Far-right lawmaker Geert Wilders won the Dutch elections and said he plans to lead the country’s next government, in a shock result that will resound across Europe.

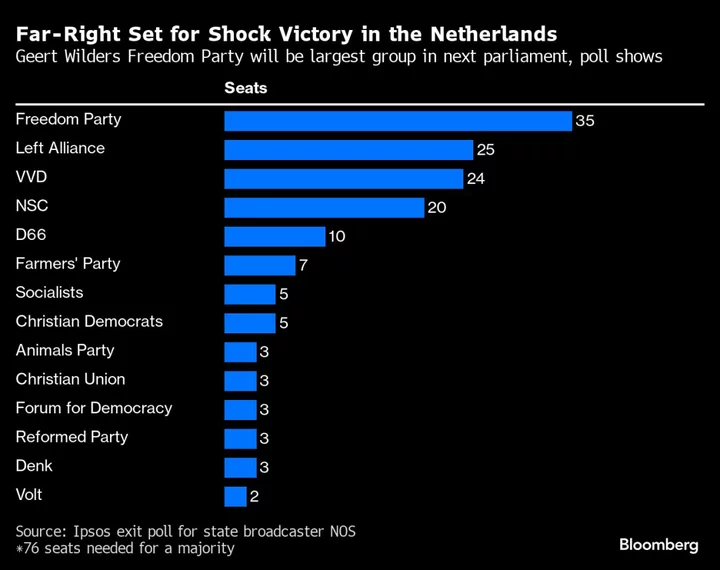

The frontrunner Dilan Yesilgoz-Zegerius conceded defeat after a late surge in the final days of the campaign catapulted Wilders’s anti-EU party past his mainstream rivals. Wilders’s Freedom Party will win 35 seats, according to an initial tally, more than doubling his representation from the previous parliament and giving him 10 more than his closest rival.

Only once in recent Dutch history has the leader of the biggest party not become prime minister.

Wilders’s victory presents a challenge to the European Union project in one of the bloc’s six founding members as the world braces for the potential return of Donald Trump after next year’s US election. Wilders has promised voters a binding referendum on leaving the EU and railed against a range of the bloc’s policies on issues like climate change and immigration.

“The hope of the Dutch people is that they will get their country back,” Wilders said after an exit poll published by state broadcaster NOS.

His prospects of leading the next government will hinge on his ability to forge alliances with rivals more to the center. In his post-election speech, Wilders called for a coalition that would include the liberal VVD, until recently helmed by outgoing prime minister Mark Rutte, which has indicated that it might be prepared to govern alongside him. “I am willing to compromise in talks with other parties,” he said.

A surge in the number of refugees since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as well as the spiraling cost of food and energy, has fueled support for far-right groups across the European continent. Germany’s Alternative for Deutschland now has more support than any of the parties in Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s coalition, while Giorgia Meloni came from nowhere to take power last year in Italy.

The Dutch election campaign highlighted how immigration has polarized voter opinion and driven support toward Wilders, for whom the topic has been a core issue for decades. The 60-year-old is known for his anti-Islamic views and has lived under police protection since 2004 on account of death threats.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, who has consistently been at odds with Brussels himself, was quick to congratulate him on his victory.

Wilders and his team hugged and cheered as the result was announced and sang along to the Rocky theme tune Eye of the Tiger. Reporters who watched his campaign team celebrate at a crowded bar in Scheveningen near The Hague did so from behind security glass.

“It’s customary that the biggest and winning party takes the lead in the formation process” said Stefan Couperus, an associate professor of political science at Groningen University. “He could become the leader of the new government.”

Wilders benefited from a strong showing in the campaign’s final election debates — and from the refusal of Rutte’s successor as party leader, Yesilgoz-Zegerius, to rule out working with him. The VVD leader signaled before the election that she might go into coalition with Wilders although, after the exit polls dropped, she cast doubt on whether her rival would be able to secure the votes he needs to govern.

“I don’t see that happening because Mr. Wilders can’t form a majority,” she said. “However, the ball is now in Geert Wilders’ court.”

One cautionary precedent for Wilders came in Spain this month, where Socialist Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez clinched a surprise third term despite suffering defeat to his center-right rival in July’s election. Sanchez stitched together support from seven different parties to turn the electoral math in his favor after the two right-wing parties fell short of a majority.

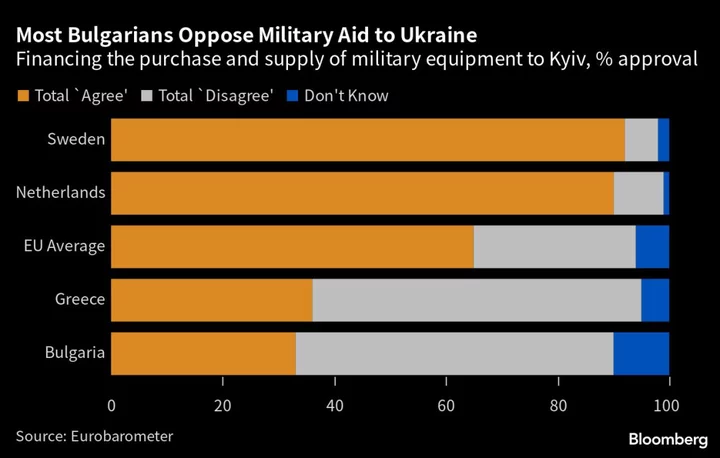

If Wilders does end up leading the next Dutch government, it would elevate a euroskeptic into the heart of one of the union’s stalwart members. He has called for the Netherlands to withdraw from its international climate obligations, and demanded a halt to aid to Ukraine.

Under Rutte, the Netherlands pledged to send F-16 fighter jets to Ukraine next year and has been leading the European effort to train Ukrainian pilots.

Despite campaign pledges on banning the Koran and shutting down mosques, “Geert Wilders conveyed a more moderate message than in previous years,” said Couperus. “That seems to have worked electorally.”

Wilders has been a member of parliament for 25 years but only once taken part in government, between 2010 and 2012 when he had an arrangement to support Rutte’s first, minority coalition from outside. Rutte later ruled out working with him, after Wilders made comments insulting people of Moroccan descent for which he was censured by the courts.

It’s likely that the outgoing caretaker government led by Rutte could preside for a while, especially if Wilders struggles to make headway in the coalition-building process. At the last election, four parties were needed to broker a majority government and the negotiations took a record nine months.

“The PVV cannot be ignored, and wants to work together with other parties, and that means that we and they have to step over their shadow,” Wilders said.