Giorgia Meloni’s government is confronting drastically worsening budget figures, adding pressure to her options on how to bolster finances.

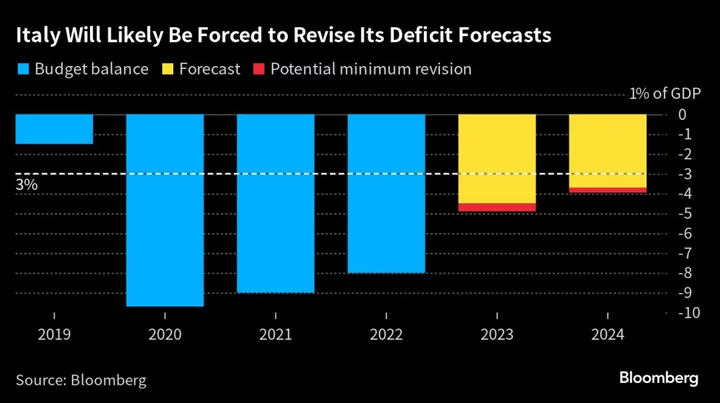

A much larger 2023 shortfall close to 5% of output — as measured on an underlying basis without one-off factors from accounting revisions — is inevitable given weakened economic growth and electoral promises including tax cuts, according to people familiar with the matter, who declined to be identified because the numbers are still being discussed. The prior target was 4.5%.

Lower than expected growth and the cost of some electoral promises is set to also affect next year’s deficit forecast, which could be widened to closer to 4% from the current 3.7% projection, the people said adding that numbers are still being discussed and a final decision has not been made. The Economy Ministry declined a request for comment.

The issue was discussed at a coalition meeting late Wednesday, at which Finance Minister Giancarlo Giorgetti, who will be responsible for writing the budget law, was a notable absent.

The spread between Italian and German government bond yields, a common measure of risk, rose to around 174 basis points after the Bloomberg report, and was at 175 basis points Thursday, close to the highest since July. Still, the measure has been remarkably stable this year, facilitating Meloni’s ability to manage the country’s finances.

A wider deficit would add pressure on her government to sell state-owned companies to boost finances. Her government is considering the sale of Monte Paschi — and other selected state-owned assets — as a way to allow Italy’s far-right coalition to fund new spending without adding to the country’s mammoth debt.

This year’s number may look even bigger once the effects of a change in accounting treatment for housing renovation incentives, known as the superbonus, are factored in.

Meloni is seeking to square the generous electoral pledges of her three-party right-wing coalition with the need to keep Italy’s mammoth debt on a sustainable path as European Union deficit limits kick in.

“The next 2024 draft budget law will become an even more important test for the compliance of the current government with fiscal discipline,” JP Morgan analyst Marco Protopapa said in a report Tuesday. “The additional shortage of resources for flagship measures may intensify political noise in the next few weeks.”

Protopapa’s own projection, including the “superbonus” effect, is for a 2023 deficit of as much as 6.5%.

While Italy isn’t currently subject to EU fiscal rules, because the suspension of the so-called Stability and Growth pact is still in place, next year is another story.

That regime featuring a limit on deficits of 3% of gross domestic product will return in 2024, and countries have yet to agree on how a new framework for interpreting such limits to take into account country-specific issues.

That will present Meloni with a challenge as she balances the need to keep public finances on a stable footing against the prior electoral promises of her Brothers of Italy party and its coalition partners, Matteo Salvini’s League and Forza Italia, currently led by Antonio Tajani.

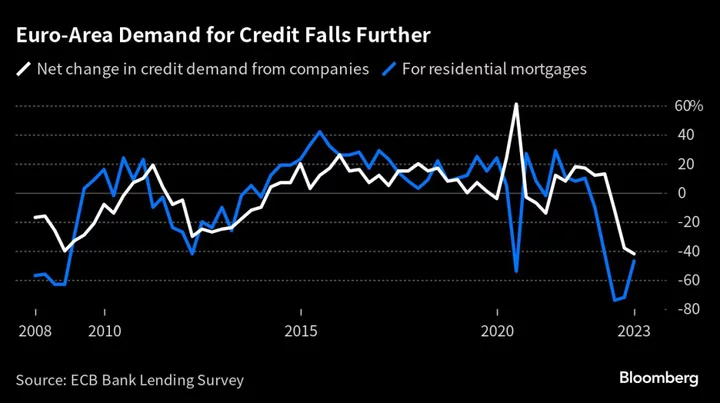

Italy’s poor growth performance isn’t helping. Expansion was 0.6% in the first three months of this year, but the economy then shrank 0.4% in the period from April to June.

Output for the remainder of the year doesn’t look strong, with economists predicting 0.1% increases in the third and fourth quarters as the country struggles with rising interest rates, weakening global export demand and economic difficulties in key partners like Germany.

That said, the government is hoping to keep its growth targets for the year around 1%, Giorgetti said Sunday.

--With assistance from Giovanni Salzano, James Hirai, Giulia Morpurgo and John Follain.

(Updates with markets, outcome of coalition meeting from fourth paragraph)