The muck from incessant rain sloshes around Nestor N’Guessan’s feet as he points to a plot of cocoa trees ravaged by rot on his farm in Ivory Coast.

The 52-year-old grower can’t save those plants from black pod disease, so he’s focusing efforts on quarantining whatever healthy ones he has left. The soakings of recent months mean fewer pods on his trees, with some supporting just a handful of cocoa buds.

“I had to create a boundary to prevent the rest of the plantation from being contaminated,” he said while pruning the healthy thicket. “Yields are low. The weather hasn’t helped us.”

It’s a climate crisis playing out across Ivory Coast and Ghana, the heavyweights of cocoa, with consequences for global food inflation and the cost-of-living squeeze. Too much rain is lowering output and delaying harvests, with the resulting shortfall catapulting wholesale prices in New York to their highest in 46 years.

The total precipitation in West Africa since the rainy season started May 1 has been more than double the 30-year average, according to Maxar Technologies Inc. The damage to yields is compounded by growers’ long struggle over pay, leaving them little money to pour back into their plots.

This is the main harvest period, and the constant deluge turns dirt roads into impassable swamps, knocks flowers off before they bud and fosters breeding of a fungal infection that turns rugby ball-sized pods into black mush.

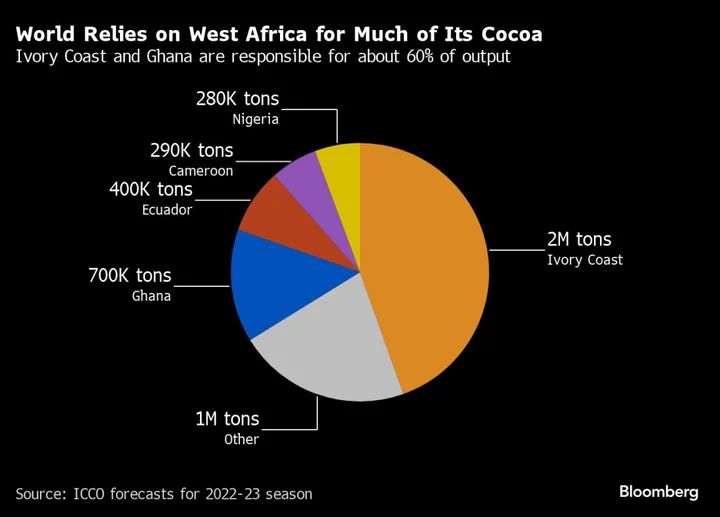

Ghana’s output is expected to be the lowest in 13 years, and Ivory Coast’s the smallest in seven, based on totals provided by traders and exporters. Together, the countries produce about 60% of the world’s beans, according to the International Cocoa Organization.

The most-active futures are trading at the highest since 1977 in New York, soaring past $4,200 a ton. At that price, you could buy about 50 barrels of oil.

“This is a bull market, and it hasn’t peaked yet,” said Fuad Mohammed Abubakar, head of government-affiliated Ghana Cocoa Marketing Co. (UK) Ltd., which sells and exports premium cocoa. “More risks lie ahead.”

With sugar also reaching a decade high, consumers likely will spend more for their chocolate bars, cookies and hot cocoa as Christmas approaches. The US Department of Agriculture forecasts prices for sugar and sweets rising 8.9% this year and another 5.6% next year, outpacing total food inflation.

Citing higher supply costs, Mondelez International Inc., maker of Toblerone bars and Oreo cookies, will raise some prices next year, Chief Executive Officer Dirk Van de Put told Bloomberg Television on Nov. 6. Nestle SA, owner of Haagen-Dazs ice cream and Quality Street candies, said it will do the same.

It would be logical to conclude that farmers benefit from the bounty, but in reality they’re not — even with the $400-a-ton premium tacked onto the market price as the living income differential.

The cocoa markets in Ivory Coast and Ghana are strictly controlled by the governments, and regulators typically sell beans to foreign buyers at least 12 months in advance.

That means the money being paid to farmers for this season’s crop was locked in about a year ago, when futures were about $2,500 a ton.

