An inflation-induced tax boom has left UK government borrowing on track to come in significantly below official forecasts this year, figures Friday show.

The budget deficit in the first six months of the fiscal year was £81.7 billion ($99 billion) - £15.3 billion above the same period last year but £19.8 billion less than the Office for Budget Responsibility forecast in March.

The shortfall in September alone was £14.3 billion, the Office for National Statistics said, less than the £18.3 billion median estimate in a Bloomberg survey.

The undershoot at the halfway mark of 2023-24 provides a boost for Chancellor Jeremy Hunt as he prepares for his autumn economic statement on Nov. 22.

The windfall largely reflects the strength of income and value-added tax receipts as high inflation boosts wages and company profits. In its Green Budget this week, the Institute for Fiscal Studies said the deficit was likely to total £112 billion in 2023-24, or 4.2% of GDP, rather than the £131.6 billion OBR forecast.

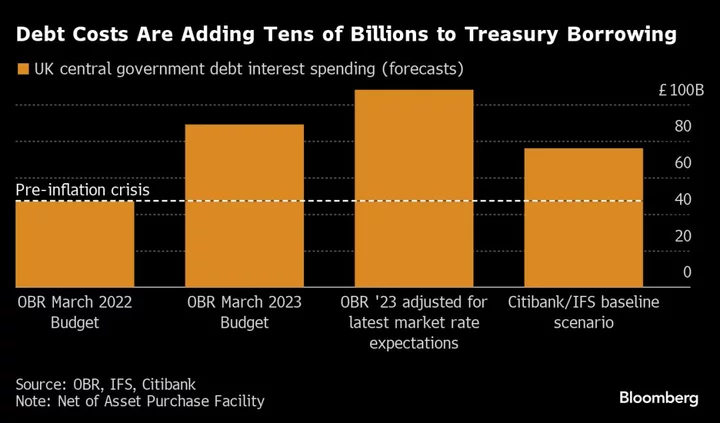

However, Conservatives hoping for big tax cuts to boost the ruling party before a general election expected next year are almost certain to be disappointed, with Hunt making clear he has no room for maneuver because elevated interest rates are driving up debt-servicing costs.

Public sector net debt was almost £2.6 trillion at the end of September, around 97.8% of GDP. That is the highest level since the early 1960s, the ONS said.

In response to today’s public finances data, Hunt said: “This is clearly not sustainable; we need to get debt falling and reduce public sector waste.”

Speaking to reporters in Marrakech a week ago, he said he would have to take “difficult decisions” after a deterioration in the financial picture since the spring.

Higher interest rates than the OBR forecast in March have added between £20 billion to £30 billion to the annual cost of servicing the national debt, he said, making it harder for Hunt to meet a self-imposed target to have debt falling as a share of GDP in five years.

In March, the Treasury was judged to have a margin of just £6.5 billion against the target, the smallest margin since the OBR was set up to monitor the public finances in 2010.

Should the OBR cut its relatively optimistic growth forecasts next month, as many economists expect, Hunt could even find himself having to extend a squeeze on government spending in order to fill a multi-billion-pound hole in the public finances.

Rising prices continued to provide a windfall for the government. Central government tax receipts in September were £57.4 billion, £3.7 billion more than last year as income taxes and VAT alone pulled in an extra £3.3 billion, the ONS said.

Total government revenues so far in 2023-24 are 5.6% higher than a year earlier and 3.3% above the OBR forecasts - a £15 billion overshoot compared with OBR projections. Over the six months, revenues from income tax, VAT and corporation tax were £28.7 billion higher than last year.

That’s offsetting pressures on government spending from debt costs, welfare payments and public-sector pay — all factors driven by inflation. Spending was 10.8% higher than last year for the six months but roughly in line with the OBR forecast.

The deficit for April to August revised down by £2.3 billion.

Helping the government’s position last month was an improvement in the cost of servicing the national debt as a result of a 0.6% decline in the retail prices index of inflation between August and September.

That resulted in a “negative capital uplift” of £3.2 billion on index linked gilts and lowered September’s debt interest cost to just £700 million, £4.1 billion below the OBR forecast and the third lowest monthly debt interest payment since 1997. For the first six months, debt interest fell 24% compared with last year to £44 billion.

The big increases in spending this year have been on benefits, which have risen 12.3% and public sector staff costs, which are up 12.9%. In cash terms those two factors alone have added £27 billion to spending in the year to September.