The slump in Russia’s ruble shows little sign of abating amid high currency outflows and worsening foreign trade conditions as sanctions over the war in Ukraine take their toll on the economy.

The ruble has weakened by 24% against the dollar so far this year, placing it among the three worst emerging-market performers with the Turkish lira and the Argentine peso. The currency weakened past 98 per dollar on Wednesday and is nearing 100 to the greenback, a level last seen during the first month after President Vladimir Putin ordered the February 2022 invasion.

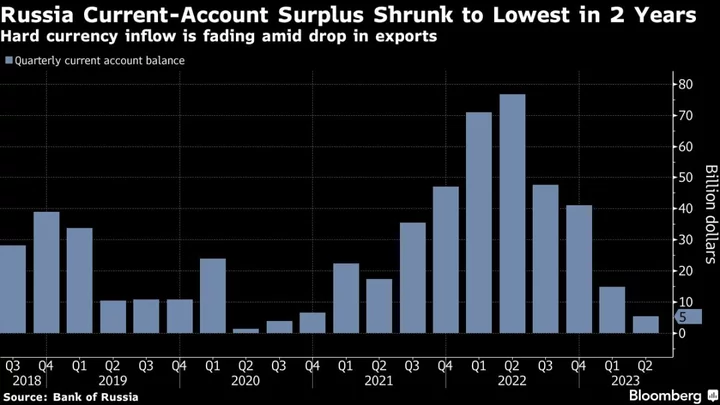

The current account surplus — roughly the difference between exports and imports - declined to $25.2 billion in the first seven months of this year, down from $165.4 billion in the same period in 2022, data published Wednesday by the Bank of Russia showed. The surplus was $1.8 billion in July compared with $17.8 billion a year earlier, according to the bank.

Central bank Governor Elvira Nabiullina has repeatedly pointed to the deterioration in foreign trade conditions as the main reason for the ruble’s collapse, while ruling out intervention to support the exchange rate. The currency has almost halved in value from last year’s capital-control peak amid increased government spending, falling energy revenues and a move by Russians to put funds in foreign accounts.

The most recent central bank data showed that major Russian exporters sold 84% of their foreign exchange revenues on the market in June. But their proceeds — a key source of hard currency for Russia since the invasion — declined to just $6.9 billion in July from $16.8 billion in the same period last year.

While flows of imports remain stable, restrictions on Russia’s energy sales, including an oil price ceiling aimed at limiting the Kremlin’s ability to feed its war machine, have led to a steady decline in exports. Coupled with an increase of the ruble’s share in trade, the inflow of hard currency is falling.

The negative trend hasn’t reversed even as Russia’s flagship Urals crude last month breached the price cap set by the Group of Seven nations.

If that move holds, then the inflow of foreign currency to the Russian market should gradually increase, according to Andrey Kochetkov, an analyst at Otkritie Bank FC in Moscow. Still, the ruble’s decline isn’t solely due to the deterioration of the trade balance, as “there is capital flight, including the withdrawal of money by exiting foreign companies,” he said.

What Bloomberg Economics says

Ruble weakness comes down to capital outflow, which itself resulted from mis-calibrated domestic policy. The government’s 14% year-on-year spending surge boosts demand for imports at a time when export revenue is dwindling. At the same time, households have moved around $40 billion to foreign banks as ruble interest rates have fallen short of inflation expectations and a growing number of Russian banks have been cut off from global payment systems.

Alexander Isakov, Russia economist

Central bank data published Monday showed deposits of Russian citizens in foreign banks increased in June by more than half a trillion rubles, the most since December. The volume of Russian money held abroad reached 6.4 trillion rubles ($66 billion) as of June 30.

The ruble may find more support in the coming months if the central bank hikes borrowing costs to 9.5% and the authorities slow expenditure, according to Bloomberg Economics Russia economist Alexander Isakov.

The bank hiked its key interest rate by a percentage point to 8.5% last month, the first increase since emergency measures imposed immediately after the invasion, as policymakers responded to inflationary risks from government spending, sanctions and labor shortages caused by the call-up of men to fight in Ukraine.

The ruble is now without the last source of support that it had from regular Finance Ministry sales of foreign exchange as the financial authorities switched to purchases under the fiscal rule from August.

The psychologically important mark of 100 per dollar may be reached soon, according to George Vaschenko, deputy head of research at Freedom Finance Global in Astana. “I wouldn’t expect the weakening trend to stop,” he said.

(Updates with current account data in third paragraph)