Almost 10 million Iranians have slipped into poverty from a combination of sanctions, bad economic management and volatile international oil prices during a “lost decade” of growth, according to a World Bank report.

The report is the institution’s first official assessment of poverty in the country of 85 million people since the 1979 Islamic revolution. It portrays an economy in which inequality and poverty surged in the decade through 2020, with US-led policies contributing to that, and women bearing the brunt of the impact of both sanctions and the Covid-19 pandemic.

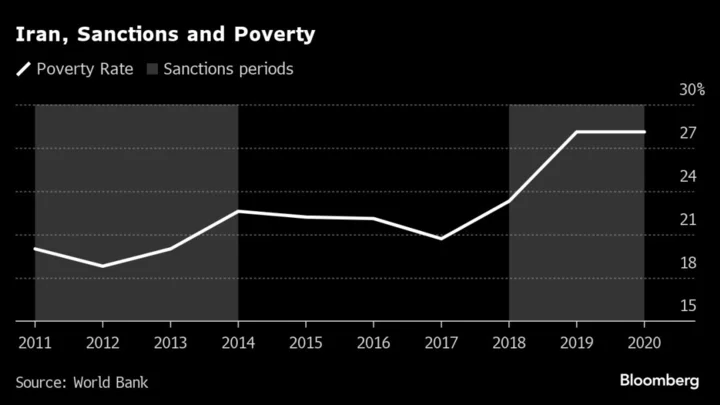

Iran saw declining poverty in the decades leading up to the 2011 imposition of sanctions by then-President Barack Obama, with those falling below the global poverty line going from 40% of the population in 1980 to around 20% in the early 2000s.

But since 2011, the “on-again, off-again sanctions” — which were imposed by the US and other countries — have had “a deleterious impact” on economic growth and Iranians’ welfare, the report’s authors wrote. “Iran’s economy has suffered from a lost decade of economic growth.”

Economic woes in Iran were among the drivers of last year’s mass protests, which were sparked by the death of a young woman detained for allegedly violating strict Islamic dress codes.

The government in Tehran has taken advantage of a diplomatic thaw with the US this summer to increase its oil production and exports – a key source of foreign currency. Tehran says output will rise further, although Washington has vowed to clamp down on shipments.

The bank’s researchers weren’t able to travel to Iran for the report, which was released Nov. 15 without publicity and touches on issues politically sensitive to both Washington — the impact of sanctions — and Tehran — the prevalence of poverty. The US Treasury Department didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, an Iranian-born economist at Virginia Tech who wasn’t involved in the report, said the World Bank’s publication was significant given the often politically fraught relations that the government in Tehran has had with the Washington-based bank since the 1979 revolution.

Many influential hard-liners in Iran see the bank as an advocate of a Western system of market-driven capitalism that they oppose, he said, and even reformers have been cautious about working with the bank in the past.

Poverty Line

The household survey data, which was collected by the Iranian government, showed that between 2011 and 2020 the number of people in Iran below the World Bank’s poverty line for upper-middle-income countries — $6.85 per day, in purchasing power parity terms — increased from 20% to 28.1% of the population. That difference equates to 9.5 million additional people in poverty, the World Bank calculated.

The bulk of that increase came after President Donald Trump in 2018 pulled the US out of a nuclear deal with Iran and reimposed sanctions.

Periods of poverty gains and losses during the decade were “broadly aligned with the cycle of sanctions imposed, relaxed, and reimposed,” the World Bank said.

The report added, however, that “the drivers of poverty are far more complex,” pointing to Iran’s over-dependence on oil revenues, which is subject to swings in international prices, high inflation and cash payments to the poor that aren’t indexed to inflation.

As well, the World Bank pointed out that even during periods without sanctions, economic growth was non-inclusive and didn’t benefit the bottom 40% of the population.

According to the bank, Iran’s per-capita gross domestic product had contracted by 0.6 percentage points per year over the decade after sanctions were first introduced. By some calculations, the World Bank estimated, Iran’s real GDP has grown by as much as 19 percentage points less in certain years than it would have without sanctions.

“Iran is one of the worst performers among its peers,” the authors wrote. In 2011 it was the eighth least-poor country, among 25 upper-middle-income countries. In 2020 it had fallen to 17th.

Impact on Women

Women, the World Bank said, had been disproportionately affected both by the 2018 resumption of sanctions and the Covid-19 pandemic, with female-headed households already more likely to be poor than those headed by males.

According to the bank’s report, the number of women working had risen from 11% in 2011 to 14% in 2018, “which translates to about a million more women finding jobs.”

“Yet the reimposition of sanctions and the onset of Covid-19 wiped out many of those gains,” the report’s authors wrote.

Besides the 28% already in poverty, a further 40% of Iran’s population was at risk of falling into poverty in the next two years, the World Bank said.

The authors also highlighted that the country’s poverty is becoming more intractable. In 2011, it would have taken an injection of 5.2% of the value of their consumption to pull them above the poverty line. That figure had risen to 8.2% by 2020.

Virginia Tech’s Salehi-Isfahani said the bank’s report documented a trend in rising poverty that he and a number of economists had been tracking for years, though he said the bank’s calculations may have overstated the number of Iranians in poverty.

By his calculations, based on the same government household survey data used by the World Bank, the ranks of the poor in Iran have actually gone down in the past two years thanks to government cash transfers, he said.

In an interview, Salehi-Isfahani said there was no doubt that US sanctions imposed as a result of Tehran’s own foreign policy choices had been the predominant driver of a significant increase in poverty in Iran.

“In the case of Iran, it is a very straightforward story,” Salehi-Isfahani said. “Poverty was falling until 2011 then began rising. Why did that happen? There’s only one valid answer and that’s sanctions.”

--With assistance from Patrick Sykes.