In downtown Munich, police cars blocked roads to a modern office building where security guards patrolled the halls in a show of force that reflects Germany’s increasingly uncomfortable struggle with its violent past.

The high-level security was for the opening of a new headquarters for the Conference of European Rabbis last week, and the ceremony – close to where the Nazis embarked on their rise to power – took place as Bavaria prepares to vote after a campaign overshadowed by allegations of anti-Semitism.

Hailing the “historic” decision to locate the representative body for Jewish religious leaders in the Bavarian capital, Florian Herrmann, a member of the state’s cabinet, said the government will be “unshakable” in its protection of Jewish life. That necessity has been underscored in the run-up to the Oct. 8 regional election.

Bavarian Premier and Christian Social Union leader Markus Soeder effectively pardoned his deputy, Hubert Aiwanger, over links to a flier from the 1980s that threatened traitors to the “fatherland” with a “free flight up the chimney at Auschwitz,” the Nazi deathcamp. While acknowledging the flier’s existence, Aiwanger said he wasn’t the author, and kept his job.

Yet the lingering scandal reflects how public discourse has become increasingly divisive in Germany and once-taboo associations can be waived aside as the political landscape fragments.

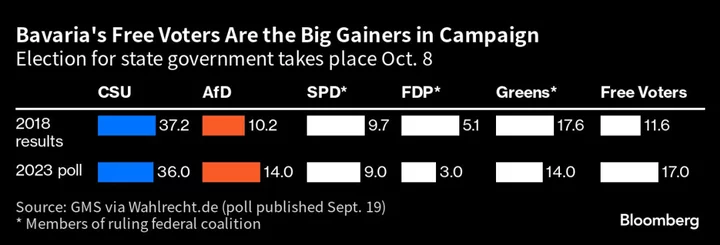

Franz-Josef Strauss, a Bavarian politician who served in West Germany’s first post-World War II cabinets, famously said that there can be no room for a legitimate party to the right of the CSU. Yet Soeder is under pressure as support for the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) climbs. What’s more, Aiwanger’s Free Voters got a lift after the 52-year-old state economy minister painted himself as the victim of a smear campaign. Emboldened, he has since gone on the attack, mainly targeting the Greens and Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s governing coalition in Berlin.

For Mirjam Zadoff, the director of Munich’s Nazi Documentation Center, the affair reflects not so much an upswell of anti-Semitism as a broader shift toward political “provocations.” While the trends are shocking in Germany because of its past, these “memory wars” are being fought across Europe, she said.

In Poland, many directors of state-run museums lost their positions under the nationalist Law & Justice government due to differences over interpreting history, as they did in Viktor Orban’s Hungary. Spain is tussling with how to characterize the fascist Franco regime, while on the eve of invading Ukraine, Russia shut the Memorial Human Rights Centre. “No country is immune to these changes,” Zadoff said.

Unlike in Berlin, where most traces of the Nazi reign of terror were long since obliterated, the evidence of that history is still very much intact in Munich, where the National Socialist German Workers’ Party made its headquarters next to the 19th century neo-classical splendor of Kӧnigsplatz.

The “Führer Building,” where Adolf Hitler maintained an office after seizing power in Berlin, is now a college for music and performing arts. The base of two “Temples of Honor” that were part of the cult of Nazi mythology stand partially overgrown on either side of the street opposite. The site of the “Brown House” – named after the Nazis’ identifying color – is occupied by Zadoff’s center.

Her organization’s role is to foster learning to help prevent racism and promote diversity and tolerance, while also asking how Erinnerungskultur – Germany’s culture of memory — can become more inclusive. “To reflect one’s violent history is crucial to a democratic discourse,” she said.

Yet, in September, the federal government ordered police raids on an extremist group that worshiped Germanic gods, describing it as “cult-like, deeply racist and anti-Semitic.” And five concentration camp memorial sites reported an increase in far-right threats and incidences of vandalism, according to Deutschlandfunk radio.

While no mainstream German political force openly questions the country’s role in the Holocaust, the recent rise in support for a nationalist party like the AfD is still shocking to many. It now regularly polls as Germany’s second most-popular party, well ahead of Scholz’s Social Democrats and the two other ruling parties.

In Bavaria, however, the AfD has been beaten back by the Free Voters, which leapfrogged the far-right party into second place in the wake of the flier affair. Soeder’s CSU, which hasn’t lost an election in Bavaria since 1950, is still in pole position, but facing its worst result since then.

Despite the adverse publicity, Aiwanger attributes his party’s popularity to its closeness to the people, with policies including pushing for an end to inheritance tax, affordable energy prices and putting agriculture and skilled trades at the heart of policymaking. “Sensible voters” recognize when “a dirty campaign” is being waged, he said in a statement.

