Every driver in London, as of Tuesday, is now subject to strict pollution rules, completing one of the world’s most ambitious vehicle emissions policies and taking the British capital closer to having healthy air.

While the final expansion of the ULEZ, or ultra low emissions zone, is only a continuation of clean air charges that have been tightening since 2008 — under Boris Johnson when he was mayor of London and now his successor Sadiq Khan — this last phase has been the most controversial. That’s because the £12.50 ($15.72) per day levy for most non-compliant vehicles now hits those living in outer boroughs of London, where people tend to be more car dependent and have lower incomes.

The ULEZ expansion wasn’t even guaranteed until July when London’s High Court ruled against Conservative-led local authorities who had sued over the plans to grow the zone.

Read More: London’s Secret Fix for Air Pollution: Making Drivers Pay Up

The pollution charges particularly target older diesel vehicles, which tend to create more harmful concentrations of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) in the air than petrol because of the differences in the way the fuel is combusted. For Khan, the battle to tackle these emissions has been worth it. As a sufferer of adult onset asthma, he’s made London’s air quality a personal mission. And while some political opponents think the mayor has gone too far with the ULEZ, others say he isn’t doing enough to reduce traffic smog.

In order to get a sense of the likely impact of the latest ULEZ expansion, it helps to look at the ways transport and pollution in the city have already changed since the previous phase was rolled out four years ago. Here’s what to expect from London’s newest clampdown on tailpipe emissions and the influence it’s having on clean air policies worldwide.

‘Magic’ guidelines

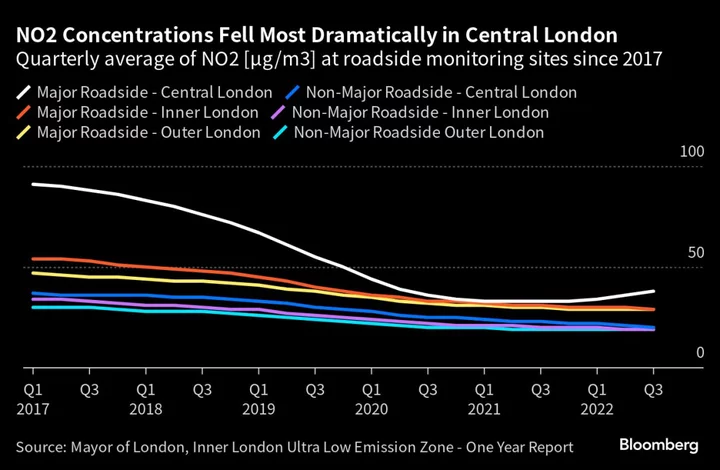

A decade ago London had NO2 levels that were among the worst of major world cities, and that has improved dramatically alongside the expansion of the ULEZ. At its most severe, NO2 can lead to reduced lung development and respiratory infections in children and breathing difficulties in early adulthood, as well as premature death.

The decline in NO2 pollution seen since 2017 can’t just be attributed to ULEZ. Internal combustion engine cars, both diesel and petrol, have become much cleaner over time as standards have tightened. There are more affordable electric vehicles on the market and buses and taxis have also become less emitting.

The benefit to London’s outer-borough residents, which have the highest number of deaths linked to air pollution, has been used by Khan as a major argument for its expansion. Analysis released by the mayor’s office in June suggests that, based on analysis of income, education, crime levels and other factors, poorer Londoners and those from immigrant communities are more likely to live in areas with worse air quality.

Yet even with the expanded ULEZ, no Londoners will live in areas that meet the tougher new World Heath Organization’s annual average guidelines of 10 micrograms per cubic meter of air for NO2 or 5 micrograms per cubic meter of air for PM2.5, which are fine particles emitted by cars, industry and other harmful sources.

“I don’t think the expansion of ULEZ will be sufficient in the longer term,” said Frank Kelly, a professor at Imperial College London who has worked on air pollution science for 30 years. “Even though it’s had a big impact in central and inner London, the concentrations of pollutants still are too high. So other measures will need to be introduced in due course if we’re going to get down to those magic WHO guidelines.”

