European Central Bank officials keep insisting that interest rates need to stay high, but another stark slowdown in inflation suggests the economic picture is changing faster than they expected.

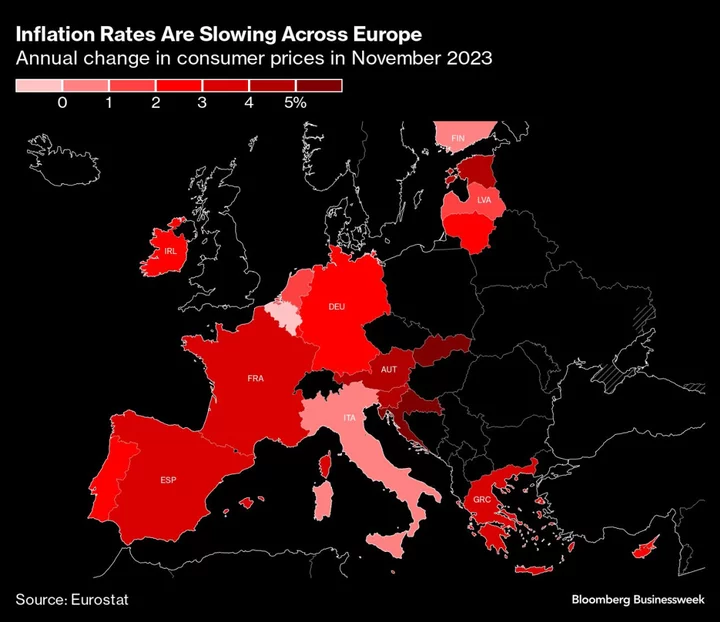

In three consecutive months, consumer-price growth has weakened more than economists predicted, and the outcome of 2.4% for November published on Thursday was closer to the ECB’s target than at any point since mid-2021. As recently as August, inflation was more than twice as fast.

Investors who were already betting on a reduction in borrowing costs as soon as April are now even surer, despite hawkish policymakers claiming no such move is in the offing. Traders shrugged last week when one official, Pierre Wunsch, even threatened that a hike could be needed to convince them.

Inflation is getting tantalizingly close to the 2% goal of the Frankfurt-based ECB, and recent outcomes now make it increasingly likely that its staff will have to lower a forecast that previously envisaged price growth at the target only in the second half of 2025.

Those projections will be released in just two weeks, when the ECB is widely expected to leave borrowing costs on hold for a second meeting and where President Christine Lagarde will face mounting scrutiny over her insistence on holding rates high as the economy languishes.

“When the ECB realizes at the beginning of next year that inflation is going down significantly faster than expected, talk about rate cuts is going to intensify,” said Joerg Angele, an economist at Bantleon in Zurich who was one of those closest to predicting November’s inflation retreat. “That would be reasonable, because if economic activity remains weak, I don’t see any reason not to lower interest rates to a neutral level.”

He sees the recent inflation outcome emboldening dovish policymakers who spent the past 18 months on the back foot as hawkish ECB colleagues set the tone to drive an aggressive series of 10 back-to-back rate hikes.

One of them, newly appointed Bank of Italy Governor Fabio Panetta, was quick to start the ball rolling. With inflation in his own country now a paltry 0.7%, he warned colleagues that rate hikes are proving more effective than anticipated.

“Disinflation is well under way,” he said on Thursday. “We need to avoid unnecessary damage to economic activity and risks to financial stability, which would ultimately jeopardize price stability.”

While the ECB’s price outlook is looking increasingly pessimistic, the Dec. 14 gathering may come too soon for a significant change in tone, not least for a central bank whose footwork has often been ponderous. By the time officials began raising rates in July 2022, most global counterparts had begun already.

But ECB officials also have reason for caution. They anticipate inflation should pick up again in December because of statistical effects making the comparison to last year less favorable.

The removal of some of the aid measures governments introduced to soften the energy-price spike after the Ukraine war will also stand in the way of a further rapid decline. In Germany, for example, temporary tax breaks for restaurant meals are ending in January.

“We know that November is the trough,” Janet Henry, chief global economist at HSBC Holdings Plc, told Bloomberg Television. “Headline inflation is probably — just given the base effects — going to start rising again.”

Core inflation, which strips out volatile elements such as energy and is the key measure policymakers have focused on, is also still higher than the headline measure, at 3.6%.

Such factors may give hawkish officials sufficient cover to stick to the message that borrowing costs need to restrict the economy for longer to stamp out inflation. Even after Thursday’s data, Bundesbank President Joachim Nagel — a leading hawk — stuck to his guns.

“The inflation risks are skewed to the upside — not least due to the current geopolitical situation,” he said. “That’s why I don’t rule out a further increase in interest rates. At the same time, it seems to me to be far too early to even think about a possible interest-rate cut.”

“A cut in the first meeting of next year is hard to see because headline inflation is going to go up, and the optics matter,” said Kamil Kovar, an economist at Moody’s Analytics. “But in March, it’s feasible to have a cut. It’ll require further weak reports, but it’s feasible.”

Investors now see an almost 50% chance that this scenario will play out, with a cut in April fully priced in. Just over a month ago, the expectation was for a first reduction in June.

Helping such speculation is an economy that also seems to be performing worse than expected. French output contracted in the third quarter, according to revised data on Thursday, and private-sector activity in the euro area has continued to shrink this month.

Some caution that despite Thursday’s figure, risks to the inflation outlook can’t be dismissed. A key question is whether companies will be able to pass on rising wages to consumers, and how wages will respond.

“Remember: inflation has been above target for over 2 1/2 years — they know which way the risks are still skewed,” HSBC’s Henry said, referring to the ECB. “For now, inflation is still too high, even if moving in the right direction.”

A forecast confirming inflation dropping back to target next year may change that, especially given the euro-zone’s history of too-low price growth before the pandemic, according to Kovar at Moody’s.

“If you have that in the forecast, it’s kind of hard to say we will just stick to a 4% deposit rate because we like it here,” he said. “At some level, the memory of the last decade will also start to play a role.”

--With assistance from Kamil Kowalcze.

(Updates with Nagel in 15th paragraph)