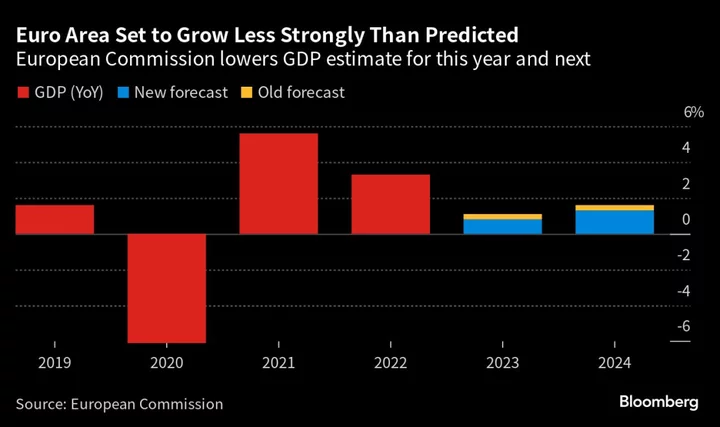

The European Commission cut its outlook for the euro-area economy, predicting it will be dragged down this year by a contraction in Germany.

Output in the 20-nation currency bloc will rise by 0.8% in 2023, compared with an earlier forecast for 1.1% growth, according to updated projections published Monday by the European Union’s executive arm. Next year’s outlook was lowered by the same amount, to 1.3%.

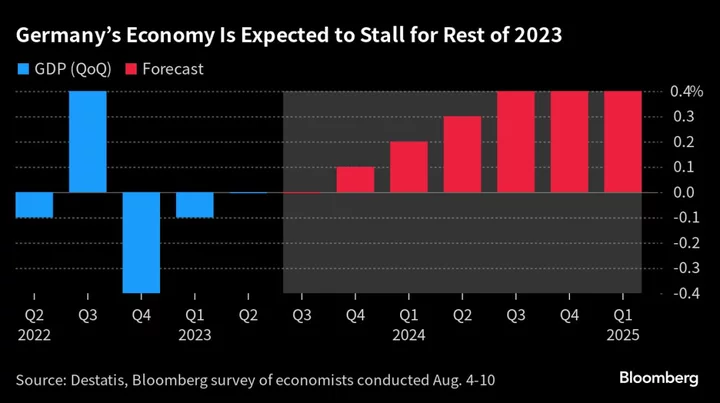

The region’s biggest economy is largely to blame. Germany, which had been expected to grow in 2023, is now facing a decline of 0.4%. The Netherlands saw an even heftier downward revision, to 0.5% from 1.8%. Spain and France, at the other end of the spectrum, are set to aid expansion.

Inflation will stay elevated and won’t retreat to the European Central Bank’s 2% goal. It’s seen at 5.6% this year, a little lower than previously envisaged, but a touch higher in 2024, at 2.9%.

The fresh numbers may stoke fears that the euro zone is becoming mired in a prolonged period of subdued growth and above-target inflation.

They may also offer a likely flavor of the ECB’s own quarterly outlook, which is due Thursday and will help officials determine whether to extend or pause their historic bout of interest-rate hikes.

“Weakness in domestic demand, in particular consumption, shows that high, and still increasing consumer prices for most goods and services, are taking a heavy toll,” the commission said. “The weaker growth momentum in the EU is expected to extend to 2024, and the impact of tight monetary policy is set to continue restraining economic activity.”

Despite dodging a recession in the wake of Russia’s attack on Ukraine, the euro region is struggling under the weight of higher energy prices, a surge in borrowing costs and waning demand in export markets like China.

Data released last week revealed output in the bloc barely grew in the three months through June, revised lower due to poor foreign sales. Surveys of purchasing managers point to a tough third quarter as Europe’s services sector follows manufacturing into a contraction.

Nowhere are such problems on starker display than in Germany, which has been weighed down primarily by a manufacturing slump. After enduring a winter downturn, its economy failed to expand in the second quarter and could shrink by 0.3% in the third, according to a forecast last week from the Kiel Institute.

“Of course the German economy has an impact for other countries,” EU Economy Commissioner Paolo Gentiloni told a news conference. “Overall, if the largest economy of the union is in negative — slightly negative — growth, this is affecting everyone.”

The souring backdrop has been on the minds of several ECB officials who say it’s time to halt the forceful tightening campaign they embarked on just over a year ago. Others, though, have signaled they’d be comfortable with a mild recession if that’s needed to get inflation back to 2%.

Investors are “maybe” underestimating the likelihood of a 10th straight rate hike, Governing Council member Klaas Knot told Bloomberg last week.

“Monetary tightening may weigh on economic activity more heavily than expected,” the commission said. But it “could also lead to a faster decline in inflation that would accelerate the restoration of real incomes.”

A Bloomberg survey of analysts published earlier Monday revealed a more pessimistic view to the commission’s. The euro-zone economy is seen growing by 0.6% in 2023 and 0.8% next year.

--With assistance from Harumi Ichikura and Alexander Weber.

(Updates with commissioner’s comment in 11th paragraph.)