The Free Voters, a conservative movement focused on local issues, bubbled away at the community level for years before entering the Bavarian state parliament in 2008. Aiwanger is contesting his local electoral district centered on the town of Landshut, a 45-minute train ride to the northeast of Munich. He’s likely to take the seat from the CSU and win a direct mandate for the Free Voters for the first time, according to projections by election.de.

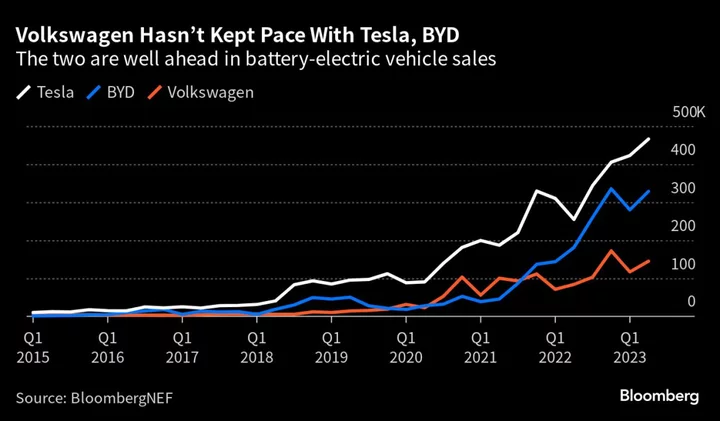

Landshut is an unlikely place for a political upset. Strung along the Isar River, it’s picture postcard pretty, with a castle overlooking an old town comprising an array of medieval houses painted in pastel shades and a mix of upscale shops. BMW employs 3,500 people at a factory there making electric motors and other components, while many residents commute to Munich, Germany’s richest city.

Despite nagging uncertainties affecting any auto town, Landshut’s outlook is healthy. It ranked in the top flight of a national “future atlas” study, suggesting locals had few reasons to search for political alternatives. Around town, there’s indeed little sign of a hotly contested campaign, with few posters and only an occasional placard of Aiwanger.

His party’s real base is in the villages and small towns of rural Lower Bavaria, according to Anna-Katharina Messmer, a sociologist at the Stiftung Neue Verantwortung think tank in Berlin who has conducted research into its appeal. Aiwanger resonates among conservatives who “embrace that he fights against ‘woke’ culture,” said Messmer, adding that his outspoken rhetoric is part of the shift in discourse that accompanied the AfD’s rise.

Still, the Free Voters are not the AfD. Aiwanger’s group favors protecting the environment and expanding renewable energy “in consultation with the people.” They’re pro-EU and share the same European umbrella group as mainstream liberal parties. They once had national aspirations, but have since largely retreated to state parliaments in Bavaria and the Rhineland — though that may change if they win big next weekend.

Economic concerns and frustration with a fractious three-way coalition in Berlin that seems incapable of digging Germany out of its malaise are the usual explanations for the febrile political atmosphere. In Germany as elsewhere, politicians are struggling how to respond to an increasingly polarized society.

Sigi Hagl, a Landshut town councilor and former leader of the Bavarian Greens, has witnessed the division between the rural communities where Aiwanger is celebrated as a local hero, and an urban population where some are concerned by the darkening atmosphere. The antagonism is especially directed against the environmental party.

“The mood is bitter, it’s aggressive, bordering on hate,” said Hagl.

Yet there do appear to be limits, as German officialdom continues its quiet work. The Bavarian state government funds a center for Jewish life from the budget of Education Minister Michael Piazolo, a Free Voters lawmaker who works with schools to promote understanding and tackle intolerance. The number of anti-Semitic incidents recorded across Germany in 2022 declined by some 11% from the previous year, albeit they remained at a high level of almost seven a day.

While no grounds for complacency, Zadoff of the Nazi Documentation Center in Munich sees Germany’s elaborate system of state-backed political education and memory culture as a bulwark against populism.

“As long it will remain in place, it’ll be much harder to persuade majorities in Germany that the best thing is now to forget the Nazi past, to forget our responsibility,” she said.

That doesn’t erase wider concerns at the coarseness seeping into the debate in Germany – ground zero for both extremism and remembrance. It’s a fight for continued relevance that’s all the more valid in the centenary year of the hyperinflation-fueled Munich Beer Hall Putsch of November 1923, which catapulted Hitler to international prominence.

“Munich remains the key to German-Jewish relations,” Chief Rabbi Pinchas Goldschmidt, president of the Conference of European Rabbis, said before he attached the traditional mezuzah to the new center’s door post. “Yes, anti-Semitism is a problem everywhere, also in Europe,” he said. “That’s why we’re here, to fight on.”

--With assistance from Jody Megson.