat after the company reneged on the debt asking about the non-payment. Zeng replied with a GIF of a cat on a litter box with the Chinese words “I’m pooping” superimposed over it.

Representatives from China Aoyuan, Greenland and Fantasia didn’t respond to requests for comment. Bloomberg also asked Fantasia representatives for a comment from Zeng, but none was provided. No contact details for Zeng were given, nor are they publicly available.

“Tapping credit markets is never a one-off deal. Even after distress events emerge or defaults happen, a company should not just run to seed,” said Lawrence Lu, a senior director of corporate ratings at S&P Global Ratings. “It’s time for Chinese issuers to change the mindset if they eventually want to get back to the capital market.”

‘Weak’ Governance

S&P evaluates corporations on the quality of their management and governance as part of its credit assessments. The rating company weighs governance factors including management culture, regulatory or legal infractions, consistency of communication and quality of financial reporting. Companies are assigned overall grades of strong, satisfactory, fair or weak.

Most mainland speculative-grade borrowers are scored as ‘weak,’ Lu said, amid a notable deterioration in performance in recent years that’s coincided with the property sector’s liquidity crunch.

“Communication with different stakeholders should be more frequent, transparent and issuers should give even-handed treatment to all investors,” Lu said. “There is much to do compared to global standards.”

That’s easier said than done, according to a former investors relations professional at a defaulted developer.

Companies’ cash positions are often in flux as they seek to complete projects, and money set aside for interest payments sometimes gets used to fund operations amid liquidity strains, said the person, who asked not to be identified because they didn’t want to jeopardize their future career prospects. Some developers would rather keep a low profile than make commitments to creditors that they can’t keep, the person added.

‘We Can’t Invest’

Nana Li, head of Sustainability and Stewardship for Asia-Pacific at Impax Asset Management Group Plc and a former China Research Director at the Asian Corporate Governance Association, says global bond buyers are already reassessing China credit allocations.

“Foreign money managers still have willingness to invest in China, but how much we invest is in flux,” Li said. “We’re facing a market that’s full of uncertainty, and combined with a lack of transparency, it’s harder to make forecasts. Without forecasts, we can’t invest.”

That could have significant repercussions for companies seeking financing, according to Tommy Wu, a senior economist at Commerzbank AG.

“All companies would have to turn to onshore funding, further pressuring local banks and authorities, who are already busy clearing mounting debts issues,” Wu said. “It will also push up funding costs of Chinese companies and erode their profitability, dampening their willingness to expand business, or even leading to layoffs, all of which would further weigh on the Chinese economy.”

The world’s second-largest economy hardly needs additional challenges. A private survey of China’s services sector showed activity expanded at the slowest rate this year in August, as the outlook darkened and the property turmoil held people back from spending.

Beijing is trying to revive confidence after the latest data showed home sales slumped for a third straight month, adding to deflation pressure. Late last week, China moved to allow its largest cities to cut down payments for homebuyers, and have also encouraged lenders to lower rates on existing mortgages.

Speculative bets that authorities may widen support further sent some ailing developers surging by the most on record Wednesday.

Read More: Why China Is Avoiding Using ‘Bazooka’ to Spur Economy: QuickTake

Lombard Odier’s Bajaj says it falls on Chinese regulators to step up efforts to better ensure high corporate governance standards.

This includes Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission as well as the People’s Bank of China, the National Development and Reform Commission and the China Securities Regulatory Commission.

A representative for the SFC said incidents such as selective disclosure by companies of market moving information could fall under its market abuse provisions and would be taken “very seriously” by the regulatory body.

The PBOC, NDRC and CSRC didn’t respond to requests seeking comment.

“Something has to be done by regulators in China,” Bajaj said. “If not, I’m afraid that the global investor base is going to shrink for Chinese company bonds.”

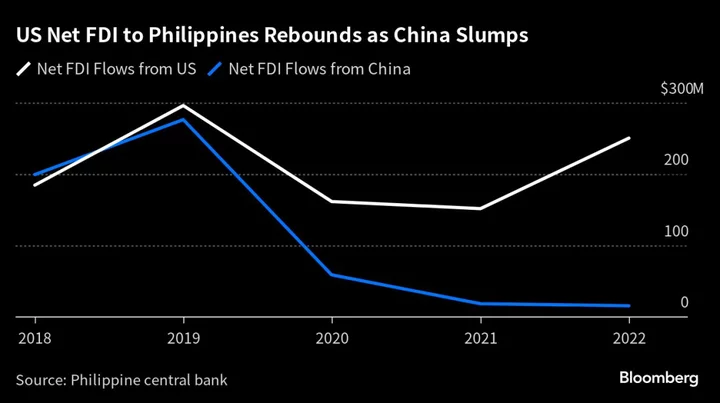

That would be another hit to an economy already struggling to lure foreign investors. Just last week US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo said American businesses consider China increasingly “ uninvestable,” even as Beijing has in recent months promised to treat international investors better.

For Willem Glorie, a portfolio manager at LGT Capital Partners who held Wanda bonds, it will take more than a charm offensive to win back his trust.

He says it wasn’t the conflicting messaging or wild price swings that he found most troubling about the July incident. The more frustrating part for him was how some investors were told of the company’s plans before others.

It’s “not disseminated in an open way to all investors at the same time,” said Glorie. “They’d mention to some investors one thing and the next day if there’s a development, they’d mention something else. It cannot be that investors have to chat with companies everyday to get what the latest issue is.”

--With assistance from Lulu Yilun Chen, Emma Dong, April Ma, Alice Huang and Dorothy Ma.