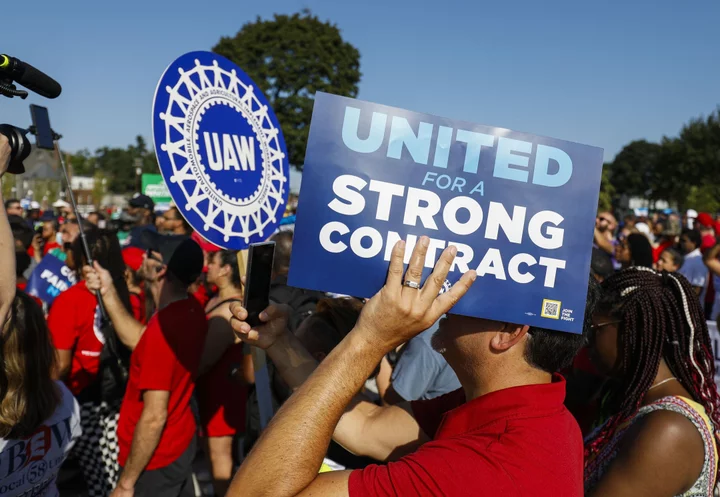

Workers in the US are getting record-breaking wage hikes this year thanks to strategic strikes and stunning contract wins. The result is a boost in middle-income wages and a shift in the balance of power between companies and their employees.

Even before the United Auto Workers reached historic contract deals with carmakers, unions across the country had already won their members 6.6% raises on average in 2023 — the biggest bump in more than three decades, according to an analysis by Bloomberg Law.

The recent victories mark a potential turning point for the country’s labor movement, which has seen union ranks and power dwindle for decades. Emboldened by towering corporate profits, UPS drivers, Hollywood writers, autoworkers and others made ambitious demands many considered unattainable. Using new tactics — and taking advantage of a tight labor market and shifting views on organized labor — one-by-one, they won big.

“We are seeing an incredible moment of worker power,” Acting US Labor Secretary Julie Su said in an interview. “We said that essential workers matter, and now workers are saying, ‘Let's really figure out what that looks like.’”

These contracts only cover a tiny slice of the US labor market, but the wage gains could also have spillover effects to other workers. FedEx executives privately worried the pay bumps secured in the most recent UPS contract, particularly for part-time package handlers, would make it more difficult to recruit.

Read more: How the UAW Won Raises and Bonuses by Striking for Six Weeks

They also don’t come without risks. Companies say they can’t stay competitive with higher labor costs, while others have signaled that they will reduce headcount or change where and how they do business. Automakers in fierce competition to dominate the electric-vehicle market have already suggested they might move some factories to Mexico, Canada and other overseas locations. Netflix and other streamers are revving up production outside of the US so they’re less reliant on Hollywood.

Record Breaking Gains

The United Auto Workers scored some of the biggest raises among US workers this year. Tentative deals reached over the last week with Ford Motor Co., General Motors Co. and Stellantis NV include a 25% hourly wage increase over four-plus years, with an 11% bump in the first year, the biggest jump the UAW has seen this century.

Union president Shawn Fain took an unconventional approach. He targeted a plant from each car company and then incrementally expanded the strike based on what was happening at the bargaining table. That allowed him to hit lucrative factories without burning through the union’s strike fund. Ultimately, his strategy secured hefty victories, including more generous 401(k) retirement benefits, cost-of-living pay increases and the elimination of lower tiers of pay.“It is ground-breaking, if not earth-shattering,” said Robert Reich, former US secretary of labor, of the UAW’s agreement with automakers.

Wages have stagnated, even as productivity has risen substantially, Reich said in an interview with Bloomberg Television. “That has generated a very strong, built-up desire on the part of workers — and really on the part of the public in general — to increase the wages of these people.”

