Rishi Sunak has a decent chance of delivering his promise to halve UK inflation this year, according to the Bank of England. But that is about as good as the latest central bank forecasts get for the prime minister, who was hoping to fight a 2024 general election with a much-improved economy.

Instead, the bank’s models show Sunak risks going to the polls with households still feeling the effects of 14 consecutive interest-rate increases to tame the highest inflation in decades. The BOE delivered the latest hike Thursday with a warning that borrowing costs — which have fueled an historic cost-of-living crunch — could stay elevated through at least next year and perhaps longer.

A general election must be held no later than January 2025, and Sunak is said to prefer November next year to allow the economy time to recover as he tries to overturn the opposition Labour Party’s formidable lead in opinion polls.

In power for 13 years already, the Conservatives are likely to fail on the core question of whether voters feel better off than in 2010. That leaves Sunak trying to show he can be trusted to turn things around. A healthier economy is likely to be key, but the following charts show what he may be up against.

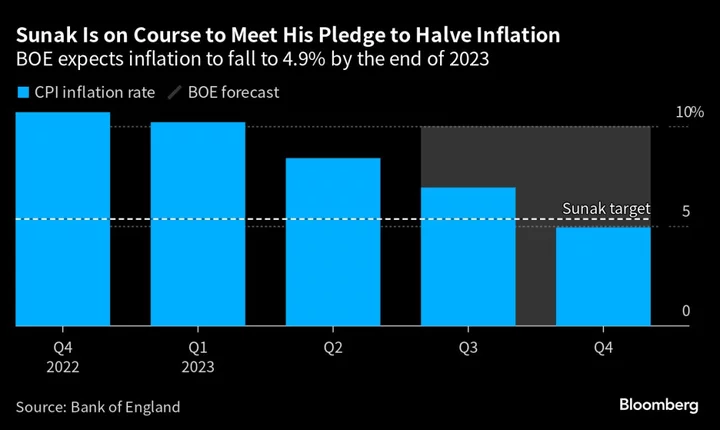

Inflation Relief

First the good news for Sunak, who made halving the rate of inflation by the end of 2023 one of five key tests he wants voters to judge him on. The BOE expects inflation to fall to 4.9% in the fourth quarter from 10.7% a year earlier, so he meets his target with a little room to spare. “People can see light at the end of the tunnel” on inflation, Sunak said this week before the BOE rate hike.

Setting an economic target and then meeting it is central to the image Sunak has tried to put to voters since taking over from the chaotic administration of Liz Truss last year. Yet the political upside could be limited because having endured double-digit inflation for so long, slowing the pace of price rises is not going to leave Britons feeling that the squeeze on living standards is over.

Recession Risk

Given the scale of the inflation shock, consumers have proved surprisingly resilient. The BOE now expects the economy to fully recover its pre-pandemic size in the current quarter — earlier than estimated three months ago.

After that, though, the bank sees the UK avoiding a recession by only the narrowest of margins, and officials concede the risks of one are significant. The economy, which Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt told Sky News is in a “low-growth trap,” is expected to expand in only one quarter next year.

That is far from ideal for Sunak. If he goes ahead with a November vote, knocking on doors as winter nears — with a moribund economy souring the public mood — is not a prospect Tory activists are likely to relish. Hunt said he will use a fiscal statement this autumn to kickstart growth.

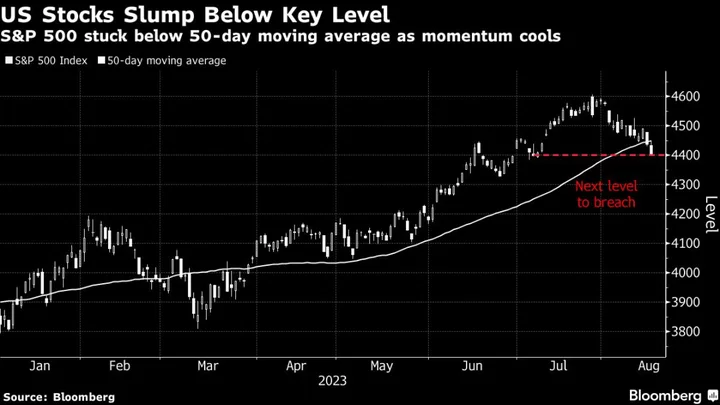

More Rate Pain

The message from the BOE is that interest rates may stay higher for longer than expected. While borrowing costs may be close to peaking — markets are pricing in two more quarter-point increases — the inflation battle is not over.

Read More: Bailey Says ‘Last Mile’ of UK’s Inflation Fight Will Take Time

“It’s the last mile which obviously is where policy is really doing the work, and we’re going to have to see policy stay restrictive,” Governor Andrew Bailey told Bloomberg TV. “It’s going to have to remain restrictive to have this effect of bringing inflation down, and particularly next year.”

That means little relief for homeowners with a mortgage, with millions facing a severe shock as they are forced to refinance cheap fixed-rate deals at significantly higher rates. Money markets see the BOE raising rates to a 16-year high of 5.75% by November, with little prospect of a cut until a year later.

Job Prospects

A strong labor market, falling energy prices and an extension of government support for gas and electricity bills has supported after-tax incomes, which the BOE expects to grow by around 1.25% this year after adjusting for inflation.

But the next two years are a different story, with officials sharply downgrading their forecasts to show living standards effectively flatlining over the period.

The red-hot labor market is also showing signs of cooling, and the bank now expects the unemployment rate to climb to 4.5% by the end of 2024. In that scenario, an extra 200,000 people will be looking for work by the time of the election. Sunak won’t even be able to point to upcoming improvement — joblessness is expected to climb further in 2025 and approach 5% in 2026.