About 150 miles northwest of Tokyo, in a slivered valley that leads to the Sea of Japan, lies a sleepy pocket of the nation’s ski country called Myoko Kogen. Bustling in the 1980s bubble era with young skiers and neon-lit streets, the area has now seen better days.

But in the coming years Ken Chan, the former Japan head of Singapore sovereign wealth fund GIC Pte, aims to invest $1.4 billion transforming it into a luxury skiing paradise to rival Aspen, Whistler and St. Moritz. For two years his investment firm has bought surrounding land at cut-rate prices thanks to the plunging yen. And by 2026 he aims to have international hotels in place, alongside housing for thousands of workers.

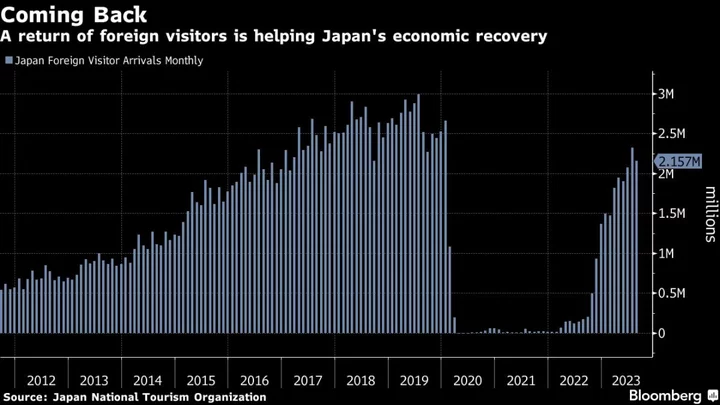

The plan to put Myoko on the world tourism map is a cornerstone project for Chan and his company Patience Capital Group, which manages $500 million and also invests in residential real estate assets in Japan. It comes as more global investors look to get in on the country’s red-hot tourism rebound, and its ski slopes become more celebrated.

“I always say that we can’t put this project into a bag and take it back to Singapore — this is permanent,” Chan, 56, said in an interview at his Tokyo office. “We’re ready to do this in a very proper way and launch it big time.”

Chan has just taken the first step on what he hopes to pin his legacy on. Patience has raised 35 billion yen ($235 million) from institutional investors in Japan and Singapore for its Japan Tourism Fund One, with much of that tagged for the ski initiative.

By December, he expects to announce at least two to three winners of a hotel tender process that has attracted more than 10 bids from global giants.

Eventually, over at least three phases, Chan anticipates it will take about 10 years and around 210 billion yen for his vision to reach fruition — with the mountains in the Myoko area filled with flagship boutiques and world-class dining. Chan envisages travelers taking a four-hour chauffeured drive or a roughly two-hour bullet train from Tokyo before entering the luxury bubble, where they’ll either ski in and out of resorts in winter, and spend the warmer months hiking or sending their children to summer camps.

There are risks for a project in its infancy. Funding is one — just the first phase will need almost half a billion dollars in investments over the next three to four years alone, according to Chan’s estimates.

The number of skiers and snowboarders in Japan has also been declining — down about 75% in 2020 from its peak in the late 1990s, according to the Japan Productivity Center. That means Chan will need to rely on foreign tourists. It remains unclear how locals will take the influx of rich travelers and the workforce needed to service them.

Read more: Everyone Wants to Ski Japan But the Japanese: Gearoid Reidy

Chan is confident that he can work with residents and people will come to Myoko, already known among buffs for its powdery snow and one of the nation’s longest ski runs. His ties to Japan run deep — he was born in the island nation, the son of a Singaporean doctor who lived in the country until Chan was 6. After graduating from the University of Southern California, Chan returned to Japan and then Singapore to work in information technology and finance roles.

Chan joined GIC at the turn of the century, when the wealth fund was repeatedly losing bids for Japanese real estate and wanted a Singaporean with the cultural skills and experience to work in Tokyo. In 2004, he was transferred to Japan as its representative in the country, where he built relationships with top executives such as Shinichi Sasaki, the former deputy president of trading giant Sumitomo Corp.

“Ken’s been smart about bringing on investors to this project,” said Sasaki, who met Chan in 2011 and is now an adviser at Patience. “He’s got a mix of overseas institutional and retail investors, as well as large and local Japanese banks. It’s a good balance.”

After almost 20 years, Chan left GIC in 2019 to strike out on his own. His firm also oversees the Japan Residential Opportunities Fund, with 40 billion yen in assets under management. It’s now in the market to raise 25 billion yen for a second residential fund, targeting annualized returns of 15%.

But it’s clear that he has a special passion for the ski project, as he runs through charts and maps, pointing out properties in negotiations and where he plans to install housing for workers. His firm already owns 350 hectares of land and parts of two mountains straddling Niigata and Nagano prefectures, including Madarao Mountain Resort, he said.

Yosuke Kanehira, who runs the Good Mountains restaurant a 30 minute drive away in the nearby town of Iiyama, reckons overseas tourists would reinvigorate resorts like Madarao.

“Madarao has mainly been full of cheap tours with low profit margins,” Kanehira said. “If a foreign fund buys the area and brings in foreign visitors, I’d look forward to that,” he said, while acknowledging that some older locals may dislike it.

In Nagano, the government welcomes new ski resorts as long as they gain the understanding of residents, said Norihiko Wakabayashi, head of the prefecture’s Tourism Promotion Group.

“It’s clear that the number of visitors to ski resorts is decreasing year by year,” Wakabayashi said. “On the other hand, inbound visitors are expected to increase even more. So I’m glad to see revitalization of the ski industry.”

Like many rural areas in Japan, the city of Myoko has seen its population drastically shrink over the past 30 years.

While Niseko — Japan’s best-known ski hub — took about 19 years to reach its current state without a singular driver, Chan is planning the development from scratch, and believes owning the land will streamline the process.

“The company I’ve set up is going to go beyond me,” he said. “This is going to benefit the next generation.”

--With assistance from Justin Ocean.

Author: David Ramli, Lisa Du and Yuji Okada