A possible downgrade of Italy to junk this week would be hugely symbolic, potentially consequential — and very controversial.

The unprecedented branding of a Group of Seven economy as a “substantial credit risk” could be delivered by Moody’s Investors Service, whose Baa3 rating for the country is at the lowest rung of investment grade, with a negative outlook.

Any announcement on Friday would be its first assessment since Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s coalition adopted a looser fiscal stance in September. That then caused Italy’s bond-yield spread over Germany — a key measure of risk — to widen to 210 basis points for the first time since January.

With the spread back below 190 basis points, investors aren’t generally anticipating a downgrade, not least while rivals of Moody’s are less pessimistic on the country. But that doesn’t make the upcoming diary date any less precarious.

A cut to junk would be a “shock to an already fragile market,” said Rohan Khanna, head of euro rates strategy at Barclays Plc.

He reckons a downgrade could propel the spread back toward 250 basis points — a level last seen around the snap election in 2022 that put Meloni in power. Any yield spike could heap pressure on European Central Bank officials to stem turmoil.

While some funds might exclude holding junk bonds, a single assessment could limit damage, and investors have had time to prepare. But a seismic reaction can’t be excluded: Moody’s analysts know Greece’s first downgrade to junk in 2010 — by the company now called S&P Global Ratings — escalated Europe’s sovereign debt crisis.

“They have no incentive to downgrade further,” said Zsofia Barta, an associate professor at the University of Albany and co-author of Rating Politics, a book on sovereign credit. “The last thing that rating agencies want is a kind of spiral where something spooks the market. They don’t want to be the cause of the problem.”

Moody’s could avoid publishing anything, but there’s a case to watch closely. The negative outlook was announced in August 2022. Historically, the average time a borrower can then await a change in status is about a year. And while junk is one possible outcome, so is a reprieve to a stable outlook.

Public Finances

Moody’s has highlighted three problem areas. The first two are structural reforms and challenges on energy supply, both on which Meloni’s government could claim some progress.

Public finances may be the bigger worry: specifically what Moody’s said were “risks that Italy’s fiscal strength will be further weakened by sluggish growth, higher funding costs, and potentially weaker fiscal discipline.”

On each of those items, things haven’t been stellar. Italy has just barely escaped a recession, higher ECB interest rates have stoked borrowing costs, and Meloni’s 2024 budget was described by Moody’s rival, Fitch Ratings, as a “significant loosening.”

Officials no longer foresee a primary surplus next year, where revenues exceed spending before interest costs, and the deficit won’t return to the European Union’s 3% limit until 2026.

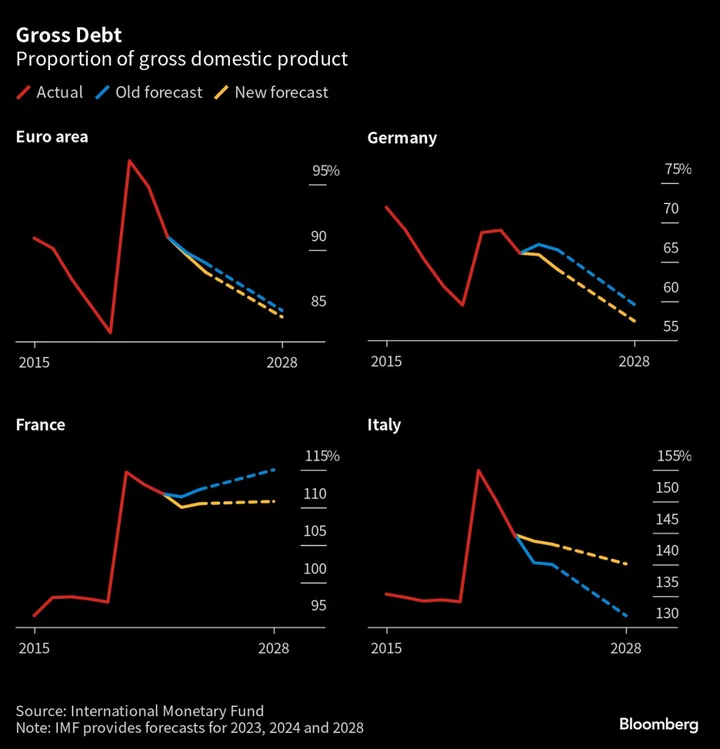

Moody’s tends to focus on debt as a percentage of gross domestic product. Italy’s will still exceed 140% of output in five years, according to International Monetary Fund forecasts last month — more than 8 percentage points higher than it predicted in April.

“The easy part for Italy to bring down the debt-to-GDP ratio is behind us, said Dario Messi, fixed income strategist at Julius Baer. “There are still major challenges ahead.”

It’s significant though that Moody’s has a noticeably more pessimistic view than its rivals. Both Fitch and S&P rate Italy one notch higher, with stable outlooks. A drop to junk would put an unusual gap between them.

“I would think it very unlikely that Moody’s would want to do this, and particularly to do it on its own,” Barta said. “They are very much the outlier right now.”

Cutting Italy to junk could also look awkward in comparison with other G-7 economies. Its debt ratio is far lower than the 255% of GDP of Japan, which Moody’s assesses several notches higher. The UK and France have even better ratings, but debt ratios noticeably above 100% — and fiscal blemishes of their own.

Unlike Britain, whose former premier Liz Truss unveiled unfunded tax cuts that caused a market backlash in 2022, Italy hasn’t so brazenly tested investors. Meanwhile the country has had more success than France in raising its pension age to aid the sustainability of its retirement system.

But unlike Italy, both the UK and Japan have the flexibility of their own currency. That’s where the ECB’s role will matter — Frankfurt officials have prepared a crisis tool to stem turmoil, though one that would require the Italian government to submit to external policy requirements.

Such help could be called for if Moody’s does cut. The fact that few investors seem to anticipate a downgrade would amplify subsequent volatility.

“I don’t think anybody’s expecting them to go to junk,” said David Zahn, head of European fixed income at Franklin Templeton, who is underweight Italian bonds. “It’s not like Italy’s going to default, it’s not like Italy’s going to leave the euro. It’s more: is that 200bps priced correctly? I would say no.”

With its borrowing costs around their highest for more than a decade, a downgrade would inevitably prompt a renewed discussion over its ability to meet its debt obligations.

“The market would not like it,” said Messi at Julius Baer. “It brings back the question about debt sustainability — even more prominently than already now.”

--With assistance from Yuko Takeo and Chiara Albanese.