The government has no policy to adopt it, the public doesn’t want it and the central bank is keen to keep control of interest rates.

The commitment to eventually switch to the euro was a key condition of joining the European Union. But after almost two decades, the Czech Republic — like all the largest post-communist members — isn’t anywhere close.

Instead, executives are increasingly taking the matter into their own hands, gradually nudging the economy to a place where politicians and monetary policy makers seemingly don’t want to go.

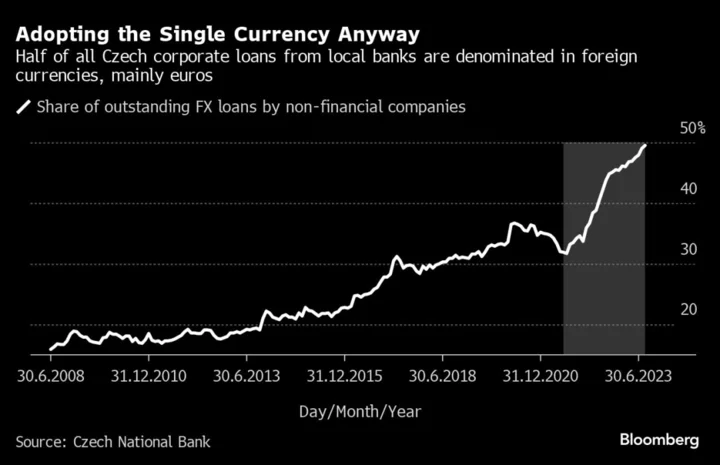

Figures from the Czech central bank show that for the first time half of all outstanding corporate loans from local banks in the country are denominated in foreign currencies — overwhelmingly euros — and the number is even higher if credit from foreign banks is included. On top of that, about 20% of all domestic trade between Czech companies happens in euros, while many exporters pay their local suppliers in euros instead of koruna.

“The koruna is only a part-time currency because the big businesses dominating the economy have mostly switched to the euro,” said Tomas Kolar, chief executive officer of Linet Group SE, a maker of high-tech hospital beds and other equipment. “There is no good reason not to have the euro, but politicians are afraid to even raise the issue, let alone explain it to voters.”

Almost all of the Czech company’s €360 million ($381 million) of sales come from exports to customers in 150 countries, said Kolar. He’s switched most of his operations from koruna to the euro to minimize the losses from market swings.

Since the EU started its big eastward expansion in 2004, Slovenia, Slovakia, the three Baltic States and most recently Croatia have transitioned to the euro. Bulgaria also aspires to make the move. The Czech Republic, along with Hungary and Poland, have repeatedly delayed ditching their own currencies.

Read More: Swedes Discuss Once-Taboo Idea of Using Euro

In Hungary, a year-long recession and a brush with a forint crisis prompted some business leaders to demand at least a timeline for euro adoption. Data show that 42% of loans in the country are in foreign currencies.

The Czechs, though, are in a better position to meet conditions for the currency switch, known as Maastricht criteria. The nation’s debt is one of the EU’s lowest relative to the size of the economy, and it’s on track to meet the inflation and budget deficit requirements.

Few countries, though, are as Euroskeptic as the Czech Republic. Polling among EU members that haven’t adopted the single currency showed the Czechs with the smallest share of people supporting the switch, according to the latest survey from Eurobarometer.

Concerns include the potential cost of bailing out another euro member and that goods and services will get more expensive, and given the lukewarm public attitude, the topic barely makes it onto the political agenda. Four of the five parties in the current ruling coalition support the switch, but the dominant Civic Democrats managed to prevent any specific goals from being included in the government program.

“It’s outside the government policy in this election term,” Finance Minister Zbynek Stanjura, who is also deputy chairman of the Civic Democrats, told a party convention earlier this year where regional officials debated the move.

While the decision is purely in the hands of the government, the Czech National Bank is also against giving up its currency and powers. Officials have argued that an independent monetary policy works as a buffer against global shocks, and that overshadows potential benefits like elimination of the conversion costs or currency risks for businesses.

Deputy Governor Jan Frait has criticized the obligation to join the EU’s banking union before actually entering the currency zone, which he said meant relinquishing the supervision of the domestic industry — one of the best capitalized in Europe — without any guarantee of the time for entering the euro zone itself.

“The conditions that are currently set for euro adoption are demeaning for the Czech Republic,” Frait said in an interview. “In my view, this isn’t worth doing for us now. If the political representation makes the decision to enter the euro zone, then I think we should negotiate more dignified terms.”

That leaves companies with a problem in a country that sells two-third of its exports to the 20-member euro region. As currencies become more volatile due to geopolitical instability such as Russia’s war in Ukraine or the Israel-Hamas conflict, integration with the €13 trillion economic bloc offers more protection, executives say.

Heightened koruna swings in recent years are boosting the appeal of the single currency. The central bank has had to intervene to support the koruna, while borrowing costs are higher than in the euro region.

The latest bout of volatility was caused by a surprisingly large interest-rate cut in neighboring Poland in September. That, as Linet’s Kolar put it, shows that without the euro foreign investors see the Czech Republic as a “risky emerging market.”

Switching to the euro for financing and paying local suppliers removes a large part of the currency risk — but not all of it, according to Zuzana Ceralova Petrofova, president of high-end piano maker Petrof, which her family founded 159 years ago.

“As an exporter receiving 90% of sales in euros or dollars, we have been wishing to have the euro for a long time,” Ceralova Petrofova wrote in a Confederation of Industry magazine earlier this year. “We have to pay workers, energy bills and some materials in koruna, which is expensive for us.” She wasn’t available for further comment.

In many aspects, the country of roughly 11 million people is a success story of the post-communist transformation. A booming car industry helped Czechs surpass some of the older EU members, like Spain and Greece, in living standards measured by gross domestic product per capita.

Businesses may win some concessions. There are legislative proposals that would allow them to do accounting in a foreign currency, with several lawmakers ultimately envisaging companies paying taxes in euros, dollars or pounds.

Volkswagen AG’s business Skoda Auto AS, the country’s biggest manufacturer, has been calling for the euro for years. It already shifted its accounting to euros this year because it uses the common currency for most of its transactions, including payments to many local suppliers.

With exporters forming the backbone of the economy, more and more enterprises will take part in “this trend of spontaneous euroization,” said Radek Spicar, vice president of the Confederation of Industry, the country’s main business lobby representing over 11,000 employers. “Under the influence of large companies, other parts of the economy will also gradually transition to doing business in euros.”

Get the Eastern Europe Edition newsletter, delivered every Tuesday, for insights from our reporters into what’s shaping economics and investments from the Baltic Sea to the Balkans.

--With assistance from Zoltan Simon.