Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

Germany’s economy — Europe’s largest — is struggling to grow, and the weakness is set to persist.

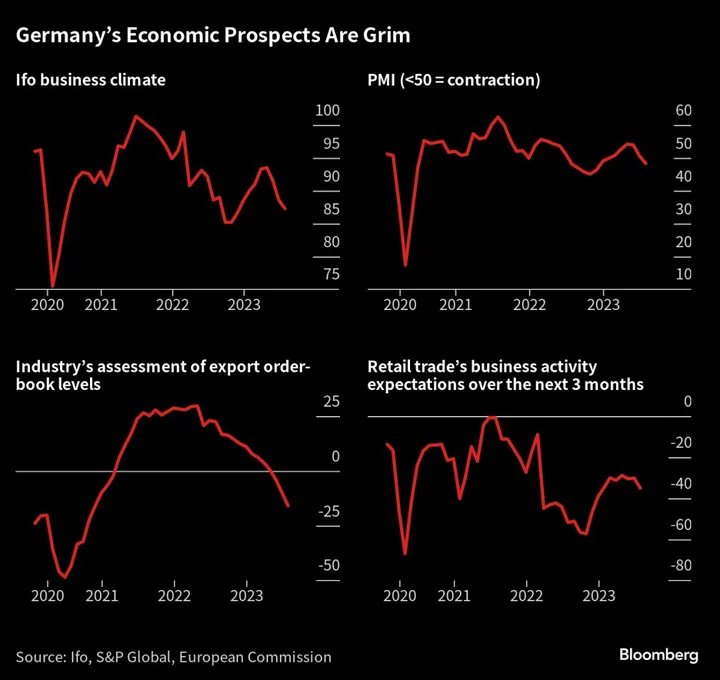

News this week that expansion failed to resume during the past quarter, coupled with poor survey readings for July, showcase how the country long seen as the region’s motor of expansion is currently a brake on its outlook.

The recession that Germany has now barely exited already defied a bold prediction by Chancellor Olaf Scholz in January that such a slump “absolutely” wouldn’t materialize.

Its latest near-miss highlights how deep-seated industrial malaise is enduring in a year when the International Monetary Fund forecasts the energy-hobbled economy faces the only contraction of the Group of Seven nations. Could Germany be reverting to its onetime role as a dead weight on Europe’s growth potential?

“Whether the economy is creeping along, or contracting slightly, I think is a second-order problem,” said Thomas Mayer, founder of the Flossbach von Storch Research Institute and a long-standing economic observer of the country. “I think Germany is competing for the title of the ‘Sick Man of Europe.’”

Such a label was commonly slapped on Germany in the years after reunification in 1990, as that laborious process of stitching two nations together sapped the economy of its postwar dynamism and bred stubbornly high unemployment.

The slog lasted well into this century, as witnessed in a remarkable period when Italy’s annual expansion outpaced its bigger and richer peer for more than half a decade.

This time round, Germany’s persisting energy crisis stemming from the war in Ukraine is crippling manufacturers in an economy already struggling with a demographically induced skills shortage and poor productivity. Meanwhile intensified global competition in electric vehicles threatens its carmaking prowess.

Such longer-term challenges are combining with weak Chinese demand and tighter monetary policy to further squeeze industry. Another quarter-point interest-rate hike by the European Central Bank this past week to tame inflation will heap more pressure there.

While the full-year contraction of 0.3% anticipated for Germany by both the IMF and the Bundesbank for this year isn’t huge, it’s meaningful: the last time the economy shrank while Italy’s grew was in 2003.

“Under-performance is not just a prediction — we’re already seeing that,” Joerg Kraemer, chief economist at Commerzbank AG, said before the latest GDP data. “We forecast a renewed recession for the second half of the year.”

The numbers on Friday showed that the economy escaped another quarter of contraction —but only just, even if the prior drop in gross domestic product was smaller than previously estimated.

Clemens Fuest, president of the Munich-based Ifo Institute, even reckoned this week that the recession had continued, citing more manufacturing-led deterioration in his organization’s longstanding monthly business survey released on Tuesday.

A day earlier, S&P Global’s purchasing manager index showed industrial weakness was marked enough to outweigh continuing services expansion. As the region’s dominant economy, that means Germany is pulling the rest down.

