Manufacturers from chemicals to metals and machinery curbed production last year in the fallout from Germany’s energy crisis. As the cutbacks linger, it’s a sign that a deeper industrial malaise is setting in.

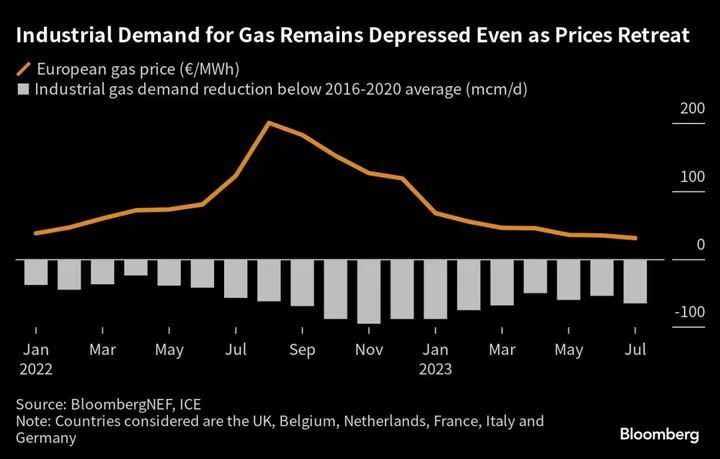

The record-high prices that were triggered by Russia’s squeeze on deliveries last year are now gone, but worsening economic conditions are hitting demand just as hard. Gas usage across Europe’s industrial landscape is projected to remain about 20% below 2021 levels, according to data from S&P Global Commodity Insights.

“It’s not just about prices anymore, but about the economic conditions,” said Erisa Pasko, a natural gas analyst at Energy Aspects. “We are still seeing a lot of weakness and a lot of uncertainty.”

The downturn is evident at the Gendorf chemical park located an hour east of Munich.

Some 4,000 people work at the site for chemical makers such as 3M Co., Clariant AG and Westlake Vinnolit GmbH. The park relies mostly on gas to meet its annual electricity demand of over 1 terawatt-hour — equivalent to supplying about 300,000 households, but this year less will be needed.

“There is currently no indication that the situation is improving,” said Tilo Rosenberger-Süß, spokesman for the hub’s operator InfraServ Gendorf, adding that the trend could lead to long-term demand destruction at the facility.

Read More: EU Cuts Euro-Zone Outlook as German Economic Woes Deepen

Despite an 80% decline from last year’s gas prices — which made some production unprofitable — Germany’s energy-intensive industry is struggling even more than the broader manufacturing sector. That’s especially true for chemicals.

VCI, the country’s trade group for the chemicals industry, expects production, not including pharmaceuticals, to fall by 11% in 2023. Meanwhile, the European Chemical Industry Council anticipates a drop this year of 8% across the region, with no imminent recovery in demand expected.

Germany plays a critical role in the industry’s weakness. Europe’s powerhouse economy started the third quarter with the biggest monthly decline in factory orders since the pandemic in 2020. The downturn in the country’s manufacturing core is probably severe enough to lead to a quarterly contraction, just after barely exiting a recession, according to a monthly survey of economists by Bloomberg.

After massive investment in liquefied natural gas infrastructure and soaking up cargoes on the global market, the risks of shortages this winter is limited. But that shock was been replaced by concerns about a deep-rooted recession, which has made German businesses hesitant to ramp up production again.

Read More: Germany Faces Grim Outlook as Business Confidence Worsens

With European economies strained by higher interest rates, there are fears that some gas demand might never come back. Some of it might be due to companies switching to renewable power, but others are also pulling up and moving elsewhere.

Hellma Materials, a Jena-based manufacturer of crystalline and optical components, has invested €20 million ($21 million) in a facility in Trollhattan, Sweden. The new site fulfills Hellma’s complex requirements with regard to electricity supply and industrial cooling water, Chief Executive Officer Thomas Töpfer said in a statement.

It’s not all grim. There are signs of recovery in refining, and some segments are too critical to cut for long.

Yara International ASA, Europe’s largest fertilizer maker, is still expecting higher demand for ammonia for the rest of the year. The company said it had only 10% of its European capacity curtailed, compared with 30% at the beginning of the year.

“Volatility in prices distorts the market and distorts buying,” Magnus Ankarstrand, Yara’s executive vice president for corporate development, said in an interview. “But eventually farmers and distributors have to buy because the market will need the fertilizer to produce the food that the world needs.”