United Airlines presents itself as the unrivaled leader in cleaner jet fuel. A recent ad campaign featuring the garbage-can-dwelling Oscar the Grouch as the airline’s new “chief trash officer” publicizes its commitment to turn banana peels and old socks into less-polluting jet fuel. In another ad, the company says it’s “investing in more sustainable aviation fuel production than any other airline in the world.”

Chicago-based United Airlines Holdings Inc., like the rest of the aviation industry, is grappling with its enormous climate impact. United expects to burn more than 4 billion gallons of jet fuel this year, which will spout about 40 million tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere—more than double the pollution of all the cars in the company’s home state of Illinois.

Global aviation generates 2.5% of man-made CO2, and it’s one of the industries that can’t be rapidly electrified. As the planet-warming pollution from driving vehicles and running power plants declines, the carbon toll of flying is only expected to rise. By 2050 aviation could exceed 20% of humanity’s total carbon footprint.

That’s why airlines have focused on slashing emissions by dramatically increasing the use of sustainable aviation fuel, or SAF, made from things such as used cooking oil, animal fat and agriculture waste. Planes powered by these petroleum alternatives release far fewer heat-trapping emissions than those using fossil fuel.

Only a half-dozen companies make commercial quantities of SAF, which accounts for about 0.1% of the world’s jet-fuel supply and costs at least twice as much to produce. Almost every major airline has pledged to use at least 10% sustainable jet fuel by 2030. For most, including United, this would amount to a hundredfold increase in only seven years.

United has publicly embraced the enormity of the challenge. In an interview, Chief Executive Officer Scott Kirby sounds almost like an environmental activist at times, describing himself as an “admitted climate change geek going all the way back to college.” He’s concerned that the public still doesn’t fully grasp the looming dangers of our warming planet and says airlines must play a “leading role” to help solve the crisis.

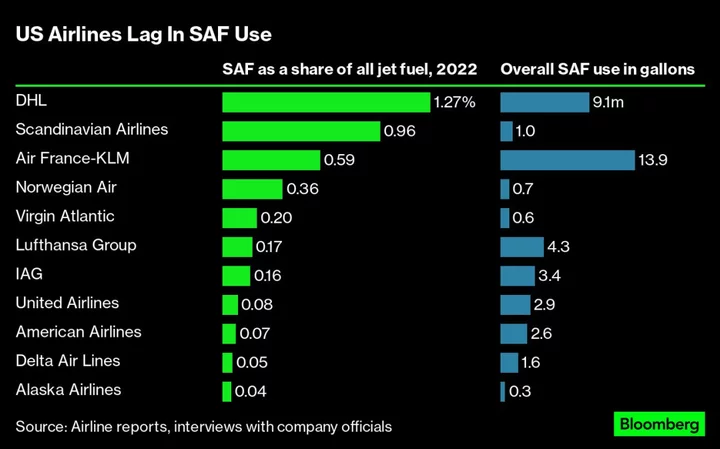

But United’s leadership in sustainable fuels hasn’t matched its rhetoric. United consumed 2.9 million gallons of SAF last year, representing 0.08% of its fuel supply. That puts the company slightly ahead of its US counterparts but far behind several airlines in Europe, which have to prepare to meet new requirements that don’t exist in the US.

Air France-KLM has more than quadrupled United’s total by using 13.9 million gallons of SAF, making it the world leader by volume. That amounted to 0.59% of its fuel consumption, or more than seven times United’s percentage.

The lackluster performance in the US shines a spotlight on starkly different approaches to spurring SAF around the world. European Union rules will require 2% SAF usage by 2025, 20% by 2035, and 70% by 2050. Governments in the UK and Japan have proposed similar rules. Many European airlines, including Air France-KLM, have supported the EU regulatory approach. Australia’s biggest carrier, Qantas Airways Ltd., recently called on the government to introduce its own requirements “to help kick-start local production of SAF.”

United and other US carriers, though, have staunchly opposed any such mandates on their home turf, arguing that the airlines are already voluntarily pursuing sustainable fuels and that requiring their use before adequate supplies exist will cause prices to soar. “We don’t want flying to become a luxury commodity,” says Helen Giles, managing director of environmental sustainability at Southwest Airlines Co.

Regulators in California are considering including jet fuel under the state’s low-carbon fuel standard, which could force airlines to use more SAF or potentially pay penalties. Airlines for America, the trade group representing US airlines, has criticized the idea, warning the state that it’s overstepping its authority. United’s Kirby is the group’s vice chairman.

Instead of mandates, Kirby argues, governments need to pour financial incentives into the space, much the way they did for wind and solar over the past couple of decades. “Today it’s cheaper to produce a megawatt of electricity with wind and solar than it is with fossil fuels,” he says. “I believe the same thing can and will happen in SAF if we invest in it.”