“General conditions remain poor, and leading indicators do not point to significant momentum in the second half of the year either,” said Helaba Chief Economist Gertrud Traud. “Stagnation is not optimistic — it’s not a euphoric number.”

It’s not all gloom. Unemployment at 5.7% remains within a percentage point of its all-time low, and that isn’t likely to change much in data due on Tuesday — a robust labor market that is sustaining consumers at a time of high inflation.

Arne Freundt, chief executive officer of Puma SE, this week cited “stable demand” in Germany for his company’s sneakers and apparel. Volkswagen AG Chief Financial Officer Arno Antlitz was similarly sanguine.

“There’s a certain uncertainty on the side of the customers in terms of inflation, but I personally don’t expect a recession in the next quarters,” he told Bloomberg Television.

Germany’s industrial woes and poor growth performance at present don’t really distinguish it from its regional peers either, not least because they share many of the same problems.

In Italy, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni keenly tweeted this week that the IMF’s 2023 predictions show faster expansion there than in Germany and France, momentum that reflects a delayed pandemic rebound, including a tourist boom, as well as European Union-fueled spending.

But manufacturers in the euro zone’s third-biggest economy are also languishing, and its population squeeze is even more alarming. Italy has been most frequently labeled Europe’s “sick man” in past years.

Germany’s enduring headache of how to produce affordable energy — a result of its longstanding reliance on Russian gas and its politically fueled abhorrence of nuclear power — remains a standout challenge however, just as it attempts to quicken a shift away from fossil fuels.

The economy’s focus on churning out gasoline-guzzling cars while rivals ramp up electric vehicle production is another problem, and Volkswagen’s experience of lower Chinese orders was partly behind a cut in its sales outlook on Thursday.

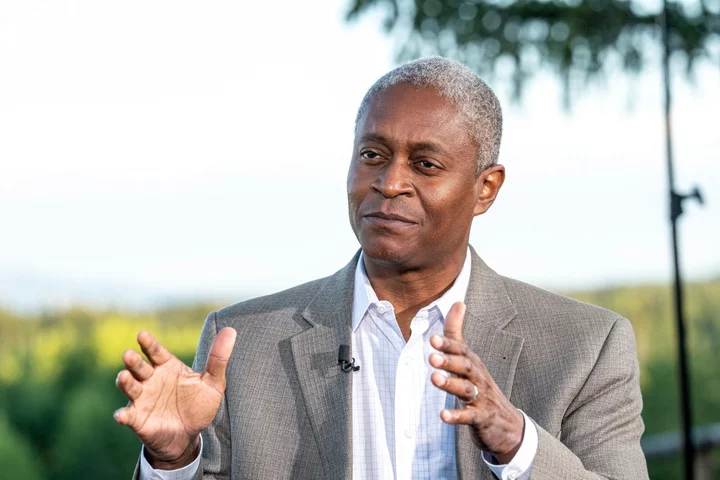

David Folkerts-Landau, chief economist at Deutsche Bank AG, reckons that’s the thin end of the wedge.

“The Germans in particular, because of a large manufacturing sector, are falling very much behind the US, because the technological gap is getting wider and wider,” he told Bloomberg Television last month, adding that other US government subsidy plans will reinforce that lag.

Fixing the future is a primary concern for Scholz and his advisers, who have attributed the rise of the far-right Alternative for Germany to mounting fears about long-term growth prospects. An opinion poll published on July 23 put the party’s support at a record 22%.

Their primary solution for now is to throw money at the problem, offering subsidies to companies willing to open factories. The latest measure revealed last week is for a €20 billion ($22 billion) giveaway to bolster semiconductor manufacturing and shore up the country’s technology sector.

That’s a focus on big corporate spending, but the longstanding backbone of German prosperity is the so-called Mittelstand — a nationwide fabric of smaller, often family-owned enterprises, whose specialized products have long provided the foundation of its export strength.

Kraemer of Commerzbank reckons that’s where to look for signs of how Germany’s fate as a major economy will be determined.

“The good, many medium-sized companies that are well capitalized, that have solid balance sheets, and their employees, who are hard-working and enjoy working here — that is the hope,” he said.

--With assistance from Francine Lacqua, Manus Cranny, Oliver Crook and Anna Edwards.