Argentina’s next president will take over in the middle of a financial emergency — which is par for the course in one of the world’s most dysfunctional economies.

Voters are heading to the polls on Sunday with the country expected to fall into recession for the sixth time in a decade, and inflation running above 140%. They are faced with two radically opposing proposals: the continuity of Economy Minister Sergio Massa, who vows to rein in fiscal spending without ending long-standing social rights, or the radical pledges of Javier Milei, who says he’d adopt the US dollar as Argentina’s currency as an alternative to the peso.

Neither is likely to result in a quick fix to Argentina’s economic woes because these problems have their roots in decades of mismanagement. Over its recent history, Argentine governments zig-zagged between policies, unable to pursue a consistent approach, and most investors fled. The result is that the country — once one of the region’s wealthiest — has an economy that looks increasingly unique, and not in a good way.

“Argentina is an outlier, and it has been for a long time,” said Martin Castellano, head of Latin America research at the Institute of International Finance. While other Latin American countries have carefully built sound economic institutions, Argentina has tilted toward volatility and stagnation.

With central bank reserves in the red, and the peso overvalued at official exchange rates, whoever wins the election will likely preside over a currency devaluation while trying to overhaul the public finances. “It’s an unavoidable adjustment that will result in another recession next year,” says Castellano.

Here are six charts illustrating the deep and distinctive trouble that Latin America’s third-largest economy is in:

From Richest to Poorest

Once one of the richest countries in Latin America, activity has stalled after facing multiple economic crisis in the past decades. Income per capita grew slower than most of its peers, rising on average around 1% per year since 1960. In the same period, neighboring Chile and Brazil multiplied their income by at least twice, according to World Bank data.

High inflation is only making matters worse, with 40% of Argentines living in poverty and 9% in extreme poverty, according to official data. That’s likely also to jeopardize the country’s ability to prosper in future generations since more than half of children up to 14 years old now live under poverty.

Losing Inflation Battle

Several Latin American countries suffered bouts of high inflation or even hyperinflation during the 1980s and early 1990s. Most of them managed to get a grip on price pressures — by adopting inflation-targeting regimes, allowing their currencies to float, and developing local-currency debt markets.

Not in Argentina. After a currency peg ended in 2002, the country’s central bank has been increasingly financing the government’s deficit via money printing. As a result, the annual inflation rate reached 143% in October and it’s expected to surpass 180% by the end of the year.

Recession Champion

Argentina has a long history of drastic economic swings, a result of weak and inconsistent policies that stand out even in a volatile neighborhood. A 2018 study by the World Bank found that between 1950 and 2016, the nation spent roughly one-third of the time in recession, the most of any country in the world except the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The economy is expected to contract again this year, according to the International Monetary Fund as well as analysts surveyed by Bloomberg. If those forecasts are correct, it will mean the economy has shrunk in almost half of the years since 1980.

Credit Desert

In most countries, the flow of bank credit to households and businesses is crucial for fueling economic growth. But in Argentina, years of high interest rates and inflation have been a barrier for both lenders and borrowers.

What’s more, private banks lend mainly to the ever-more-voracious government, leaving very little for individuals and companies. The result is that Argentina has one of the world’s lowest levels of credit to households, according to data from the Bank for International Settlements. Similarly, lending to businesses is only a fraction of the levels seen in neighbors Brazil and Chile.

BE Primer: Argentina’s Troubled Economy Faces Pivotal Vote

Sinking Peso

The Argentine peso has lost almost 100% of its face value in the past two decades, and once again this year it has posted one of the worst spot returns among the main emerging economies. “They missed the opportunity to move to a flexible foreign exchange regime and it has never been done properly,” says Castellano.

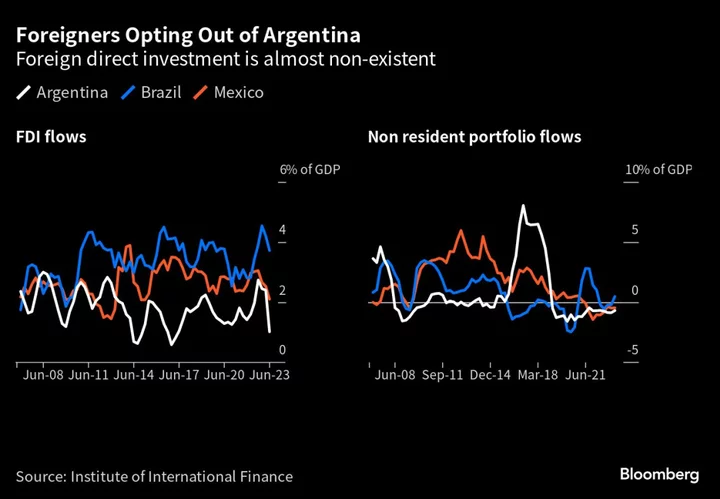

No Foreign Capital

Amid all the volatility, it’s no wonder that Argentina has lagged its peers in attracting global money. Foreign direct investment in recent years has been much lower than in Brazil or Mexico, the only two Latin American economies that are larger.

Argentina has a big domestic market, but companies seeking to tap it face risks including nationalization or inability to send their profits to headquarters. Importers and exporters also have a tough time selling their products due to a byzantine system of capital controls. As for short-term funds, the country saw a surge of inflows under the market-friendly government of Mauricio Macri between 2015 and 2019 — but most of the hot money fled again as Macri presided over another economic collapse.

(Updates inflation figures from second paragraph, adds chart on GDP per capita in first subhead.)