Although generous tax credits certainly helped spur wind and solar, so have mandates: About half of all growth in US clean electricity since 2000 is linked to state laws requiring that electric utilities get a certain share of their power from renewable sources, according to a recent report from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Kirby says United’s attempts to build the market are more significant than simply counting its SAF usage. The centerpiece of these efforts is a $75 million investment in a sustainable flight fund, which has put money into a half-dozen clean-fuel startups.

That certainly eclipses the investments of other big US airlines. But $75 million adds up to less than 1% of United’s annual jet-fuel bill. And this amount is unlikely to move the needle much for SAF developers, who often need a half-billion dollars to build a plant. To put this in broader perspective, McKinsey & Co. estimates that the world needs to invest about $175 billion a year—mostly on developing new sustainable fuels—if airlines are going to achieve their midcentury climate targets.

Critics contend that United and other US airlines, by balking at higher prices for cleaner fuels and lobbying against mandates, are standing in the way of meaningful progress on SAF. “It’s disappointing to see this kind of greenwashing from United Airlines and Airlines for America,” says Nik Pavlenko, program lead for fuels at the nonprofit International Council on Clean Transportation.

A decade ago, United took a bolder approach to sustainable jet fuel. Some of the airline’s impact is visible at a century-old refinery in Paramount, a suburb of 50,000 people just outside Los Angeles.

On a scorching August afternoon, with the nearby San Gabriel Mountains cloaked in haze, a dense web of steel pipes, tubes, scaffolding and towers thrums with life. This refinery, owned by Boston-based biofuels producer World Energy LLC, was the sole maker of SAF in the US for the past seven years. Its first domestic competitor came online in May.

Instead of petroleum, the refinery is fed by oven-black rail cars full of animal fat with the consistency of Crisco. The shipments come from slaughterhouses across the US, Canada and Australia. Most of the fat is converted into renewable diesel for trucks. Each year the refinery also churns out about 8 million gallons of jet fuel for use at Los Angeles International Airport and other nearby facilities.

World Energy’s SAF produces less than half of the greenhouse gases of conventional options. And it exists, in part, thanks to United’s help. In 2013 the airline inked a novel agreement with the refinery. Details of the deal have never been publicly disclosed, but three people familiar with the transaction say the airline agreed to pay a slight premium compared with conventional jet fuel for a three-year supply when the refinery eventually came online. More important, it included a risky “warm idle clause,” which meant United would continue to pay the biofuels producer even if it had to stop delivering because of high feedstock costs or other reasons.

Guaranteed cash flow made the project more attractive to financial backers. United also shared in the refinery’s upside. If the fuel could fetch a higher price than the airline would pay (which it eventually did), the producer could sell it elsewhere—and split the premiums with United.

“United has been absolutely critical in getting SAF off the ground,” says Gene Gebolys, World Energy’s CEO, who declined to discuss the deal’s terms. “They moved when others wouldn’t.”

It’s exactly the type of deal that most airlines are unwilling to make today. When United signed a second contract with World Energy in 2019, the airline announced it would purchase as much as 10 million gallons over the next two years. This time, though, the company shouldered none of the refinery’s risks and ultimately purchased less than 20% of the publicized amount. (United officials noted the huge drop in fuel usage during the Covid-19 pandemic.)

United and other airlines began trumpeting enormous deals for the future supply of sustainable fuels, even when their plans lacked substance. Two years ago, for instance, United unveiled what it called “the largest publicly announced SAF agreement in aviation history” by committing to purchase 1.5 billion gallons over two decades from Alder Renewables, a clean-fuels startup. Alder rebranded its business in July to showcase a broader range of renewable products it hopes to make beyond just SAF; and Darren Fuller, the company’s chief commercial officer, downplayed the United deal in an interview, calling it “a little bit of a hangover from our previous management.” (After Bloomberg Green sought comment on this from United, Alder officials sent a written statement with a different tone that said they were excited to eventually provide sustainable fuel to the airline.)

Plenty of airlines have uncorked similarly frothy deals. JetBlue Airways Corp., for instance, celebrated a deal two years ago to buy 670 million gallons of SAF at a price competitive with traditional jet fuel. The airline claimed to be well ahead of its 2030 targets. “We are well past the point of vague climate commitments,” declared JetBlue CEO Robin Hayes.

This miraculous supply of affordable SAF was supposed to begin arriving this year. But JetBlue’s deal was with a startup that had only a few employees and no facility to produce fuel. The airline quietly pulled the plug a year later, mentioning deep in an unrelated press release that the arrangement had been “terminated.” JetBlue didn’t respond to multiple interview requests.

