Orsted A/S said it’s prepared to walk away from projects in America unless the White House guarantees more support, highlighting the myriad challenges facing wind-energy developers in the country.

The US, far behind Europe and China in the race to build offshore wind, is targeting a jump to 30 gigawatts by the end of the decade from next to nothing now. While the Biden administration has touted its landmark clean-energy subsidy program to kick-start projects, developers must ensure a large chunk of components are US-made to take full advantage of the incentives, and that’s proving hard to achieve.

“We are still upholding a real option to walk away,” Orsted Chief Executive Officer Mads Nipper said in an interview in London. “But right now, we are still working toward a final investment decision” on projects in America.

The Danish firm has had a turbulent few months, with supply-chain glitches and soaring interest rates weighing on US plans. Shares fell as much as 9.9% on Tuesday, bringing the year-to-date decline to 37%.

While offshore farms are seen as critical to ridding the US power grid of fossil fuels and avoiding the worst effects of climate change, they’re also extremely capital- and labor-intensive. In order for the industry to bring future projects to fruition, it’s “inevitable” that consumer prices for energy will increase, Nipper said.

“And if they don’t, neither we nor any of our colleagues are going to build more offshore,” Nipper said. “It’s very simple.”

It’s a tough time for offshore wind globally, with costs for steel and other materials spiraling higher just as countries push to add more turbines. Large projects by the likes of Vattenfall AB and Iberdrola SA have already been scrapped this year.

Read More: The Great US Offshore Wind-Power Boom Has Begun to Falter

Orsted’s delays were triggered by bureaucratic uncertainties during the previous US administration and were intensified by supply-chain disruptions during the Covid-19 pandemic. Biden’s push on clean energy helped accelerate some plans, but high interest rates and delays in procuring foundations, known as monopiles, for its wind turbines slowed developments even more.

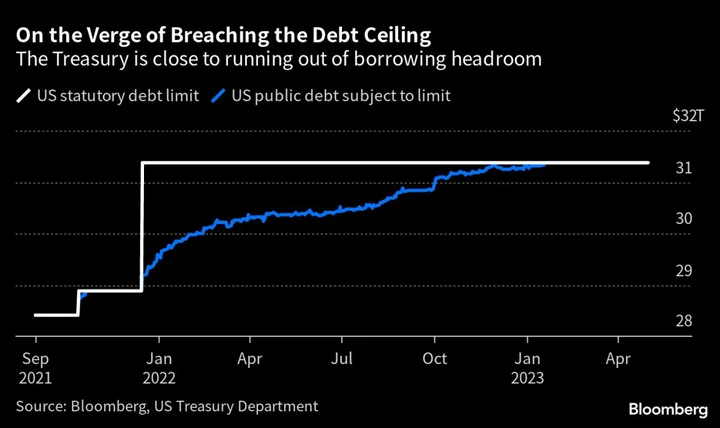

Because final investment decisions weren’t made and the projects were being funded by the company’s balance sheet, the fact that long-term interest rates in the US soared above 3% means Orsted’s cost of capital is higher.

“For a company like ours, where the targeted range of returns is 150 to 300 basis points above our cost of capital, it has essentially made this extremely tough,” Nipper said.

Nipper said Orsted couldn’t have predicted the industry turmoil, yet an investor selloff saw the company lose $8 billion in value last week after impairments were booked on several US projects. Longer-term plans also are at risk, with developments near New Jersey and Delaware not investible right now, he said.

“We have spent money essentially since 2018 and also made supplier commitments,” Nipper said. “We have also said to our investors: We will take a forward-looking view and if you consider these costs really sunk, then actually the forward-looking business case is comfortable for this portfolio of projects.”

Despite shareholder concern, the CEO said he’s had the support of the board since the stock price slumped. JPMorgan Chase & Co. says it hosted a roadshow with the firm Monday, and it highlights concern around the risk of further impairments. The bank said the profit warning was mainly company specific, but there’s a wider read-across on higher rates.

Read More: Orsted Shares Plunge as Company Warns of $2.3 Billion US Hit

Under the Inflation Reduction Act, Orsted and other developers can already tap into tax credits generally worth 30%. At issue is the ability to claim additional bonus credits under the law that reward developers for using domestic content and projects that benefit so-called energy communities, such as those with coal mines and plants.

Nipper has asked the White House to guarantee subsidies without the domestic content requirement at first and requested extra time to overcome the difficulties in sourcing American-made material. Representatives of the White House, Treasury Department and Interior Department didn’t immediately have a comment.

“What we proposed was a grace period, say, so give us three to five years,” the CEO said. “Right now, it can’t deliver.”

--With assistance from Jennifer A. Dlouhy.

(Updates 13th paragraph with more from JPMorgan note; A previous version corrected the day in fourth paragraph.)