This wave of union wins started at the tail end of last year, when more than 100,000 railroad workers threatened to walk off the job for the first time in decades. A work stoppage would have halted shipments for businesses across the country, costing the US economy billions and possibly tipping it into recession.

The strike was averted when Congress forced the unions to accept an agreement, even as some workers voted to reject the contract to get more guaranteed sick leave. Still, the threat alone was powerful: Workers ended up with unprecedented gains, including a 24% wage increase plus a $5,000 bonus over five years and new scheduling rules that guarantee uninterrupted time off.

Since then, thousands of US workers have negotiated record-making deals using new playbooks. This summer, television and movie writers got guarantees for bigger wage boosts than they’ve seen this century, in part by using social media to marshal public support and encourage members to hold the line.

“The workers are p---ed and that’s why we’re winning,” said Adam Conover, a comedian and member of the negotiating committee for the Writers Guild of America. “It’s a massive victory.”

It was a similar story at UPS, where workers will get a 10% pay increase in the first year of the contract. The Teamsters union’s new president, Sean O’Brien, did things differently than his predecessor. He started talks six months before the contract expired, instead of a year out. He also spent time crisscrossing the country to build support for a potential strike and made it clear to UPS that he wouldn’t delay a strike if negotiations slid past the Aug. 1 deadline.

At Kaiser Permanente, health-care workers staged the biggest walkout in the sector ever, with 75,000 joining a three-day strike in early October. The group threatened a longer stoppage if the health system didn’t agree to address staffing shortages. Around 10 days later, the union won a deal with pay bumps bigger than anytime in the last two decades.

‘Great Momentum’

Labor leaders had a variety of things working in their favor at the bargaining table, some of which may not endure. Tighter labor markets that now look to be cooling gave employees more leverage — with or without a union — to secure raises. There’s also been a sentiment shift. Coming out of the pandemic, many of these jobs were deemed “essential” but weren’t valued as such, despite companies reporting record profits and stock gains that led to huge CEO payouts.

Public approval for US unions last year was up to a 57-year high, though has since dipped slightly. Solid majorities of Americans polled by Gallup said they sided with screen writers, actors and auto workers in their disputes.

“I would go to comedy clubs all across the country and I would open by saying, ‘Hey, I'm on strike right now,’ and the crowd would give me literally a 45-second ovation,” Conover said. “People in the middle of the country stopped me on the street and said, ‘Hey, good luck on the strike.”

US labor is no longer in a “defensive mode,” said Nelson Lichtenstein, the director of the University of California Santa Barbara’s Center for the Study of Work, Labor and Democracy. Until recently, it was easier for business leaders to dismiss organized labor as greedy or corrupt. “They don’t have a language right now to oppose it,” said Lichtenstein. “Things like, ‘oh be realistic,’ fall on deaf ears.”

Similar forces are leading to record strike activity in the UK, where more working days have been lost to walkouts in the last year than in any time since the 1980s. In France, more than a million people took to the streets in January to protest President Emmanuel Macron’s pension reforms.

Read more: Tesla and Anti-Union Elon Musk Make Enticing Targets for UAW's Next Push

Labor leaders have publicly said they hope to use the wins to grow their ranks. Unionized workers have historically made 10% to 20% more and get better benefits than those who aren’t. Yet, only 6% of private sector workers in the US belong to a union, down from 11% thirty years ago — a far smaller share than in Europe or Canada, where around a quarter of the workforce is unionized.

The Teamsters’ O’Brien told Bloomberg News that he expects to “be successful” at Amazon in the next four or five years. He’s is also using an approach similar to the one he took at UPS in current contract negotiations for 5,000 production workers at 12 US Anheuser-Busch breweries.

“We’ve got some great momentum,” O’Brien said.

--With assistance from Robert Combs, Thomas Black and Alexandre Tanzi.

(Updates with quotes from Robert Reich in the 9th and 10th paragraphs.)

Author: Josh Eidelson, Laura Bejder Jensen and Jo Constantz