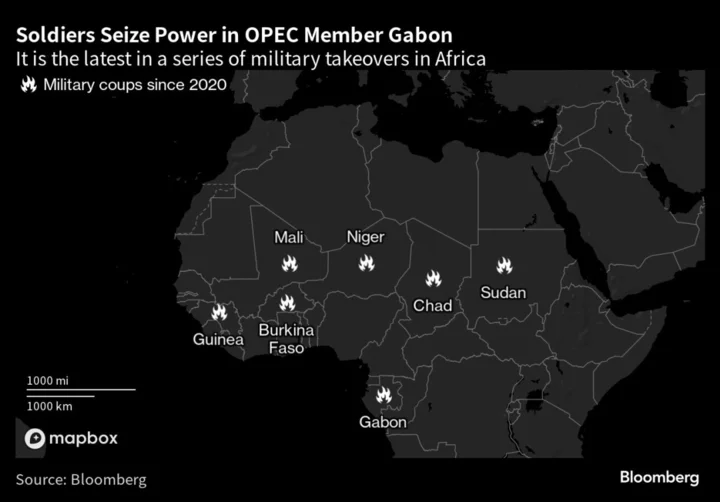

The coup in Gabon that ousted a key French ally in Africa shook up bond investors by destabilizing one of the region’s few international borrowers.

August’s unseating of long-term President Ali Bongo led to record declines in Gabon’s dollar debt, and quickly focused the market’s attention on who may be next. Losses cascaded to neighboring countries, such as Cameroon and the Republic of Congo, where aging rulers preside over oil-exporting economies bound by a currency union.

In fact, the selloff proved to be a blip, with premiums for debt issued by Gabon, Ivory Coast and Senegal falling within weeks to levels seen before the military takeover.

Still, the Gabon coup opened a new faultline in a bond market that could once look past upheaval in Sahelian countries like Niger, Chad and Mali — a group of lower-income nations with no outstanding eurobonds.

“That’s why the Gabon coup was so unexpected, and that’s why the market is a bit nervous about having coups in other African countries which have had very long-standing rulers with regimes that have so far appeared to be stable,” said Carlos De Sousa, an emerging-markets money manager at Vontobel Asset Management AG in Zurich.

The verdict of investors matters because global markets can be a lifeline for cash-strapped governments whose finances are deeply in the red. But the appetite for high-risk assets is now on the wane, threatening to add even more pressure to a political environment in parts of Africa that’s already grown volatile.

Threats to stability on the continent remain high on investor radars, with Burkina Faso’s military junta saying it thwarted an attempted coup this week and rumors — since denied — of a government overthrow in the Republic of Congo.

“Governance forms the bedrock of credit quality,” said Adriaan Du Toit, the London-based director of emerging-market economic research at AllianceBernstein. “Political disruption shakes this foundation and shrinks the investor base.”

Bondholders averted the worst as higher oil prices became a firewall to contagion. The threat of regional sanctions against Gabon has also receded, with its new leadership vowing to honor the nation’s debt commitments and boost investment into an economy that has higher GDP per capita than South Africa.

Gabon’s dollar debt plunged after soldiers seized control of the country, sending the yield on notes due in 2025 to as high as 20%. It’s since come down to 14%, approaching this year’s average of around 11%.

As nerves eased over the regional fallout, the recent performance of the Republic of Congo’s lone international bonds now differs little from broader declines in an index of emerging dollar debt, which are all down about 3% since Aug. 30. Cameroon’s 2025 dollar securities are little changed in illiquid trading during the same period.

“African bonds have performed well on average over the last month, but bonds from countries like Cameroon and the Republic of Congo have suffered lately, as some investors draw similarities with Gabon,” said De Sousa, whose portfolio at Vontobel includes debt issued by Gabon and Cameroon.

There have been nine coups across Africa in the past three years, largely driven by growing insecurity in the Sahel. But the problems in Central Africa are different — Gabon’s oil-rich neighbors Cameroon, Republic of Congo and Equatorial Guinea are run by aging dictators who’ve enriched themselves, left their people impoverished and failed to diversify their economies.

Deteriorating public finances, alongside other challenges that include dwindling reserves, will add to the fear of military takeovers stalking the markets, according to Thalia Petousis, portfolio manager for Cape Town-based money manager Allan Gray who helps oversee its Africa bond fund.

“Borrowing rates that they can achieve via the Eurobond markets have been prohibitively high,” Petousis said. Central African countries have “struggled with large debt loads and both fiscal and current-account deficits for some time.”

Gabon gave investors a lesson in political risk — and also an opportunity.

As the market explored the vulnerabilities across the region, it’s the strength of Gabon’s neighbors that stood out for Jupiter Asset Management Ltd. Cameroon’s Paul Biya, 90, and Republic of Congo’s Denis Sassou Nguesso, 79, have both ruled their countries for over four decades — long-running dynasties like Gabon’s that most geopolitical analysts view as being at the highest risk of being overthrown.

A rally in oil prices has left Cameroon’s debt with “a really attractive price and yield right now,” said Vikram Aggarwal, fixed-income fund manager at Jupiter, which already has exposure to the West African nation’s securities. “And investors get more than compensated for the risks,” he said.

While steering clear of Gabon’s debt before and after the coup — especially as questions linger about its program with the International Monetary Fund — Aggarwal said “some of the neighboring countries are slightly more interesting.”

“The fact that oil prices are where they are is definitely beneficial to Gabon, Congo and other countries close by,” he said. “It brings dollars into the country and makes it easier to remain current on their debt. And, if they are in a difficult position politically — from an economic standpoint, at least, that gives them greater firepower.”

--With assistance from Selcuk Gokoluk, Timothy Rangongo and Netty Ismail.