For years, Dutch payments fintech Adyen NV’s founders and management ran things their own way, thanks to some blowout growth.

During its listing in 2018 they didn’t feel the need to pre-brief investors — the shares doubled in the first two hours of trading all the same, making one of the founders an instant billionaire. There was no sounding of the traditional opening gong by management at the start of trading. After going public, the corporate suite kept a low profile, reporting results every six months and never awarding dividends.

Five years on, with growth slowing and the stock trounced, losing 57% in just the last three months, what were once seen as quaint and idiosyncratic ways are now being questioned, and investors are demanding a clear blueprint for how Adyen can get its mojo back. The company, which counts the likes of Cathie Wood’s Ark Investment Management and Singapore’s state investor Temasek Holdings Pte among shareholders — will need to reassure investors that it has a plan for growth in a cooling market with intensifying competition when its top brass briefs them in San Francisco on Wednesday.

“Investors will need to leave the investor day feeling more confident, which could mean the stock just stays where it is, which, in our view, is fairly appropriately valued,” said Craig Maurer, managing director at Financial Technology Partners, an investment banking firm focused on fintechs. “I think there’s more downside risk than upside risk actually, because as they showed on their earnings call, they didn’t exactly speak to investors on the level or with the humility that investors were hoping for, which is something that will need to change for confidence to be rebuilt.”

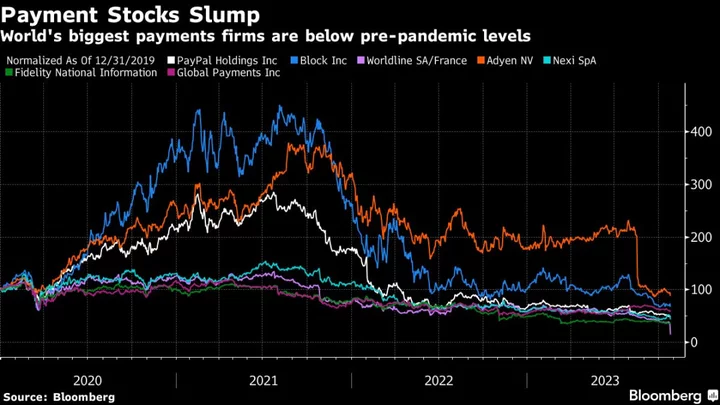

With the rout in the seven biggest payments stocks in the world erasing about $65 billion this year, the fintech sector is under pressure. The cooling of the online boom that once boosted such companies during the pandemic and the tightening of consumer purse strings because of higher inflation and interest rates suggest the end of the tunnel is not yet in sight for the industry. For Adyen, which still trades at about three times the earnings multiple of longer-established rival PayPal Holdings Inc., the pressure is particularly intense.

The first signs of trouble came when Adyen posted its half-yearly results in August, reporting an increase of about 22% in net revenue. While not a shabby rise for most industries, it was a far cry from the company’s 67% jump in the first half-year after it went public and was the slowest growth since then. Its shares sank by 39% on the day and continued to slide in the following days as investors wondered if pricing the company as a growth stock was justified.

“The problem right now with investors is they’re wondering if the competitive moat of Adyen is what they thought it was or are they operating in a more commoditized market,” says Bernstein Research analyst Harshita Rawat.

Adyen is basically a payments-processor, sitting between a merchant and the networks of the likes of Visa and Mastercard, executing complex cross-border and multi-currency settlements. It broke into the space once dominated by large banks and credit card issuers in 2006.

The company’s founders, including Co-Chief Executive Officer Pieter van der Does and Arnout Schuijff, believed the technology at the time was built on archaic infrastructure. The two Dutch executives, now in their 50s, had worked at Bibit, with Schuijff as its systems architect and Van der Does as its chief commercial officer. After Bibit was sold to Royal Bank of Scotland in 2004, the partners decided to give the payments business another go, founding Adyen, which means “start over again” in Suriname, a former Dutch colony in South America.

While traditional platforms provided separate gateway, risk management, processing and acquiring solutions, Adyen offered a single platform built in-house. It could support a merchant’s growth across the world, with better transparency and data insights.

“It was this novel streamlining of what was previously a very laborious and bank-based kind of connectivity to the payments landscape,” Lily Varon, principal analyst at Forrester Research said.

Adyen was soon processing online payments for large enterprises and through point-of sale terminals in physical stores. It got a boost in its platform business when eBay Inc. replaced its long-time partner PayPal with Adyen in 2018. With customers like Netflix Inc. and Spotify Technology SA, the fintech was put on the global map. As its merchant base grew, it often beat the top-end of medium-term goals it had set for itself. Market watchers and investors were smitten.

