A sense of gloom is settling over Ukraine as the failure of a months-long counteroffensive gives way to the second winter since the Russian invasion.

A fierce snowstorm cut power to thousands across southern Ukraine over the weekend, while temperatures in the east, where fighting is fierce, have plunged well below freezing. In the Ukrainian public, polls show cracks emerging and a softening in President Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s approval rating.

The longer nights coincide with mounting frustration over the stalled advance and tension among government and military leaders spilling into the open. As NATO ministers meet in Brussels, there are signs that help from the military alliance is wavering.

Once-confident predictions of victory over Kremlin troops are being replaced by a grim awareness that the war is most likely to grind on.

“I feel desperate,” said Nataliya Kobyuk, 34, a nurse in Kyiv whose husband has been on the frontline since the invasion began 22 months ago. “Compared to last year, now it’s more difficult — there’s no end to this war, and sometimes I simply stop believing it will ever end.”

Zelenskiy knows that the battlefield fatigue extends to hearts and minds. The wartime leader, who maintains his nightly television addresses as a conduit to the public and a way to lift spirits, recognizes the need to address a weary public’s concerns on what comes next, according to people familiar with this thinking.

“It is important that people understand that what is in their hearts is being seen and the changes that are needed will be made,” Zelenskiy said in an address earlier this month after a Russian missile strike killed 19 soldiers at an award ceremony in southeastern Ukraine. The president called for an investigation into the circumstances of exposing personnel to attack.

The mood has seeped into Zelenskiy’s support. Still lofty at 76%, his approval rating has dropped from a wartime high of 91%, according to the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology.

Volodymyr Paniotto, the head of KIIS, sees the spike in the president’s approval as normal for a war environment, just as the ensuing drop when the initial wave of patriotism fades. Another survey showed that as of May last year, 68% of Ukrainians felt that disagreements should be put aside in war — a figure that’s now fallen to 25%.

“The rally-around-the-flag effect is ending,” Paniotto said in an interview.

Read More: Ukraine’s Struggle for Arms and Attention Gives Putin an Opening

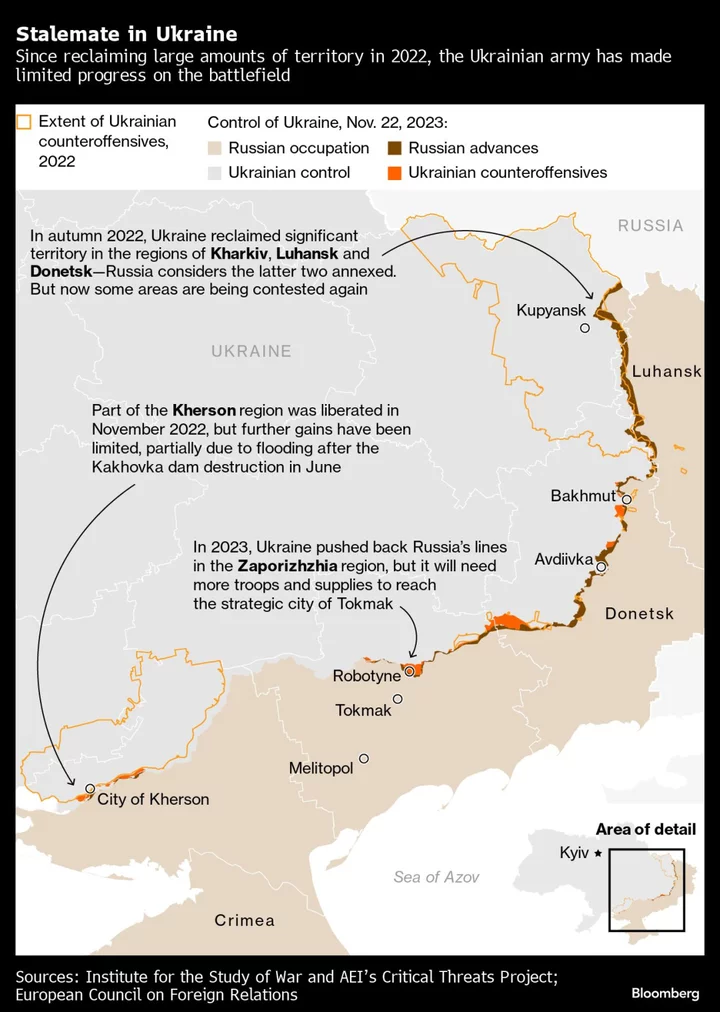

The sobering outlook contrasts with a far more optimistic view a year ago. By December 2022, Ukrainian forces, partly spurred on as Russian troops withdrew and redeployed, had seized back territory around Kyiv, in the Kharkiv region in the northeast and Kherson in the south to the Dnipro River — and generated the sense that this year’s counteroffensive could do more.

But the campaign, which began in June, failed to penetrate entrenched Russian lines stretching from the Donbas region in the east to the mouth of the Dnipro on the Black Sea. The 260 square kilometers (100 square miles) of territory reclaimed in the counteroffensive in 2023 amounts to less than 1% of land that was retaken last year.

Reversing the tide in the summer, when Kyiv military officials were hinting at a breakthrough in the southern region of Zaporizhzhia, Russian troops are now advancing toward Ukrainian-occupied Avdiivka in the east. A defeat there would only spell more gloom.

Add to that anxiety over conscription as manpower at the front is squeezed and perennial anger over corruption, an issue still at the top of the list of Ukrainian complaints, and the winter months look even bleaker.

Marianna Tkalych, a professor of psychology in charge of social research center Rating Lab, attributes the “overheated expectations” around the counteroffensive to the darkening mood.

“It is very de-motivating,” Tkalych said. “On one hand, we have this irritation and disappointment — and on the other hand, people still choose to fight as a coping strategy, so resilience is strong.”

But on the world stage, Ukraine’s plight has gotten more complicated. Zelenskiy’s efforts to win allies outside the Western fold as a way to corner Vladimir Putin into talks has been upended by the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war. A meeting last month in Malta to push forward Kyiv’s blueprint for peace was distracted by the conflict in the Middle East.

The Ukrainian leader said in mid-November that the shift in focus had slowed deliveries of desperately needed artillery shells, further undermining the counteroffensive. Meanwhile, the until-now rejected notion of territorial concessions for peace is gaining ground among a small number of Ukrainians.

Ukraine will be high on the agenda when foreign ministers from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization gather on Tuesday and Wednesday, with allies likely to reiterate their support despite concerns that aid is starting to wane. NATO will seek to showcase Ukraine’s progress toward joining, but a formal invitation still remains a lofty goal as long as the war continues.

For people on the ground, what lies ahead is anticipation of another barrage of missile and drone strikes aiming to tear into the country’s energy system. Russia fired its biggest barrage of loitering munitions to date over the weekend, though Ukraine’s air defense said it shot down 74 of 75 Shahed-131/136 drones, most of which targeted the Kyiv region.

National grid operator NPC Ukrenergo has sounded a warning on a jump in demand for heating, urging citizens to save energy by using table lamps instead of ceiling lights, running laundry at night and avoiding simultaneous use of home appliances.

Serhiy Petrovskiy, a 52-year old designer and media consultant from Lviv, agreed that expectations for the counteroffensive were “a little overstated.”

“Now the biggest fear is internal chaos and strife,” he said. “People are afraid that all this may deprive the country of Western support, which is a key issue for now.”

--With assistance from Daryna Krasnolutska, Demetrios Pogkas and Natalia Drozdiak.

Author: Olesia Safronova, Kateryna Chursina and Volodymyr Verbianyi