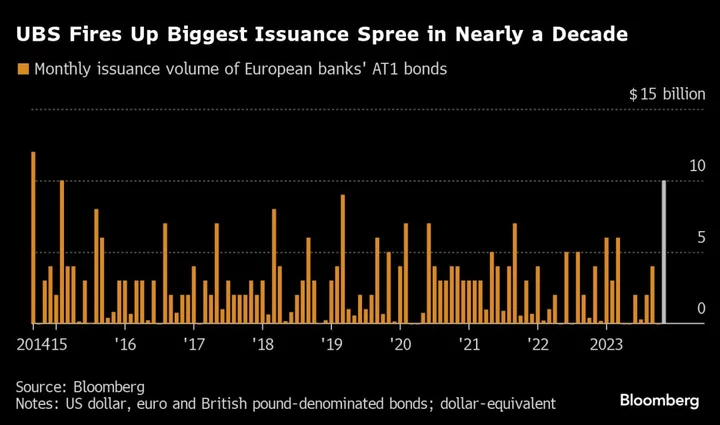

A day that started with a blunt call to investors ended with incredulous fund managers at Algebris Investments facing double-digit losses. It was March 20, and the Swiss government had just taken the unprecedented decision to wipe out $17.3 billion of junior debt as part of a forced merger between Credit Suisse Group AG and UBS Group AG.The move set off a global slump in the price of additional tier 1 bonds, as the riskiest banking debt is known, with some forecasting that it would serve as a death knell for the entire asset class. As one of the world’s top buyers of AT1s, Algebris needed to talk to its investors. On the call, CEO Davide Serra laid the blame on Switzerland, saying that the country would become a pariah in the bond market for what it had done.Fast forward eight months and the picture couldn’t look more different. Algebris’s biggest fund is on track for its best annual return since 2020, while many of the investors who warned the AT1 sector wouldn’t survive are now rushing to get their hands on the bonds. Once again, Switzerland is at the center of the dramatic turn in events after UBS sold a batch of AT1 bonds earlier this month that received tens of billions of dollars in orders. The issuance blitz that followed was the biggest in almost a decade, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. “Everyone was wrong on the death of the AT1 market,” Algebris Chief Investment Officer Sebastiano Pirro said in an interview. “In the end, Credit Suisse’s failure will likely make more money for our investors over five years than we would have otherwise, as we never thought we could get new issues from strong names at yields of more than 9%.”

Also called contingent convertibles or CoCos, AT1s were dreamed up after the global financial crisis to shift the burden of bank rescues onto bondholders and away from taxpayers, replacing previous iterations that tried and failed to serve that purpose. They count toward the capital that regulators require banks to hold against potential loan losses, meaning they play a vital role in ensuring financial sector stability in Europe.The Credit Suisse collapse was the first major test of that regulatory framework and in many respects it was a spectacular success. By absorbing losses and preventing the need for a taxpayer bailout, AT1s did exactly what they were designed to do. But Switzerland’s decision to effectively rank them below equities in the pecking order also posed a major potential problem: If fixed income investors were now too spooked to touch AT1s again, the European banking system would lose a crucial tool in its efforts to shore itself up against shocks.

Call Them AT1s or CoCos, Here’s Why They Can Blow Up: QuickTakeSoaring demand for the securities over the past month suggests that this particular crisis has blown over. While UBS’s orderbook of more than $36 billion hasn’t been repeated in deals by the likes of Barclays Plc and Banco Santander SA, orders exceeding the amount issued by several times have been routine in recent weeks. European banks’ AT1s have returned 2.6% in dollar terms this year, rebounding from losses of more than 15% in March.Andy Townsend, the group treasurer of Close Brothers Group Plc, a London-based merchant bank that sold its debut AT1 bond earlier this month, had been so uncertain about the market’s recovery that he quipped back in March that the bank’s long-planned issuance would be a matter for his successor to decide. “There was more momentum than any of us had expected,” Townsend said in an interview, noting the “broad participation from the investment community” in Close Brothers’ bond sale.

A major reason why the market was able to bounce back so quickly is that many see another European bank implosion as unlikely. The continent’s banks are mostly in good financial health, according to the European Banking Authority’s most recent assessment in July. The European Central Bank and the Bank of England were also quick to declare that, unlike in the Credit Suisse case, they would treat AT1 holders above shareholders in the event of another bank failure.“The risks haven’t gone away but they are priced in,” said Matthias Reschke, head of European investment grade finance at JPMorgan Chase & Co. “We had one issue with one bank and I think that’s now over. Banks are relatively well capitalized.”Demand has also been given a boost by a broader revival in global bond markets. The Bloomberg US Treasury Index shifted earlier this month to a positive return for the year as signs of slowing inflation and measured jobs growth unleashed a rally that sent benchmark yields tumbling from their highest in more than a decade. “Banks are opportunistic” and will seize on the revival in demand, said CreditSights analyst Puja Karia. Assuming conditions remain as favorable, she expects they will have little trouble replacing a record $30 billion of notes that are due to be called next year, and could easily raise $35 billion.Read More: Bond Market’s Dramatic Recovery Seen as Prelude to Broader Gains

Jerome Legras, head of research at Axiom Alternative Investments in Paris, had few qualms about partaking in UBS’s sale after being caught in the Credit Suisse writedown. Such episodes, he says, are the cost of doing business in this risky market. “It’s what we call the ‘fait du prince’ in French,” Legras said.

Phil Mesman, head of fixed income at $10 billion hedge fund Picton Mahoney in Toronto, says the UBS deal helped convince him that the market had shifted direction. Afterward, he boosted his already overweight positioning in junior bank debt, and says the recovery is just beginning.Legal Battles

Still, it hasn’t been an uninterrupted path to recovery and the market faces many hurdles. Even UBS’s own issue was months in the making, as the bank had to cope with volatility in government bond yields and concerns over the permanent writedown feature that doomed Credit Suisse bondholders. The bank responded by adding an equity conversion clause that will have to be voted on by shareholders.Many Credit Suisse investors still feel blindsided by what happened and Swiss regulators face years’ of legal battles with creditors who are trying to claw back their money. Filippo Alloatti, head of financials at Federated Hermes, says his firm is “less involved” in AT1s than it was before the Credit Suisse blowup because the episode exposed flaws in the market that are yet to be fixed.Algebris was one of a handful of investors that held firm following the Credit Suisse blowup, convinced that the market would rebound. In a March interview, Pirro called AT1s “a spectactular buy” because, he said, much of the selloff was related to margin calls and “panicky” investors. Pirro is now taking advantage of the issuance boom to add more of the securities to the €9.7 billion ($10.7 billion) fund that he runs for Algebris.“The environment now is very positive,” said Pirro. “Returns are probably lower than what I would have expected a year ago, but we've been through probably the worst event in the history of the space.”

Author: Tasos Vossos, Abhinav Ramnarayan and Cecile Gutscher