“In hindsight, Adyen had very much spoiled the market with going above and beyond with estimates and growth,” Jefferies International analyst Hannes Leitner said. “In the end, it was the managing of expectations, which was really the big miss.”

Adyen competes with such legacy players as Worldpay Inc. and new entrants including Stripe Inc and PayPal-owned Braintree. Stripe, was initially focused on helping small and medium businesses process payments over the internet before targeting larger firms, while Braintree has been largely US-centric. Adyen, on the other hand, grew from the complex European payments market with a focus on enterprise-level customers and, unlike rivals, avoided acquisitions.

By the time Covid-19 hit, such companies were lockdown heros, gaining business as people shopped from home. Stripe was valued at $95 billion when it raised funds in 2021. Adyen’s stock price vaulted to a high of €2,766 ($2,970) in 2021, from its IPO price of €240.

But as the world emerged from the pandemic, online spending slowed and uncertainty in the macro economic environment grew. Stripe’s valuation slumped to $50 billion; it planned to cut more than 1,000 jobs to bring its headcount back to almost 7,000, saying it had underestimated the impact of the slowdown. PayPal too said it would cut 2,000 jobs.

Adyen, meanwhile, continued to hire, and remained in an “investment mode,” Van der Does said late last year. Payroll rose by over 1,150 to about 3,330 employees last year, and the company said it would hire as many people this year, and ease recruitments in 2024.

Stripe, Adyen and Braintree together account for about $1.8 trillion, or a quarter of global e-commerce payment volumes (excluding China), according to a Bernstein Research note published in June.

Adyen’s August bombshell was its first acknowledgment that price competition was rising in the US, its second-largest market. Revenue growth in North America, which accounts for a quarter of the company’s sales, more than halved to 23% in the first half, hit mainly by Braintree’s “aggressive” pricing, according to Bernstein’s Rawat. Adyen said it hadn’t lost large customers, buts its unwillingness to join the price fight is prompting investors to envisage a rough second half.

At investor day, Adyen will have to either show that customers who had previously moved volume off its platform have switched back or take a more flexible approach to pricing, “backtracking from the hard-line stance taken on the earnings call,” Financial Technology Partners said in a published note.

Meanwhile, from a valuation of about €46 billion prior to earnings, ranking alongside Netherlands’ largest bank ING Groep NV, Adyen’s market worth has fallen to €21 billion. The co-founders collectively lost about €1.85 billion, placing them among the biggest losers of the slide.

Some investors like ARK’s exchange-traded funds and California-based WCM Investment Management doubled down and bought on the dip, while Adyen’s largest shareholder, Singaporean state investor Temasek, hung tight.

“Despite short-term turbulence from macroeconomic volatility and price-based competition,” Ark trusts the management’s long-term vision, said Andrew Kim, a research associate at the firm. Ark, which first invested in Adyen in 2019, wants the company’s management to detail “steps to achieve its long-term growth and margin targets” when it meets with investors tomorrow, he said.

But for many others, Adyen’s growth story had lost its shine. With the plunge, Adyen’s shares are now down 75% from its 2021 peak, but it still trades at about 29 times forward earnings. That’s significantly more than rival PayPal, valued at about 10 times.

The brutality of the decline has many investors pointing fingers at the company’s lack of transparency. Even after signaling a slowdown in August, Adyen reaffirmed its medium-term objective, without defining that period. Investors are now demanding that management quantify those targets or reset them. The company’s semi-annual results disclosures are also seen as inadequate, especially by US investors used to quarterly updates, Jefferies analyst Leitner said.

Adyen is listening to such concerns — it has promised to provide a third-quarter business update when it meets investors on Nov. 8. Still, while the decision to sit down with anxious investors to explain its growth plans has been welcomed, it’s not something that comes naturally to the company’s unassuming, low-profile top executives.

Earlier this year when co-CEO Van der Does wandered into the company’s crowded office cafeteria a few blocks from Amsterdam’s stock exchange, he barely drew a glance. One of the biggest shareholders of the company, the billionaire executive — dressed in jeans and a black gilet, and carrying a backpack — poured himself a glass of mint water and headed upstairs.

The problem with Adyen’s management is that “sometimes I think that they don’t want to be listed,” said Jim Tehupuring, director at Dutch wealth management firm 1Vermogensbeheer, which sold its shares in the company after the recent slump but plans to buy it again once the selling pressure subsides. “They just want to do what they’re good at.”

--With assistance from Thomas Hall.

(Adds Ark comment in 23rd paragraph.)