Persuading airlines to pay the higher cost for SAF remains a central challenge. Aemetis Inc. is attempting to build a 90-million-gallon-a-year plant at an old army ammunition plant about 100 miles east of San Francisco. It plans to use waste from nearby almond orchards to help make the lower-carbon fuels, which could be used to power trucks or airplanes.

But Aemetis needs to raise a half-billion dollars to build the plant, which it calls Carbon Zero 1. That’s a tall order, even for the publicly traded Aemetis, which generates about $250 million a year, mainly selling biofuels for road transportation. To show investors there’s demand for lower-carbon jet fuel, Aemetis two years ago invited airlines to negotiate for the plant’s future fuel supply.

Despite all the airline pledges to use vast quantities of SAF, the discussions were hard. Airlines are notoriously tight-fisted when it comes to fuel, which accounts for about one-third of their operating costs. “There’s zero appetite to be one penny per gallon less competitive,” says Aemetis CEO Eric McAfee.

The biofuels company eventually persuaded at least eight airlines, including American Airlines, Qantas and Japan Airlines Co., to pay a slight premium—10% above the future price of conventional jet fuel—for about half the plant’s expected output. Conspicuously absent from the flurry of Aemetis announcements: United. Negotiations with the company faltered, McAfee says, because United wouldn’t pay a higher price for the cleaner fuel: “They’d only buy it if it were at, or lower than, the cost of conventional jet fuel.”

United officials said in a statement that the airline conducted diligence on the biofuels company and “determined that it wasn’t the right fit for us.”

All of this raises a fundamental question about who should foot the bill for decarbonizing air travel.

United’s chief argues that the public shouldn’t expect companies to pay a premium for climate-friendly products. “The blunt answer is, companies, individuals and governments are not going to buy green products unless they’re cost-competitive. They’re not,” Kirby says. “This is coming from someone that really wants to make a difference on climate change.”

But if airlines are unwilling to pay more for cleaner fuels, it thrusts the responsibility onto the public, primarily through government incentives. This, in effect, would lead to all taxpayers subsidizing the wealthiest, who fly the most. In the US, adults in households earning more than $150,000 fly more than five times as often as those in households making less than $50,000, according to a 2018 survey by Airlines for America.

It’s a different story in Europe, where airlines are already absorbing this added cost—and passing it along to travelers. Air France-KLM, for instance, adds a surcharge of €1 to €24 ($1 to $25) to all flights departing from France and the Netherlands to help cover the extra cost of SAF. The airline said it expects the added expense to total €100 million this year and says it could reach €1 billion by the end of the decade if costs don’t drop.

Sitting at a long conference table inside World Energy’s offices alongside the Paramount refinery, Gebolys relishes this topic. He’s working to expand the facility to produce dramatically more SAF—at a hefty cost of $2.5 billion—and seems to have largely turned the page on airlines spurring the market for cleaner jet fuel. Instead, he exuberantly outlines his vision of selling decarbonization directly to corporations, such as tech giants and consulting firms. These companies have goals to reach net-zero emissions, but they must somehow address their sizable climate footprints from corporate travel.

“The real market is for decarbonized flight,” Gebolys says. He’s referring to a nascent market where companies such as Microsoft Corp. and Deloitte that book a lot of corporate travel buy certificates that represent a certain quantity of sustainable jet fuel. This payment helps cover the cost premium of SAF, which makes it competitive with conventional jet fuel and spurs producers such as World Energy to deliver more of it into the market. The buyer of the certificates then takes credit for that cleaner jet fuel—and applies the carbon savings to its own footprint.

Microsoft recently announced a 10-year deal to purchase SAF certificates from World Energy representing 44 million gallons of SAF, which will allow the tech company to trim its reported emissions by almost a half-million tons over the next decade. This could be a creative way to drive more demand, but it’s unclear how many corporate buyers will step up to pay the hefty premiums. Morgan Stanley reported SAF certificates will likely cost “hundreds if not thousands of dollars” for each ton of CO2 they remove from a buyer’s footprint. (To put this in perspective, many carbon offsets sell for $5 to $10 per ton, though their impact is often dubious.)

For SAF to really take off, airlines will have to match their rhetoric with action. But this would require airlines in the US to face down what Darrin Morgan, former director of sustainable aviation fuels at Boeing Co., describes as an industrywide risk most aren’t set up to recognize.

“This isn’t just about getting the cheapest fuel,” says Morgan, now head of growth and investment at SkyNRG, an Amsterdam-based SAF developer. “This is about accomplishing something that’s existentially important to our business.”

(Corrects Scandinavian Airlines’ SAF percentage due to the company’s erroneous report in the first chart, and removes mention of them as a market leader in the 8th paragraph.)