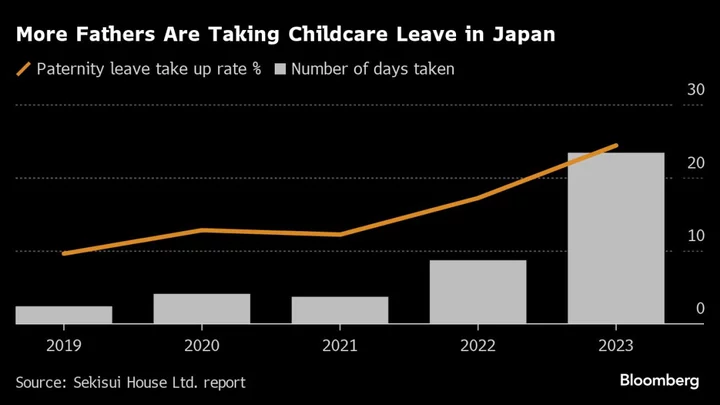

A year after revisions to Japan’s paternity leave system, the number of new fathers taking childcare leave has jumped, with one survey showing a doubling in the number of days taken off compared to last year.

Despite having one of the world’s most generous paternity leave system already before the revisions, the number of fathers actually making use of it has remained relatively low until now.

But the number of days that the average father took for paternity leave has risen to 23.4 according to a 2023 survey conducted by home builder Sekisui House Ltd., up from just 2.4 in 2019. The percentage of those who have taken paternity leave has also risen to 24.4%, up from 9.6% four years ago. The survey polled 9,400 people with children of elementary school age or younger.

A government push to encourage fathers to take childcare leave has been at least partially responsible for the jump. With revisions to the childcare law last year, fathers can be more flexible about taking leaves in batches in the eight weeks after their child’s birth, making the leave they were already entitled to more accessible.

From April, companies with at least 1,000 employees have also been required to disclose what percentage of their employees take paternity leaves. That’s added to societal pressure on companies to let fathers take time off to care for children.

Japan’s paternity leave system, which allows up to 52 weeks of paid time off, is the second most generous among countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development as of last year. In comparison, the US doesn’t have any national statutory paid paternity leave, while the average among OECD nations is 10.4 days.

Still, few men had been actually using the system due to a mixture of societal and corporate pressure.

“Employees have started to feel the change in society and corporate attitudes and have begun to feel that it’s ok to take paternity leave,” said Akiko Matsumoto, an assistant manager at Hitachi Ltd.’s diversity and inclusion division.

Last year, Hitachi began offering seminars to expecting employees that outline available childcare and other related systems, and introduced tools that can calculate workers’ likely net incomes during parental leaves.

Moves to improve paternity leave take-up rates have made some progress among other Japanese firms. Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corp. recently said it will double the amount of company-backed leave available to male employees to 20 days, until their child turns two.

“There was also a sense within the management that reaching a take-up rate of 100% when it’s only a one day leave is pointless,” said Chisa Kobuchi, a diversity and inclusion manager at the company.

Some firms are taking a further step in their approach. From August, Sekisui House launched a new system that allows parents to take leaves when their children are unable to go to school, or have a serious illness. Workers can either shorten their working hours or days, or take full leaves of up to two years.

“We were able to take this next step as we already had a culture where people can take time off through our support for parental leaves,” said Miwa Yamada, an executive officer and senior manager of Sekisui’s diversity and inclusion department.

Partly through government efforts to support women, the labor participation rate rose to 74.3% last year among working-age women. That’s 16 percentage points higher than when the childcare leave law was enacted in 1992, boosting the country’s labor market.

But while more women work, they still shoulder the bulk of housework and childcare in the country. The amount of time Japanese women spend doing housework and childcare is more than five fold the time spent by men, according to OECD data. That’s far above the 1.9 times average, and underscores how far the country remains to a more balanced division of labor.

Shungo Koreeda, a researcher at Daiwa Institute of Research, said that a culture of long work hours at Japanese companies also needs to be revised. Without a change in the environment that allows men to more effectively be part of childcare even after their leaves are over, meaningful change may be difficult to come by.

Among couples with one child where the husband doesn’t help with housework and childcare at all on his days off, only a third have a second child, according to a health ministry report published last year. That ratio goes up to more than 80% when husbands spend more than six hours on housework and childcare.

Those figures suggest that resolving Japan’s lack of gender balance in work and care provision may hold the key to solving the country’s population crisis.