There’s a saying in the working class Roman neighborhood where Giorgia Meloni grew up that means “the heart is always right.” According to people close to her, that’s also a guiding principle for the Italian prime minister: she follows her gut, trusts virtually no one and takes her decisions alone.

Those qualities were on display when she split with her long-time partner last month after he became a political liability. An emotional post on social media included a warning shot to “those who hoped to weaken me by striking me in my private life.”

Her what-you-see-is-what-you-get authenticity dovetails with a steeliness that just over a year ago catapulted her into power — a position no woman has ever held in Italy. In a country where, famously, many governments collapse after a year, few thought she would last. But Meloni is used to people underestimating her.

“When she was elected, everyone feared a fascist leader, and it took a few months to realize that no, she is definitely not a fascist,” said Nathalie Tocci, director of think tank Iai.

Indeed, it’s clear that the far-right label applied to Meloni for most of her career is too simplistic for a politician who has demonstrated her flexibility and pragmatism. She’s going to need all that if some of the darker forecasts for the Italian economy prove right over the next 12 months with investors on high alert for any further hits to the budget and the yield on Italy’s 10-year bonds near the highest in a decade.

For decades Meloni bided her time, enduring the casual chauvinism of male politicians who didn’t take her seriously until it was too late. She’s had her share of missteps, but it’s clear the 46-year-old has boxed in rivals, stealthily consolidated power and reshaped the center-right almost entirely in her nationalist image. That puts her on course to become the most influential Italian politician since Silvio Berlusconi.

When Meloni served as a junior minister in Berlusconi’s last government, he patronizingly referred to her as the “little one.” Now his party Forza Italia is a minor partner in her coalition.

In conversations with senior officials there is one point they all agree on — Meloni has the last word on every dossier, from corporate deals to foreign policy. It’s her fingerprints on the strategic appointments in public companies like Enel SpA, on the decision to take a stake in Telecom Italia SpA’s network business or whether to back out of an investment pact with China.

Her reliance on a particularly tight group of confidantes is both a source of strength and her biggest weakness. On the one hand, she’s more insulated from the Machiavellian intrigue of Italian politics that has hurt rivals like Matteo Salvini, a junior coalition partner who for years looked set to become prime minister.

The flip side is that her modus operandi has resulted in careless mistakes.

There was the fight with France over migrant rescue boats that set her off on the wrong foot with Emmanuel Macron. There was the blunder over a bank tax that sent markets crashing. Then she was tricked into talking frankly about the growing fatigue with support for Ukraine in a phone call with Russian pranksters.

That Nov. 1 leak showed how unforgiving she can be when things go wrong. Her top diplomatic advisor was fired.

Within her group of confidantes, there’s an even tighter circle she considers essentially family. Among them is her personal assistant, Patrizia Scurti, who Meloni affectionately describes as “my boss” and who has been keeping her diary for almost 20 years.

Then there is her brother-in-law, who was put in charge of an agriculture ministry rebranded as “food sovereignty.” Not since Benito Mussolini have two relatives served in the same executive. Francesco Lollobrigida, a relative of the 1950s icon Gina Lollobrigida, adds a dash of Dolce Vita glamor. He is married to Meloni’s older sister, Arianna, but he has known Giorgia for longer.

They first when they met in their 20s in Rome at the local branch of Youth Front, a far-right party that has since disbanded and serves as a reminder of her own ideological origins. He is one of the few people Meloni really listens to, according to several officials close to her. Decisions approved at the formal cabinet meetings in Rome often start off as ideas batted around at family lunches with “Lollo,” as Meloni calls him.

The inner circle is fiercely protective of the prime minister.

In the days after her sister’s breakup, Arianna was trailed by a pack of reporters doggedly asking how Giorgia was coping. “How do you think she’s doing?” she snapped back, putting on her tricolor scooter helmet and climbing onto the back of a Vespa. “You are not journalists, you are gossips. But this only brings us more support.”

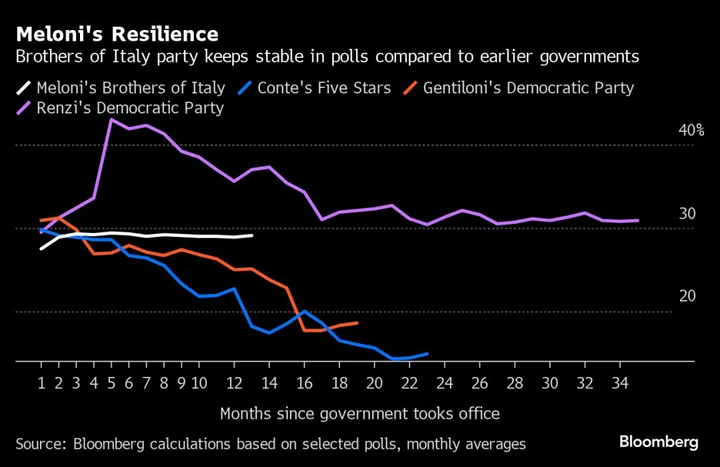

Indeed, the polls bear that out.

Dumping popular TV anchor Andrea Giambruno, the father of her daughter, resonated with the Italian public and rather tellingly drew into the mix Marina Berlusconi, arguably the second most powerful woman in Italy. Berlusconi was rumored to have played an underhand role in the controversy because a recording of Giambruno’s lewd comments was aired on the Berlusconi family’s Mediaset SpA network.

“The only thing that is true is I respect Giorgia Meloni a lot,” Berlusconi told journalist Bruno Vespa in his book. “I find her capable, coherent, concrete. I like her on the political level and I also like her a lot as a woman, even more so over the last few days.”

As she looks ahead to hosting the Group of Seven next year, Meloni has also built a network of international allies of all political persuasions. She hasn’t hitched her wagon to Donald Trump ahead of 2024 elections but instead has carefully and methodically built a rapport with US President Joe Biden.

It speaks to an inherent pragmatism, a quality various diplomats and officials have picked up. Yes, they say, she can play simpatico with Hungary’s Viktor Orban, the bete noire of the European Union, and stay up late at a summit in Granada, Spain, chatting migration with Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki. But she’s also a realist.

A UK diplomat, speaking on condition of anonymity, noted how Meloni had successfully moved away from incendiary rhetoric on migration toward more a more measured solution-driven approach. Evidence of that was European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen accepting her invitation to the island of Lampedusa, where thousands of migrants arrive every summer.

The two women, by all accounts, get on well. Von der Leyen is quick to respond to Meloni’s calls and Italy will be an important vote if the German is going lock in a second term at the head of the EU’s executive arm.

Now seen as punching above her weight in Brussels, Meloni’s days of euroskepticism are largely behind her because she’s realized that she needs the EU.

Meloni has even managed to get over that rough start to relations with Macron. She is now seen as a pragmatic leader by French officials rather than the far-right radical they had thought they would be dealing with. The relationship has deepened, according to one person familiar with their discussions, who mentioned regular exchanges between the two leaders and their mutual respect on migration. They are now texting regularly, said another.

The economic situation also remains under control for now. Italy has dodged a recession, the European Central Bank has paused its interest rate hikes and rating agencies have held off on downgrading government bonds.

But there’s one more policy maker that Meloni forged a surprising relationship with — her predecessor as prime minister, Mario Draghi. Draghi spent most of his career as an economist and won plaudits for steering Europe through the debt crisis as president of the ECB and he offers a sobering assessment of the outlook for Meloni and Europe’s other leaders. Draghi is predicting that the European economy will be in recession by the end of the year.

--With assistance from Alex Wickham, Giovanni Salzano, Ania Nussbaum and Samy Adghirni.