‘Hammering down on diesel’

Simon Birkett, who founded the campaign Clean Air in London, said he’d like to see the next mayor take things a step further and completely ban diesel vehicles on the city’s roads. But already sales of new diesel cars in London have been declining, he noted, falling to about 5,400 in 2022, from a peak of almost 69,000 in 2016. “The ULEZ has been hammering down on diesel,” Birkett said.

At the same time, London has seen a huge growth in the number of electric vehicles on the roads, from less than 3,000 registered a decade ago to almost 75,000 by the first quarter of this year.

The drivers most likely to be stung by the ULEZ expansion are commercial van owners. Unlike cars, the van market is still dominated by diesel — more than 90% of vans are diesel-fueled. Data suggests that just under half of vans registered to addresses in the outer boroughs of the city are not ULEZ compliant, though the mayor’s office disputes the relevance of this data, arguing that many of those vehicles are not actually driven in London. It uses data collected from road-monitoring cameras, which suggests 80% of vans are ULEZ compliant.

Some small business groups have raised opposition to an extra charge on vans, citing the financial burdens this can create for their business. In response to concerns, Khan expanded a vehicle scrappage scheme, once only available to a limited number of recipients, to all drivers of non-compliant vehicles. Still, this only covers those people living in London and not those on the borders who may need to commute into the capital daily.

The scheme offers £2,000 ($2,515) for a car driver to scrap a non-compliant vehicle, or £7,000 ($8,804) for a van. The scrappage grant is worth even more if drivers opt to take a voucher for public transport as part of the payment. During the previous phase of the scheme, introduced two years ago, some 15,000 cars, vans and motorcycles were scrapped.

One of the biggest arguments against the ULEZ expansion has been that new areas brought into its scope have poorer public transport options than central London, where the policy started. People in outer London are less likely to live within walking distance of a bus stop or train station. In areas with less access to public transport, people are more likely to have a car.

In response, Khan is also pledging more funds for public transport, paid for by any fines charged under the ULEZ scheme. This includes a bus “Superloop,” which promises travel for £1.75 around outer London. The full network has yet to be introduced and consultations are still ongoing.

Toxic politics

While previous ULEZ phases were rolled out without much controversy, this final expansion into the suburbs has become politically toxic, potentially costing Khan’s Labour Party the chance to win Johnson’s former parliamentary seat in the outer London borough of Uxbridge in July.

That loss has split Khan and Labour leader Keir Starmer, who in July said the mayor should “reflect” on the ULEZ after the election defeat and said the country needed to find a new way of tackling transport pollution. It also prompted Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak to try to capitalize on the division, declaring he’s “on the side of motorists,” launching a review of pollution cutting policies, such as low traffic neighborhoods and 20 mile-per-hour speed limit zones.

While the mayor’s office claims that nine in 10 drivers will comply with the new rules, that figure has been contested. Like the van data, this figure comes from traffic cameras, whereas Bloomberg’s analysis of Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency data found that at least 15% of cars licensed in outer London will not be compliant with ULEZ.

Read More: Why London’s ULEZ Emissions Charge Became a Political Football

Valuable lessons

Now the largest in the world, the progress of London’s pollution charging zone has been watched by mayors from Bogota to Montreal, who’ve been inspired to introduce their own control districts for vehicle emissions.

“London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone has been a reference for Bogota’s air quality agenda,” Claudia Lopez, the mayor of Bogota, said in 2021. Montreal’s mayor Valerie Plante, who is laying the groundwork for a low-emission strategy in her city, has also highlighted ULEZ’s achievements.

Meanwhile, Giuseppe Sala, mayor of Milan, said in a recent Guardian article that he’s been particularly impressed by the measures designed to ease the burdens of ULEZ’s expansion – from the scrappage scheme to public transport investment – as he seeks to curb his city’s traffic problems.

To be sure, all cities have their own unique vehicle pollution concerns, but Birkett said London has at least provided real data on what actions can work at scale.

“While diesel is a particularly serious problem in Europe, that requires large, strong ultra low emission zones, ULEZ expansion in London has valuable lessons for other cities around the world,” he said.

--With assistance from Mathieu Dion and Jack Ryan.