Ukraine needs its women refugees to come home, and soon.

Almost a year and a half into President Vladimir Putin’s faltering invasion, the cost of resistance for Russia’s neighbor has been devastating. Unless Ukraine’s six million-plus refugees return, some of that damage will be permanent.

Most men age 18-60 aren’t allowed to leave the country, which explains why 68% of Ukrainian refugees are women, with an even greater gender disparity among adults. Failure to persuade any of the 2.8 million working-age women to return would cost Ukraine 10% of its annual pre-war gross domestic product, according to Alexander Isakov of Bloomberg Economics.

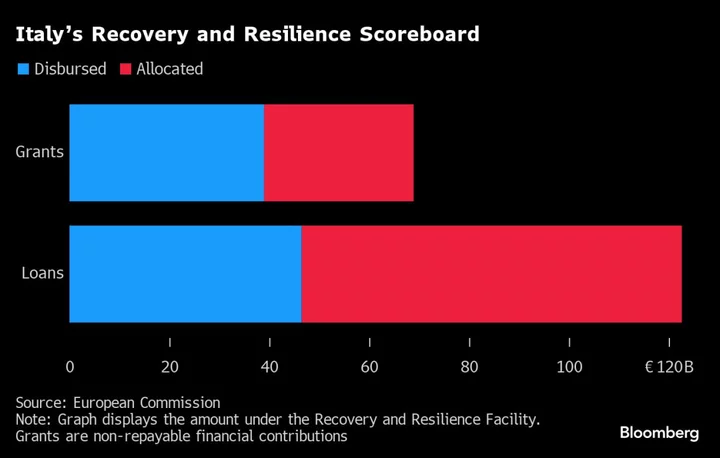

That’s $20 billion a year in a worst-case scenario that would easily outweigh the European Union’s proposed four-year aid package for Ukraine, worth an annual €12.5 billion ($13.9 billion).

“For me personally, victory is when Ukrainian families unite in Ukraine, not abroad,” Deputy Economy Minister Tetyana Berezhna said in an interview in her office in Kyiv, part of a government zone that’s surrounded by checkpoints. “So the most important task now for Ukraine, for the Ukrainian government, is to make everything possible so that women with children come back to their husbands and unite in Ukraine.”

Even before the war, Ukraine’s weakest economic link was its demography, with a fertility rate of just 1.2, among the worst in Europe. Tens of thousands of killed soldiers and civilians, and even larger numbers too injured or traumatized for employment, further reduce the number of consumers and members of the workforce that are indispensable to recovery.

The government has ambitious plans for post-war reconstruction that would double the economy’s size by 2032, but the economy ministry says Ukraine is 4.5 million short of the number of workers and entrepreneurs needed to achieve that goal. It aims to plug the gap with a mix of returning refugees — 60% of whom have degrees — and foreign talent.

To that end, it’s working on incentives to bring women back into the work force, including a new labor law, attempts to narrow the gender pay gap, and grants to help the spouses of those fighting at the front start businesses.

Taken together, Ukraine’s refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs) amount to almost a third of the 37.3 million population the government said was living on territory it controlled before Putin launched his all-out invasion. And while some of those displaced inside the country may still be able to contribute to Ukraine’s economy, those now living abroad are beginning to find work, pay tax and boost output elsewhere.

“Only people make the GDP of an economy,” Oleg Gorokhovsky, chief executive of Monobank, a mobile-only bank service provider, said at his office in Kyiv. “I’m afraid that a lot of intelligent and smart people, young people, especially women, leave Ukraine.”

Women, he says, have a disproportionate impact on consumer demand because they tend to be the primary decision makers when it comes to household purchases. “Without them it will be super hard,” he added.

Yes, many refugees are likely to return over time. Yet there are few guarantees as to how many, and persuading them to come back becomes more difficult the longer the war goes on: It took almost a decade after the end of Europe’s last war, in Bosnia in the 1990s, for half the conflict’s 2 million refugees and IDPs to return home, according to the UNHCR.

According to Isakov’s calculations, a similar outcome for Ukraine in which half of all refugees return would cost the economy $10 billion per year. That’s 5% of GDP, after accounting for some husbands and families moving to join those women who decide to stay abroad.

At least as important as lost demand is the loss of labor. So much so, says Oleksandr Zholud, the central bank’s chief analyst for monetary and economic policy, that Ukraine is looking for ways of filling the coming deficit beyond returnees. Whereas questions of immigration are often problematic elsewhere, “in Ukraine we already have a debate under way about the need for new foreign immigrants after the war,” he said. Zholud was speaking in a personal capacity and not on behalf of the central bank.

Before that point, however, the focus is on persuading refugees to return to places like Mykolaiv.

