The Bank of England does not need to raise interest rates further to bear down on inflation because policy is already restrictive enough, Chief Economist Huw Pill said.

Addressing the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, Pill said: “Having established monetary policy in restrictive territory it is not the case that we need to raise rates in order to bear down on inflation. Sustaining rates at their current level will continue to bear down inflation.”

“It is that maintaining of the restrictive stance that is key to achieving the inflation target.”

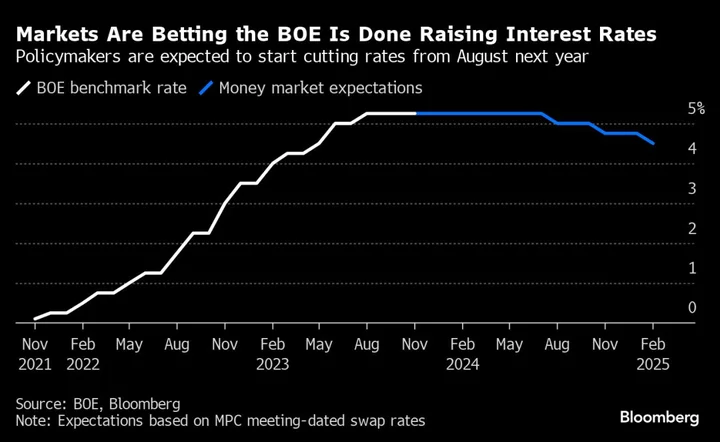

The BOE last week held rates for the second time running at 5.25% and downgraded its growth forecast, prompting markets to remove any further rate hikes from their expected path.

Traders are now betting that the next move in rates will be lower. Markets are pricing in three quarter-point rate cuts, starting in August next year.

BOE Governor Andrew Bailey has pushed back against talk of rate cuts, saying it is much too early to consider them.

Pill said rate hikes are working. Inflation has dropped to 6.7% from double digits earlier this year. Official consumer prices data next week are expected to show inflation dropping below 5%.

“Inflation returning to target is not entirely as a consequence of external events,” he said. “Yes, we are benefitting from global developments but we are also acting through monetary tightening. That tightening of monetary policy is bearing down on inflation and contributing to this decline.”

However, he cautioned that underlying domestic price growth remains too strong. He warned that inflation is proving more persistent than thought, particularly in services where he has not seen “a decisive turning point.”

“A key risk for us is that there is some self-sustaining momentum in that services component, in that domestically driven component,” he said. Wages are also proving stickier than expected, he added.

“Wage growth will take longer to get back to levels that are more consistent with the 2% inflation target” than previous models suggest, so there will be more persistence, he said.

“We are becoming more confident that we can bring inflation to target but we will keep interest rates at their current level for an extended period.”

The economy has slowed faster than the BOE forecast in August, with the bank now expecting zero growth over the whole of next year.

That weakness would be expected to bring down inflation but Pill said the growth capacity of the economy has also shrunk. As a result, even slow growth can lead to overheating in prices.

How much economic harm the BOE will have to inflict will depend in a large part on the performance of the labor market, he said. “Implicit... is do we need to generate more unemployment to bear down and restrain pay growth and domestically generated inflation?” Pill asked.

Ideally, people who dropped out of work since the pandemic will rejoin the labor force, reducing the mismatch between demand for staff and worker shortages, he said.

“The better the labor market behaves in matching workers with jobs, the better for us … we don’t need to restrain demand as much as we would otherwise need to do.”

He pointed out that workforce participation has collapsed. “There is a restraint on the supply of labor, that will tend to create pressures on wages,” he said, adding that the “inactive pool needs to be mobilized in some way” to ease those worker shortages.

The number of inactive people who neither have nor want a job is still around 400,000 higher than before the pandemic, with much of the increase down to long-term ill health.

(Adds comments from Pill, chart)