Emmanuel Macron is beefing up France’s arsenal of strategic tools to protect vulnerable firms against foreign buyers with deep pockets, with a particular eye on the US and China.

The government will soon set in stone tighter rules on takeovers by non-European Union investors, the Finance Ministry told Bloomberg. The threshold for triggering a review will be lowered and the number of protected areas extended to include critical raw materials, as well as French units of foreign companies.

Also under discussion is a more aggressive approach that could see state-backed funds acquire tech abroad, and even in the US, according to one French official.

Some officials argue for punchier checks on investments more closely modeled on the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), and government-backed vehicles with the heft to step in and buy strategic assets.

France has long pushed for an assertive European industrial policy. The pandemic, Russia’s war against Ukraine and Joe Biden’s massive green subsidies program gave that drive new impetus. Paris has looked to those challenges as reasons to use state muscle to protect key industries from what is seen as unfair competition from allies like the US and from potentially hostile players like China.

Higher interest rates in a country where firms rely mainly on bank credit and debt financing, combined with a manufacturing and services slump, and a weaker euro, have prompted concerns within Macron’s administration that stretched suppliers — especially in energy and defense — are vulnerable to foreign companies with bigger war chests. French business failures have also risen sharply as Covid-crisis support measures are withdrawn.

“The big issue is the lack of deep-pocketed investors in Europe who can step in,” said Sarah Guillou, an economist at the OFCE think-tank.

US companies have been building up firepower. Cash holdings among S&P 500 Index members reached a two-year high at almost $2.4 trillion in the second quarter, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. US private equity and venture capital dry powder totals some $1.8 trillion.

Opposition French lawmaker Olivier Marleix, who leads the conservative Republicains in France’s lower house, accused the government of being inconsistent and urged a firm approach.

“The threats of predation are increasingly significant, coming from every foreign power, including China and the US, and the government needs to adopt a clear stance and a clear doctrine,” he told Bloomberg.

To be sure, the Finance Ministry flexed its muscles last month when it scuppered a deal between a US and a Canadian firm in the name of defense and energy sovereignty, preventing French submarine and nuclear reactor suppliers from changing hands.

Read more: Germany Moves to Shield Key Companies From Foreign Takeovers

That came in the context of a difficult transatlantic relationship, with Macron irking US officials earlier this year with calls for Europe to carve its own policy as a counterweight to the US and China. On top of that are French-backed efforts to claw back money through digital and carbon taxes.

The challenges of competition between allies were also highlighted two weeks ago when EU and US negotiators failed to reach a trade agreement on steel and aluminum to avoid a return of tariffs.

Since Macron became president in 2017, his government has derailed a merger between French and Italian automakers Renault SA and Fiat SpA, as well as the proposed takeover of grocery chain Carrefour SA by Canada’s Alimentation Couche-Tard Inc. It also blocked the acquisition of tech company Photonis by US firm Teledyne in 2020.

Inspired by CFIUS, a US interagency group led by the Department of the Treasury that reviews mergers and acquisitions for national security concerns, France has strengthened checks, adding energy, chips and food to its list of strategic industries.

The French Treasury has examined more investment projects in recent years after lowering screening thresholds to 10% of voting rights and expanding reasons for refusing projects. Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire said 325 dossiers were put under the microscope last year, up from 137 in 2017.

One official advocated boosting the muscle of France’s interministerial Strategic Information and Economic Security Department, which receives alerts from individuals and companies that consider French know-how to be in danger.

It also hears from researchers and universities. One person familiar with the screening process said China has switched its focus to faculties and scientists to gain access to intelligence and technologies, given the hurdles to takeovers.

China’s outbound acquisitions have dropped substantially, partly because economic woes at home have led companies to review overseas portfolios to optimize returns, but also due to foreign scrutiny. Yet the country has kept its appetite for health care, tech and chip sectors they see as strategic.

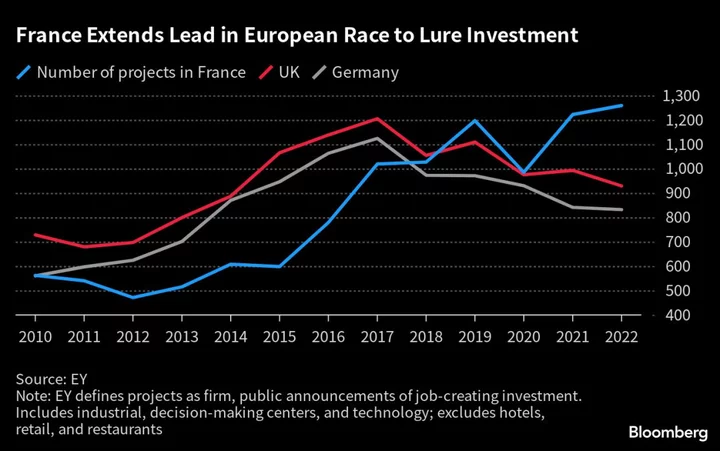

Macron faces the challenge of balancing his pledge to safeguard sovereignty with an economic agenda that promises to encourage foreign investors choosing France.

“All governments want to attract foreign capital because it’s a source of wealth, and at the same time they would like to pick and choose which investors are allowed in,” the OFCE’s Guillou added.

One way to stand out in the global technology race could be to boost state-backed funds such as the €200 million ($211 million) Innovation Defense Fund, one official said. Bpifrance, which runs the fund, didn’t return requests for comment.

Still, for now the focus remains protecting French assets. The latest dilemma for Macron is whether to prevent ailing tech company Atos SE from falling into the hands of Czech energy billionaire Daniel Kretinsky.

--With assistance from Alberto Nardelli, Alison Williams, Andrew Silverman, Benoit Berthelot, Neil Sipes, Paul Gulberg and Vinicy Chan.