In the vast woodlands that surround the Bavarian city of Augsburg, Eva Ritter looks across piles upon piles of dead spruce trees with concern. Just days previously, they helped absorb some of the emissions that stoke climate change, but now they’re a sign of how difficult the crisis is to fight.

After years of drought weakened their defenses, an infestation of bark beetles tore through the insides of the trees this summer, forcing Ritter and her team of foresters to have them chopped down and carted away before the damage multiplies. Over the course of a year, a single infested tree can affect 400 others.

Compared to the wildfires that have gripped headlines in recent months, beetles are a less obvious source of devastation for Europe’s forests. Yet they form part of a growing battery of threats that undermine the continent’s efforts to fight climate change.

“The heart of any forester bleeds witnessing this scale of destruction,” said Ritter, a 34-year-old who oversees 7,700 hectares of woodlands near Augsburg — home to some of Europe’s highest timber stocks. “In our business, climate change is part of everyday life.”

For the European Union to achieve its goal of becoming climate neutral by 2050, it needs not only to reduce emissions, but also increase carbon dioxide removals from the atmosphere. While the bloc plans to plant 3 billion additional trees by 2030 to help that effort, keeping the old ones alive has proved challenging.

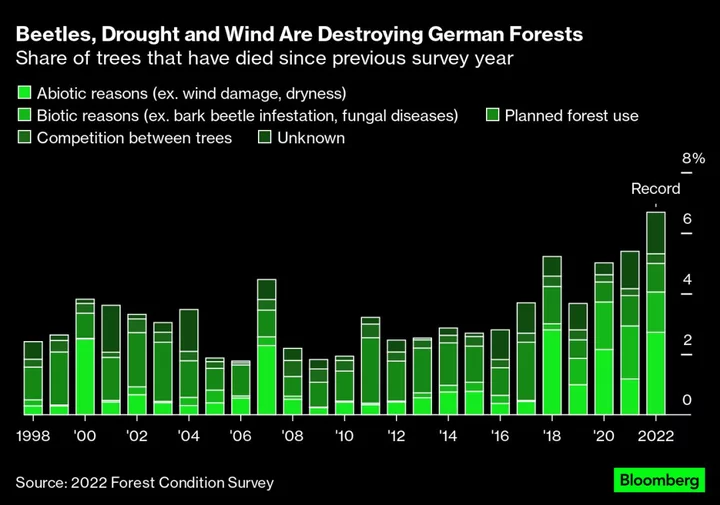

Devastating wildfires in Greece this summer have destroyed an area much larger than New York City and taken at least 25 lives. In Germany, bark beetles, drought and storms led to record rates of forest destruction last year.

In Austria, damage caused by the bark beetle almost doubled in 2022, and outbreaks in the Czech Republic since 2018 have been so severe that forests haven’t been reducing carbon emissions, but increasing them in part because of rotting trees.

“The fires get a lot of attention in the media — for good reasons — but the burned areas in Europe are not that enormous,” said Gert-Jan Nabuurs, professor of European forest resources at Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands. “Central European droughts and bark beetle infestations are causing massive mortality. That’s certainly the main issue.”

In Germany, even weeks of rain haven’t quenched the forest’s thirst. That’s because summer precipitation is absorbed relatively quickly, or evaporates. Wet and snowy winters are important for sustained soil moisture, but those have become more rare. Since 2018, swaths of the country have been characterized by drought, data by the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research show.

“For a tree, even a single dry period is like a stroke,” said Ritter as she surveys the damage in Augsburg’s forests. “It takes three to five years to recover.”

The weakened state of the trees makes it easier for bark beetles to bore holes and lays eggs under the bark. The larvae then feed on the bark layer, which is vital for transporting nutrients. If a tree is infested, it needs to be felled within a few weeks and taken away to prevent the insects from spreading.

Bark beetles are particularly fond of spruce trees. The evergreens wouldn’t normally be so widespread in Germany, but were cultivated widely after World War II when reconstruction required timber resources. They now make up a quarter of its woodlands, which in turn cover about a third of the land. The trees require a lot of water due to shallow roots, which makes them prone to wind and storm damage while also drying out the soil for other vegetation.

“Now we have to deal with these forests and need to make them climate-ready,” said Andreas Bolte, director of forest ecosystems at the Thünen Institute, which conducts research in economics, ecology and technology and advises policymakers. “Forests have so many protective functions — water filtering, climate dampening and erosion control — these are all properties that will become more important.”

Efforts have been underway in Germany for the past two to three decades to build up more natural mixed forests that include different conifers and deciduous trees to boost resilience. But progress has been slow and complicated by several factors, including the fact that about half of German woodlands are privately owned — also common in other parts of western and northern Europe.

About 65,000 individuals in Germany inherit a forest each year — many possibly lacking the skills, experience and resources to manage damage and outbreaks. On top of that, a 2018 survey by the Thünen Institute showed that while almost all private owners saw an important role for forests in climate protection, nearly 40% prioritized economic uses over preservation.

Forests have long been a source of raw materials, and biomass — which includes burning wood — continues to be the main source of renewable energy in the EU, with a share of almost 60%. While trees can regrow, critics argue that this destroys a limited resource and raises emissions.

“We still need a certain amount of energy production from wood, but it’s important not to burn wood that would actually be suitable” for more valuable uses, said Bolte from the Thünen Institute.

The carbon-absorbing properties of forests are expected to worsen across much of Europe this decade — mainly due to the increasing damage and timber harvesting. But Michael Köhl, a professor of world forestry at the University of Hamburg, argues that forests shouldn’t be seen only as a “passive” sink. Since wood can be used as an alternative to more emissions-intensive materials like cement, they can help lower pollution through substitution.

Future-proofing forests isn’t an exact science, and there are different views on how to do it. Some argue the forest should be left alone, with natural destruction eventually allowing a return of biodiversity. Others say it’s important to actively support reforestation, for instance, by cultivating trees better suited for warmer climates.

“We would need trees that can cope in a refrigerator as well as in an oven,” Ritter said. In her forest in Augsburg, she has experimented with varieties from milder parts of Germany, but also with trees that are native to Turkey and the Balkans, such as the Turkish hazel.

Forestry work used to be relatively easy to plan but that’s changed, according to Daniel Kugler, who manages one of the forest sections near Augsburg.

“For the past few years we have been permanently in crisis mode,” he said standing at a clearing where a storm nearly sent a tree crashing into a water pump a few days earlier.