Georgia’s acting central bank governor said the country is poised soon to revive a $289 million program with the International Monetary Fund, halted earlier this year amid questions over threats to the regulator’s independence and local enforcement of sanctions.

“Our common understanding and strong will is to put the program back on track as soon as possible,” Natia Turnava said in her first interview with an international news organization. While the timeline for restoring its “normal course” isn’t yet clear, Turnava said she’s hopeful it may happen in the “nearest months.”

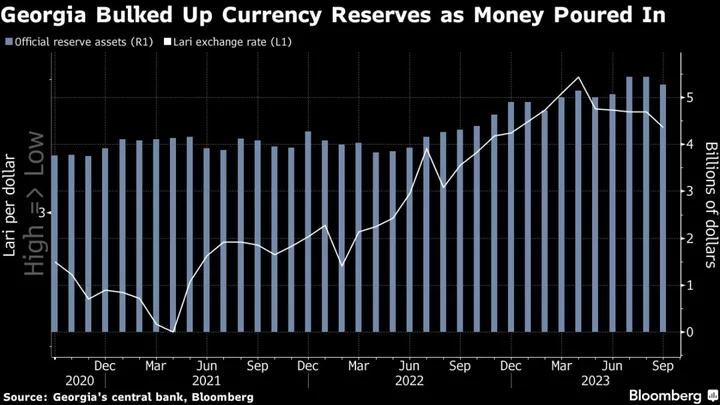

Unblocking the deal would provide reassurance for investors as the $30 billion South Caucasus economy moves past the regional fallout of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that reshaped trade and sent tens of thousands of people fleeing the war into Georgia. Money transfers linked to Russia have dropped sharply this year after Georgia received a windfall revenue estimated at about $2 billion in 2022.

Delays around the three-year IMF program — which Turnava said is now “suspended” — predate her appointment in June as the first woman to lead Georgia’s central bank. But the former minister of economy and sustainable development soon found herself at the center of a controversy engulfing an institution long viewed as among the most independent and respected in the nation of less than 4 million.

Drafted when Turnava’s predecessor neared the end of his term, a law this year potentially threatened the autonomy of the National Bank of Georgia by mandating several changes to its structure, including an increase in the number of executive members of the board. It also created the position of first vice governor — the job later given to Turnava — who’d assume the top role in the governor’s absence.

Soon after lawmakers introduced the bill in February, the IMF warned the measure risked “undermining the authorities’ hard-won credibility” and called for caution so that “central bank independence and credibility are safeguarded.”

Just over four months later, parliament approved the amendments by overriding the president’s veto, prompting the IMF to delay its second review of Georgia’s program. So far, it has only disbursed the first tranche worth $40 million.

After Turnava, 55, became first vice governor in June, she also took charge of the central bank in an acting capacity. Koba Gvenetadze’s seven-year term as governor ended in March, but the post remained unfilled because of disagreements between Georgia’s president and the ruling party.

The IMF program then went off the rails after Turnava moved in September to unfreeze local assets of Otar Partskhaladze, a former prosecutor general closely linked to Georgia’s political elite, after he was sanctioned by the US amid a wave of new Russia-related restrictions.

While Turnava defended the decision as necessary because a citizen couldn’t be subject to international sanctions without a Georgian court conviction, it prompted resignations by three central bank deputy heads. President Salome Zourabichvili also called on Turnava to step down and apologized for nominating her.

When asked about the status of Georgia’s program, an IMF spokeswoman, Khatuna Danelia, said it’s on pause even though the fund hasn’t made its suspension official. She confirmed that meetings have been held with the central bank in Tbilisi and referred Bloomberg to earlier comments by an IMF official in Georgia that expressed “concerns regarding the recent announcement by the NBG to alter its approach to sanctions.”

Overreaction, Misunderstanding

Turnava called the uproar an “overreaction” that resulted from “misunderstanding” the move.

But the backlash also cast a harsh light on the extent of political influence over regulatory practice in Georgia and the country’s relationship with Russia, with whom it fought a brief war in 2008. The government complies with — but hasn’t joined — the US-led campaign of sanctions against Russia and instead has allowed trade and commercial ties with Moscow to expand.

The US State Department said Partskhaladze acted to “influence Georgian society and politics for the benefit of Russia” after likely receiving help from Russia’s security service in obtaining a Russian passport.

Turnava said “fruitful discussions” with the fund’s officials at the IMF and World Bank’s annual meetings in Marrakech last month may have set the stage for breaking the impasse.

Moving Forward

As evidence of an effort to strengthen the institution’s autonomy, Turnava cited joint work with the IMF on drafting changes to the central bank law that would include measures such as adding independent non-executive members to the board — which she described as a “solution” that helps “bring more expertise.”

“We agree with them in building a stronger board structure by adding non-executive members,” she said. This week, the central bank named three international experts and economists as advisers to Turnava.

When it comes to Georgia’s stance on sanctions, Turnava said the IMF’s worry focused on the impact of her decision on the financial sector. The central bank is now reviewing existing legislation with the IMF and local lenders.

“Our decision didn’t affect the ability and capacity of the financial sector to enforce the sanctions,” Turnava said. “Georgia will never become a place for evading sanctions.”

As she navigates these challenges, Turnava is also steering Georgia’s first cycle of monetary easing since the Covid-19 pandemic. The key interest rate has already been cut from a multi-year peak of 11% to 10%, as inflation has slowed sharply.

Policymakers took a pause at their last meeting in October, pointing to risks that now include the Israel-Hamas war. Turnava said the benchmark may be lowered to around 9.5% this year, with inflation on track to come back to the 3% target only by the end of 2024.

“The low inflation allows us to exit tight stance of monetary policy very, very gradually,” she said.

--With assistance from Paul Abelsky.