When Denmark agreed to lead a wartime reconstruction program in the port, Ambassador Ole Egberg Mikkelsen knew he’d be helping to restore water and energy infrastructure to make the city livable again. He didn’t expect to be building bomb shelters for kids.

The project was agreed on July 3 to restore as many as 16 damaged schools, adding shelters where appropriate, “because families with children said they wouldn’t come back to a city so close to the front lines without them,” said Mikkelsen.

Many people have returned, reflecting the fact that numbers aren’t static but represent a snapshot of constant flows. The city’s local government has done a lot to make the prospect more attractive: A fleet of new buses is replacing those destroyed in the war; bus stops now have concrete bunkers adjacent where people can shelter during alarms; there’s heat and water in the pipes, even if it isn’t potable.

That isn’t yet enough to entice Daria Chestina to come back from Brazil with her nine-year-old daughter, Varvara.

Varvara had lost touch with her friends after fleeing the shelling and tanks rumbling through Mykolaiv. By the time they reached Curitiba, some 400 km (248 miles) south of Sao Paulo, she’d become reclusive, angry and unwilling to eat.

Once there, Chestina, the commercial manager for a large grain terminal in Mykolaiv’s port before the war, quickly found work at a Brazil-based commodities consultancy. And Varvara is happy at her international school, being taught in Portuguese and English.

Chestina’s mother has returned to Mykolaiv already, to reopen her bakery, and she herself visited in May. But school bomb shelters aren’t enough to remove the threat of barrages of cruise missiles for Chestina, who already had to flee once before, from the northeastern city of Luhansk in 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and stoked an armed insurgency in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region.

“If I didn’t have my daughter, I would be back in Ukraine already,” said Chestina, 31, who worries that younger people like her who speak a foreign language and have globally employable skills will never return, hollowing out a critical resource for building a new Ukraine. If people don’t return, she said, then “why do we do this war?”

Some younger residents are coming back to Mykolaiv, still just 70 km from the front lines, where the reconstruction projects create a sense of progress, according to Mykola Kapatsyna, who owns Roadstead Terminal “Concord” LLC, a shipping services company in the still shuttered port. Kapatsyna, who is working with the Danish government, says four kindergartens with bomb shelters recently opened their doors, and they’re packed.

Even so, a disproportionate number of returnees are older or retired, and it’s hard for the young to find decent work, according to Kapatsyna. He reckons it’ll take a good two years without interference from the Russians to get utilities and services back to normal, and that for now people will just have to decide for themselves if that’s enough to return. “We don’t have any other solution,” said Kapatsyna. “Not even a huge budget can solve the problem.”

Valeriya Lyulko was partner in a business with two others in Kyiv before last year, helping foreign companies including Paramount Global and Hasbro Inc. to license products in Ukraine. One business partner went to fight, one stayed in Ukraine to keep the company afloat, and Lyulko left to take her son, now 12, to safety. Paramount arranged a job for her in Germany.

While Germans have been very kind, the country is not Lyulko’s dream destination. She’s still getting used to filling out paper forms and having to check her mailbox for post, after Ukraine’s hyper-digitalized government services. And she’s not a fan of Germany’s stratified school system. Even so, she’s trying to convert her refugee document, which expires next year, into a more permanent work visa.

“People who figured out the work situation in Germany, in the Netherlands, in the UK or, like, in any European country, they more or less are planning to stay where they are at this point,” says Lyulko. Asked if she planned to go home, the 42-year-old said there still were too many open questions. “I honestly don’t know,” Lyulko said, adding that most of those returning speak only Ukrainian or Russian, and are therefore struggling to find work and integrate.

An official survey of 7,000 Ukrainian refugees in Germany, published July 12, found that 44% intended to stay either for several years or for good, up 5 percentage points from last summer. Three quarters were taking German language classes or had completed one, an important precondition of work.

Germany hosts about 1 million refugees from Ukraine. The largest number are in Poland, where Alona Sirant arrived from Khmelnytskyi, in western Ukraine, speaking only a few rudimentary words of the language.

Though university educated, the 29-year-old, divorced single mother struggled at first, finding work at a small supermarket. But then she asked the principal at her son’s new school if there was work available. There was, and she became a teaching assistant.

In Ukraine she had an uninspiring job as an office manager. But in Poland, she says, she has found herself: She loves teaching and the kids, her son has friends, and both are happy. She’s in no rush to go home.

“Of course, I wish I could go to Ukraine and visit my parents, but I’m fine here,” she says. “I see no sense in going to Ukraine now. Those sirens howling, explosions... No.”

--With assistance from Andrew Langley and Aliaksandr Kudrytski.

(Updates to clarify that the analyst quoted in the 14th paragraph was speaking in a personal capacity.)