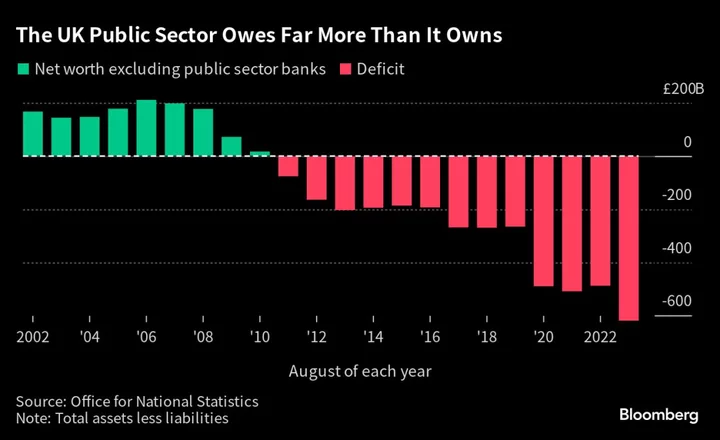

Governments should not use net worth as a fiscal target because it “tell us little or nothing about government’s ability to access capital markets or service its debt,” according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

The measure of what the British state owns and what it owes has won support over the last few years because it does not penalize governments for borrowing to invest. Under a net worth rule, the value of a hospital counterbalances the debt taken to build it.

The Conservative government and the opposition Labour Party have almost identical fiscal rules, with the binding goal to have debt falling as a share of GDP. Labour has promised to “take greater account of public sector assets as well as debt in fiscal policy,” which the IFS said “could imply some sort of target for public sector net worth.”

Rachel Reeves, Labour’s shadow chancellor, has faced calls to make net worth a key principle. Both Jim O’Neill, a former Conservative minister who advised Reeves, and Andy Haldane, the former Bank of England chief economist, are keen supporters of the rule.

However, in a pre-released chapter of its Green Budget, the IFS attempts to demolish efforts to promote net worth. While there is a “strong case” alongside more traditional rules, “it ought not to be at the center of the UK fiscal framework,” the think tank said. Labour’s current proposal is “sensible, but we caution against going further.”

The idea of a balance sheet target was originally backed by Richard Hughes, who is now chair of the Office for Budget Responsibility that checks the government fiscal performance. Since then, the Office for National Statistics has developed a monthly measure of net worth, which generated greater interest.

Net worth’s attraction is that a narrow focus on debt “can be misleading or unhelpful,” the IFS said, particularly in the case of privatizations or nationalizations. Privatizations appear to reduce the debt, flattering the public finances because no asset loss is disclosed. For the same reason, nationalizations appear to be enormously costly.

The IFS said the problem with net worth is that the government cannot sell assets like roads or hospital buildings to meet financing needs. Nor can an increase in estimated asset values “be taken as a signal that the government can afford to borrow more.”

Ben Zaranko, senior research economist at IFS, said: “The current fiscal rules are crude and can be, and have been, gamed. Keeping a watchful eye on a measure of public sector net worth would be sensible and could discourage some forms of bad fiscal behavior. But that doesn’t mean that it can form the basis of a good fiscal rule, and it doesn’t mean that changes in net worth are a good guide for policy.”