A year after President Emmanuel Macron received a warning that France’s credit status faced closer scrutiny, the possibility of a humbling downgrade is looming ever larger.

With debt stuck around 110% of gross domestic product, the criteria S&P Global Ratings specified to keep its AA assessment are being tested. It has scheduled an update on Friday, almost exactly 12 months after announcing a negative outlook.

Data on the eve of that showed French output unexpectedly shrank in the third quarter, and a downgrade could inflict a further body blow to the presidency of Macron, who has held to commitments for economic reform and fiscal rectitude since taking office in 2017.

That approach initially convinced sovereign analysts — until unprecedented spending during the pandemic and the energy crisis left France with bloated public finances.

So now, more than a decade after S&P was first to lower its top assessment in the wake of the euro-region’s debt turmoil, France’s status as a borrower is once again in question. A cut would follow in the footsteps of Fitch Ratings, which downgraded one notch lower to AA- in April.

“France is a weak AA rating, no doubt,” said Axel Botte, head of market strategy at Ostrum Asset Management. He sees single A as a “likely” outcome over the medium term.

Any change would give investors more fuel to re-evaluate Europe’s fiscal landscape, as they reward Ireland, Portugal and Greece for cutting debt at a time when France has dragged its feet.

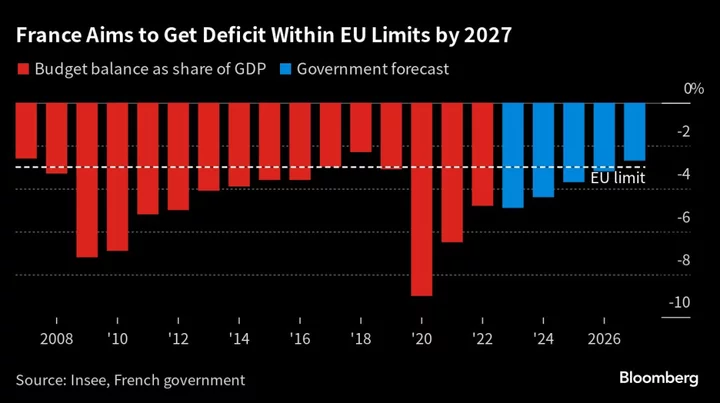

Economists expect little fiscal consolidation next year, and the government only intends to bring the budget gap within the European Union’s newly-reinstated 3%-of-output limit by 2027.

Much of that plan relies on a forecast for an acceleration in economic growth, but the latest indicators show the country may instead be losing momentum. Consumer spending dropped in October and November survey data confirmed on Friday that manufacturing activity suffered a 10th consecutive month of contraction.

The concern is that France’s debt pile — 20 percentage points higher than the bloc’s 90% average — exposes it to interest rates that have markedly risen. The French 10-year bond yield, which traded below 0% less than two years ago, has soared past 3%.

According to finance ministry forecasts, the public-debt ratio will be stable through 2025, as the deficit narrows only gradually.

That may look challenging against the timetable of S&P, whose negative outlooks for investment-grade borrowers tend to focus on a two-year horizon.

It said in June that “we could lower our sovereign ratings on France within the next 18 months if general government debt as a share of GDP does not steadily decline over 2023-2025.”

Ministry officials anticipate the costs of servicing those borrowings will nearly double to €74 billion ($81 billion) by 2027.

The gap between the 10-year French yield and the German benchmark has widened to about 60 basis over the past year, a contrast to the equivalent Italian spread which has narrowed. Spain’s spread over Germany has been stable over that period.

“Overall debt is seen as a longer term risk on France, and you need a premium for this,” said Olivier De Larouziere, chief investment officer for global fixed income at BNP Paribas Asset Management. “I think this is exactly why the spread has widened.”

The rating danger has put Macron’s team on the defensive. Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire has said there’s no reason to doubt his or France’s credibility, and warned that a downgrade would only amplify the country’s challenges by pushing borrowing costs up further.

“Everything is possible, it’s up to them,” he said Thursday in a broadcast interview. “But I think we have provided solid arguments on our determination to cut debt.”

The euro area’s second-biggest economy does remain safely in investment-grade territory. Moody’s Investors Service, whose rating of France is comparable to S&P’s, has kept its outlook stable. It assesses Italy far lower, just one notch above junk.

Moreover, refinancing risk will only emerge if rates remain high for “a very long time,” De Larouziere said. Good liquidity also underpins the appeal of its bonds, he added.

In September, France presented a first step toward tackling high debt with €16 billion of savings to reduce deficit to 4.4% of economic output in 2024 from 4.9% this year. But most of that will come from withdrawing vast support provided to households and firms during the energy crisis.

Those fiscal plans face closer scrutiny after the EU said last month that France is at risk of breaching recommendations on spending growth next year.

Ministers have pledged to intensify efforts to cut outlays in 2025. The government is also mulling a reboot of Macron’s trademark economic overhauls with plans to simplify the business environment and possible changes to unemployment benefits to encourage people into work.

Whether that’s enough to convince S&P hangs in the balance. What’s for sure is that France’s debt profile makes it stand out, said Erik Norland, a senior economist of CME Group.

“France used a zero-rate period to massively leverage up its total debt, so it’s very, very vulnerable,” he said. “It’s strange to me that people would be more concerned about Portugal and Spain than France.”

(Updates with manufacturing PMIs in ninth paragraph)