Tycoon Rene Benko’s Signa filed for insolvency after a last-ditch attempt to raise emergency funding failed, making the co-owner of New York’s Chrysler building one of the most prominent casualties of Europe’s property crisis.

The management of Signa Holding GmbH said it made the filing on Wednesday in Vienna with the goal of managing its restructuring as a debtor-in-possession, according to an emailed statement from the company.

“Despite considerable efforts in recent weeks, the necessary liquidity for an out-of-court restructuring could not be sufficiently secured,” Benko’s main holding company said in the statement. “The aim is to continue business operations within the framework of self-administration and the sustainable restructuring of the company.”

The filing is a bitter blow for Benko. The self-made mogul built a portfolio that included Selfridges department store in London, luxury malls in Vienna and an historic hotel in Venice. The 46-year-old Austrian was known to boast that only the British royal family and the Catholic church could rival his array of exclusive properties, which were valued at €23 billion ($25 billion) at the end of last year.

What sets Benko apart from many other property investors is that he continued to make high-profile acquisitions even as challenges to his debt-laden structure started to surface in recent years. The end of the cheap-money era then triggered a drop in valuations and a cash crunch, and Signa’s obscure corporate structure left it especially vulnerable.

In frantic talks to secure financing to plug up to €600 million of short-term liquidity needs, Signa reached out to a wide range of financiers including Mubadala Investment Co., Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, Attestor Capital and Elliott Investment Management, people familiar with the discussions have said. Signa’s complexity and the tight time frame for a deal were too much to overcome.

The fallout from the insolvency is likely to be another blow for Europe’s battered commercial real estate sector by potentially forcing a fire sale of assets and resetting valuations even lower.

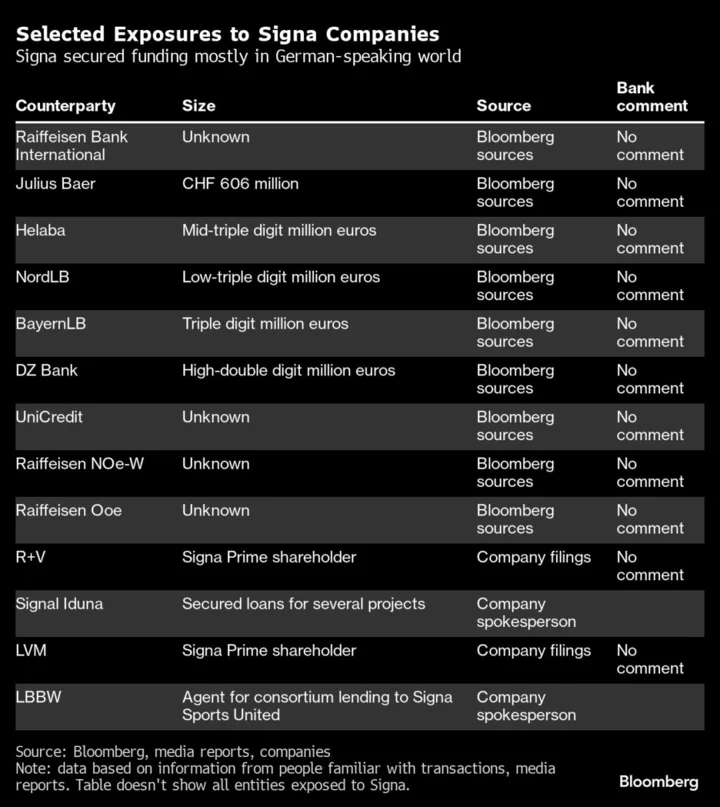

Financial contagion though could be limited. Signa’s largest exposure is toward banks for credit to fund acquisitions and construction work on development projects, such as Hamburg’s Elbtower. Those loans are often secured against the property, meaning banks may be well-positioned to recoup losses.

Shareholders, on the other hand, are in store for deep losses. Despite contributing almost €1 billion in fresh capital to the two largest Signa units just last year, Benko’s once-loyal backers balked at extending more money. A group including Haselsteiner pushed Signa’s founder to step aside and recruited restructuring experts Arndt Geiwitz and Ralf Schmitz to spearhead a turnaround. But it was too late.

In his rise to one of Europe’s biggest property dealmakers, Benko had gained the trust of Europe’s elite, counting Austrian construction tycoon Hans Peter Haselsteiner, German transportation magnate Klaus-Michael Kuehne and France’s Peugeot family among his investors. They now stand to lose heavily as administrators pick through Signa’s complex structure to repay creditors.

The implosion will leave a wake of uncertainty, especially in Germany. Construction work had been halted at the Elbtower and other sites, and dozens of German cities face closures of Signa’s Galeria department stores, leaving a yawning gap in downtown shopping districts.

One winner could be Thailand’s Central Group. The retail conglomerate has already secured control of Selfridges’ operating company by converting a loan into equity earlier this month. The company owned by the Chirathivat family is also a co-owner with Benko in Switzerland’s Globus chain and Berlin’s KaDeWe.

(Updates throughout.)