It became a symbol of corporate Japan’s slide toward mediocrity when it got into difficulties during the global financial crisis and posted the biggest loss ever by a Japanese manufacturer.

But then Hitachi Ltd. changed.

The old-school conglomerate, which was involved in everything from nuclear power to consumer electronics, revamped its governance, shrank its empire to focus on growth and evolved into a more global enterprise.

The transformation made Hitachi an investor darling as other iconic Japanese groups hit harder times. Its shares have surged more than eightfold from a 2009 low, and rose to their highest on record this week after climbing more than 30% this year.

Hitachi’s metamorphosis belies the argument that the bastions of Japan Inc. are set forever in their ways. It may offer a blueprint for other aging behemoths as the country’s population shrinks and forces them to abandon any insular tendencies and become citizens of the world.

And as the stock market hits a 33-year high, inflation finally takes hold and even Warren Buffett talks up Japan, it’s reassuring some investors that the reasons touted for the optimism — such as an overhaul of how companies are run — are more than just hype.

“Hitachi has been a fascinating ride, seeing this wild, sprawling organization steadily concentrate itself and refine itself,” said Sam Perry, a London-based portfolio manager at Pictet Asset Management, who manages $590 million. “It has got rid of an awful lot of assets. Hitachi’s pretty much the poster child of the corporate governance change that we’ve seen in Japan.”

Keiji Kojima, Hitachi’s president, is unequivocal about how it happened. A predecessor, Takashi Kawamura, was picked to turn the company around in 2009. Kawamura added more independent directors — a rare move in Japan. By 2012, outsiders accounted for most of the board. Today, 9 of the 12 are outside directors, and 5 aren’t Japanese.

“The board has become so global,” Kojima, who has run the company since 2022, said in an interview. “Without it, structural reform would have been impossible,” he said. At board meetings, “there’s no such thing as reading the room. There’s no compromise, no delaying things.”

People outside Japan might remember Hitachi for its televisions, PCs or even its sponsorship of Liverpool Football Club in the late 1970s and early 1980s. But there was much more. The company founded in 1910 by an electrical engineer also developed nuclear reactors, made air conditioners and created the first cars for the Shinkansen bullet train, to name a few. Until the late 2000s, it was Japan’s biggest private-sector employer for many years.

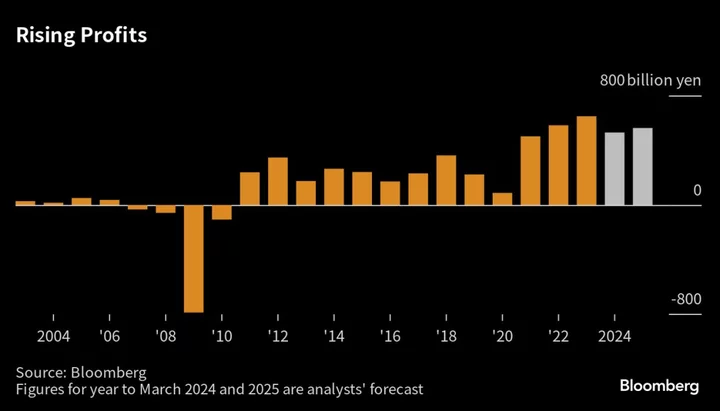

Then, during the financial crisis, things went wrong. The company posted a ¥787 billion ($8 billion based on the exchange rate then) net loss for the year ended March 2009, the biggest ever at the time for a Japanese manufacturer, due to chip business losses and plunging product demand. Kawamura took over in April 2009 with a mission to turn things around.

“I thought we could go bankrupt,” the 83-year-old former president said in an interview. “I got rid of hardware businesses that have little to do with digitalization. I met a lot of resistance. I almost died from it, with lots of guys coming up and asking ‘Why the hell are you abandoning the business I started?’”

Kawamura made the board more independent and international, a policy continued by his three successors. It’s difficult to overstate how unusual this was. Even today, just 12% of companies listed on the Tokyo’s Stock Exchange’s prime market have a majority of outsiders on their boards, according to bourse operator Japan Exchange Group Inc. Foreign directors are rarer, making up only 5% of Nikkei 225 company boards, compared with 36% in the UK and France, according to consulting firm Spencer Stuart.

At the same time, Kawamura started to overhaul the company.