“At current farmgate prices, farmers aren’t incentivized to go into the farms,” said Mahmoud Khayat, senior trader at Ivory Cocoa Products, a bean processing company. “If prices were high, he would swim to get the cocoa.”

Right now, growers are waiting on the government’s negotiations for next season with top buyers such as Barry Callebaut AG, Cargill Inc. and Olam International Ltd. The sides are in a standoff, with the companies holding off purchases because they want a discount, according to people familiar with the matter.

Typically, there would be a push to plant more seedlings to capitalize on the boom, but many growers are prisoners to the rain and can’t afford to hire more hands, use more fertilizer or buy the necessary chemicals to ward off black pod.

The soil on Samuel Addo’s 12-acre plot in Suhum district, Ghana — about 65 kilometers (40 miles) north of the capital, Accra — has a sandy consistency, making it a bit more difficult to grow cocoa even in the best conditions.

After a heavy downpour, nearly every tree sprouted a pod that was either rotting or turning black. The only way to tame the spread is for Addo to spray his buds, called cherelles, every two weeks, but that expense is out of reach.

“It’s never attacked my farm this bad since I started farming cocoa,” Addo, 52, said. “What I’m earning is not enough to invest back into the farm.”

The El Nino weather pattern could trigger more hardship ahead as dry conditions typically set in across West Africa. Global output hasn’t met demand for the past two seasons, and it’s expected to stay that way for several more years, Abubakar said.

“The supply response will not be instant,” he said. “It will take time for higher prices to boost production.”

Plus, deforestation regulations coming from the European Union — a major hub for West Africa's crop — are likely to escalate costs as beans are tracked through the supply chain.

At this time of the year, processing plants in San Pedro, Ivory Coast’s main export hub, should be running at full tilt to clean, fumigate and pack the beans into 65-kilogram (143-pound) jute bags ready for shipment.

Yet total port arrivals in the season that started Oct. 1 total 479,449 tons, compared with an estimated 707,200 tons a year ago. That’s a 32% drop.

The dearth of supply forced Societe Ivoirienne de Transformation de Produits Agricoles, which can process more than 1,500 tons a day, to idle one of its machines the day a Bloomberg reporter visited.

The exporter is receiving about 20 cargo trucks daily, compared with about 24-26 trucks a year ago. The artery to the cocoa basket — a rugged road to begin with — is now pocked by holes brimming with rainwater, making the journey even more treacherous.

The National Federation of Dockers, which represents workers in Ivory Coast’s main ports, said this season has been abnormal. During a recent week, it counted 29 trucks in San Pedro and 32 in Abidjan, compared with 70 and 61, respectively, a year earlier.

“The flow of cocoa harvest arrivals is very low,” the federation said in an email. “Members who are usually very busy unloading cocoa bags from trucks have been redeployed to other jobs.”

The challenging climate and low pay are prompting some farmers to give up their beans in favor of other commodities, notably rubber and gold.

N’Guessan’s farm in Soubre, Ivory Coast’s cocoa heartland, is about a seven-hour drive from Abidjan. In recent years, vast rubber plantations sprung up around him to satisfy demand for tires, hoses and other products.

Rubber trees need less maintenance, and Ivory Coast is now the top producer in Africa.

“Many planters have abandoned cocoa,” he said.

In Ghana, the lure is gold. Artisanal mining accounts for about a third of the country’s output, and farmers talk about companies persistently offering them large sums of money to give up their land.

A ride through the nation’s cocoa belt finds many plantations replaced by what are known locally as galamsey.

“There is a myth that cocoa farms are often sitting on gold-rich stones,” grower Michael Acheampong said, looking at the mine next door. “Some farmers cannot resist the allure of quick money.”

The Cote d’Ivoire-Ghana Cocoa Initiative was created by both nations to dim that luster. The cartel’s purpose is to raise prices paid to farmers, saying they haven’t covered the costs of production or guaranteed a living wage for decades, Executive Secretary Alex Assanvo said.

“If farmers see high prices today and a lower price is given to them, how do we see farmers continue growing cocoa?” he said.

--With assistance from Megan Durisin Albery.

Author: Mumbi Gitau, Baudelaire Mieu and Ekow Dontoh