Billions of dollars from humanitarian aid and rising trade with Asian neighbors has propelled Afghanistan’s currency to the top of global rankings this quarter — an unusual spot for a poverty-stricken country with one of the world’s worst human rights records.

The ruling Taliban, which seized power two years ago, has also unleashed a series of measures to keep the afghani in a stronghold, including banning the use of dollars and Pakistani rupees in local transactions and tightening restrictions on bringing greenbacks outside the country. It has made online trading illegal and threatened those who violate the rules with imprisonment.

The currency controls, cash inflows and other remittances have helped the afghani climb around 9% this quarter, outpacing the likes of the Colombian peso’s 3% gain, data compiled by Bloomberg show. The afghani is up about 14% for the year, putting it third on the global list, behind the currencies of Colombia and Sri Lanka.

Yet the paring of the currency’s losses seen after regime change also belies the dramatic upheaval that persists on the ground with Afghanistan largely cut off from the global financial system because of sanctions.

Unemployment is rampant, two thirds of households struggle to afford basic items and inflation has turned into deflation, according to a World Bank report. Planeloads of US dollars arrived almost weekly from the United Nations to support the poor, some of up to $40 million, for at least 18 months since the end of 2021.

“The hard currency controls are working, but the economic, social and political instability will render this rise in the currency as a short-term phenomenon,” said Kamran Bokhari, an expert in Middle Eastern, Central and South Asian affairs at the Washington—based New Lines Institute for Strategy & Policy.

Market Stalls

In Afghanistan, foreign exchange is now traded largely via money changers - locally called sarrafs - who put up stalls in markets or operate from shops in cities and villages. The bustling, open-air market Sarai Shahzada in Kabul is the de-facto financial hub of the country, where the equivalent of tens of millions of dollars cross hands every day. There is no limit to trading, according to the central bank.

Because of the financial sanctions, almost all remittances are now transferred to Afghanistan via a centuries-old Hawala money transfer system practiced in regions including the Middle East. Hawala is a key part of the sarrafs’ business.

The UN, which estimated that Afghanistan needs about $3.2 billion of aid this year, has deployed about $1.1 billion of that, according to the world body’s financial tracking service. Last year, the organization spent around $4 billion as half of Afghanistan’s 41 million people faced life-threatening hunger.

The World Bank forecasts that the economy will stop contracting this year, posting growth of 2% to 3% until 2025, though it warned of risks such as a reduction in global aid as the Taliban intensifies its repression of women.

“Tightened restriction on foreign exchange transactions and a very gradual improvement in trade is pushing up demand for the afghani,” said Anwita Basu, head of Europe country risk at BMI in London. The afghani is likely to stabilize at current levels until the end of the year, she said.

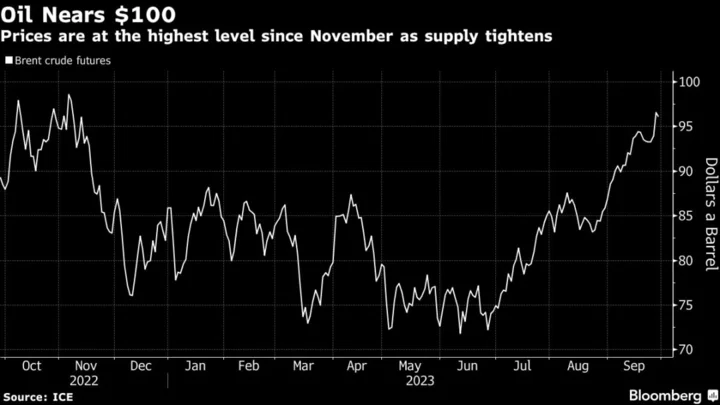

A stronger currency can help curb inflation pressure for critical imports for Afghanistan such as oil, particularly as crude prices approach $100 a barrel.

Mineral Resources

The cash-strapped Taliban administration is seeking investment into the country’s rich resources, including lithium, which are totally estimated to be worth as much as $3 trillion. Chinese, British, and Turkish companies were involved in $6.5 billion of contracts given out this month to build large-scale iron, ore and gold mines. The Taliban also inked a deal in January with a Chinese company for oil extraction.

In May, China and Pakistan also agreed to extend the Belt and Road Initiative to Afghanistan, potentially drawing in billions of dollars to fund infrastructure projects. In a sign of thawing ties, a US business delegation in September co-hosted a conference in Kabul to lure global investors.

Meanwhile, dollars being smuggled into Afghanistan from Pakistan have also given a lifeline to the Taliban in previous months. Da Afghanistan Bank, the country’s central bank, is auctioning up to $16 million almost every week to support the currency, said spokesman Hassibullah Noori.

As pressure on the currency eased, the central bank has increased the limit for dollar withdrawals to $40,000 per month for businesses from $25,000 and $600 a week for individuals from $200 two years ago. The afghani traded around 78.50 per dollar on Monday.

Dire Situation

Still, even as cash flows in, the humanitarian situation and financial outlook remains dire.

The US had agreed to release $3.5 billion out of $9.5 billion of frozen foreign-exchange reserves, but put the plan on hold after it found that the central bank lacks independence from the Taliban and has deficiencies in anti-money laundering controls and in countering terrorism financing, according to a July report by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction.

The UN has warned that if foreign aid slides 30% this year, that would lower per capita income to $306, a 40% drop from 2020 levels.

The sweeping restrictions against women have also inflamed divisions within the Taliban administration, with some openly criticizing their supreme leader Haibatullah Akhundzada. Akhundzada has issued orders prohibiting women from education, working, visiting public parks, using gyms, and traveling long distances without a male escort.

A UN report this month said the Taliban committed more than 1600 cases of human rights violations including torture from January 2022 through the end of July this year during the arrest and detention of people.

Meanwhile, a 2023 Pentagon assessment found that the Islamic State is again using Afghanistan as a base to plan attacks across the world, the Washington Post has reported. The terrorist group has also stepped up attacks in Afghanistan, such as the killing of a deputy governor and the bombing of a mosque

Islamic State militants have threatened to target Chinese, Indian, and Iranian embassies in Afghanistan, according to the UN.

“Ultimately, political stability will make or break the currency – if the Taliban lose control at home, then the currency too will suffer,” BMI’s Basu said.

--With assistance from Faseeh Mangi.

Author: Karl Lester M. Yap and Eltaf Najafizada