Hitachi exited loss-making businesses such as semiconductors, hard drives and television. It sold many subsidiaries, including its metals, chemicals and cable-making units. In 2009, the company had 22 units that traded on the stock exchange, subjecting it to criticism from analysts who argued parent-child listings create hurt minority shareholders. Today, it has no listed subsidiaries.

Hitachi also narrowed its focus to growth areas. One is green energy, which includes railway systems and power grids. Another is digitalization, such as systems for banks and governments.

“Hitachi has definitely gone the pathway of really reshaping its business portfolio,” said Damian Thong, an analyst at Macquarie in Tokyo. “They basically spent the last 10 years refocusing on two key areas.”

In later years, the company made some big foreign acquisitions to strengthen those areas. It bought the power grid unit of Zurich-based ABB Ltd. in 2020, and US software developer GlobalLogic Inc. in 2021 for $8.5 billion, one of its biggest deals ever.

And while Hitachi still has legacy businesses ranging from managing nuclear power plants to selling clothing irons, its priority areas have boosted profit.

Hitachi was able to reinvent itself because it has an overarching strategy, according to Katsuhiro Sato, professor of strategy and finance at Waseda Business School in Tokyo and a former McKinsey & Co. partner. It was one of the first Japanese businesses to think this way and remains one of the few that do, he said.

“When Japanese companies create medium-term business plans, what they often do is ask each business unit to come up with their business plans, staple them together and present them as a corporate strategy,” Sato said. “When management changes and a new leader comes in from a different business unit, they often speak in a different language.”

Hitachi calls its strategy Lumada, coined from the words “illuminate” and “data.” It involves not just selling a product, but designing, building, running and maintaining it.

Hitachi gives the example of a system it introduced in Genoa, Italy, to allow people to enter the public transport system hands-free and without the use of gates. It also points to an automated ordering method developed for Japanese functional clothing and sportswear retailer Workman Co.

“Hitachi doesn’t really have any area where it really stands out,” said Masakazu Takeda, a portfolio manager at Sparx Asia Investment Advisors Ltd. who first invested in the firm in 2021 and now considers it a top pick. “But it’s unique in that it has all this expertise under the one roof,” including manufacturing, information technology and systems operation, he said.

Hitachi posted record net income of ¥649 billion in the year ended March. Sales were ¥10.9 trillion, less than a peak of ¥11.2 trillion in the year ended March 2008.

And the firm is becoming more global. Most of its revenue came from overseas last fiscal year, and more than half its 322,500 staff work outside Japan.

Hitachi shares have risen more than eightfold from a December 2009 low, compared with a gain of about 160% for the country’s benchmark equity index. This week, the company passed an all-time high reached in 1988.

“The conglomerate discount on Hitachi’s shares has disappeared,” said Yasuo Sakuma, chief investment officer of Libra Investments. “The company has made a great transformation,” he said. “Hitachi can become a role model for other Japanese companies.”

Few would dispute that some would benefit.

The obvious example may be Hitachi’s old rival Toshiba Corp., which is selling itself to a consortium led by a Japanese private equity firm after scandals and mismanagement plunged it into difficulties. Today, the two are no longer of the same scale. Hitachi has a market value of $61.8 billion, more than four times that of Toshiba.

And Toshiba is far from alone. While Hitachi trades at 1.7 times book value, about 45% of companies in the Topix are still valued at less than the price of their assets, suggesting a level of investor skepticism that’s prompting the Tokyo Stock Exchange to encourage them to undergo similar transformations as Hitachi.

Read More: Hedge Funds Pushing for Japan Returns Get Help From Tokyo Bourse

Morgan Stanley MUFG Securities Co. says Hitachi’s stock valuation is “difficult to justify.” The company hasn’t fundamentally improved operations in existing areas and complexity remains in the business structure, analysts led by Masatoshi Terashi wrote in a note in July.

Another challenge Hitachi faces is managing its now global organization. Kawamura, the architect of its reinvention, says the group may need to move its head office overseas.

“If you keep the headquarters in Tokyo, the company may not grow that much,” he said.

Kojima, the current president, doesn’t go that far. But he says Hitachi should become more decentralized.

Kojima says other Japanese executives ask him about Hitachi’s governance overhaul, and he tells them a strong board is key. He says the board continues to stress Hitachi’s workers in Japan must resist old ways, such as believing it’s OK not to grow.

“The most important thing is to be where growth is,” Kojima said. “The old model of controlling the world from one place doesn’t really fit the solution business.”

--With assistance from Tsuyoshi Inajima.

(Corrects company name in first graphic.)