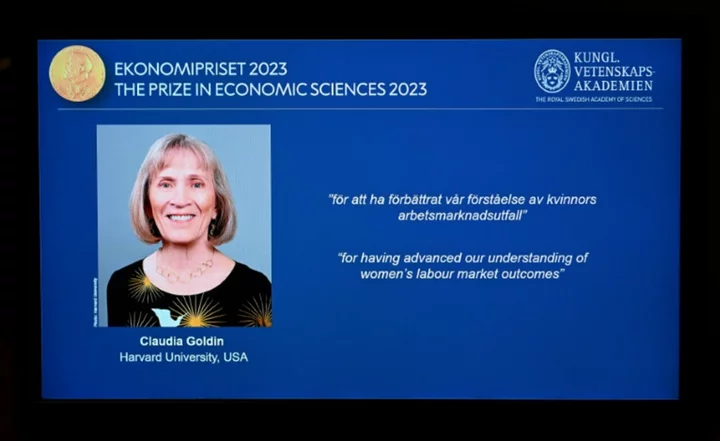

Claudia Goldin has long thought of herself as a kind of detective within economics, employing tools across academic disciplines in a quest to examine how women fit into the workforce.

On Monday, Goldin, the first woman to be tenured at Harvard University's economics department, attained the "dismal science" most exalted honour: the Nobel Prize for Economics.

Reached by telephone, Goldin told AFP the Nobel is a "very important prize, not just for me, but for the many people who work in this field and who are trying to understand why there is so much change, but there are still large differences" in pay.

In her sleuthing, Goldin, 77, has sought to reveal the reasons for the long-standing gender pay gap, including the challenges women have encountered in balancing family and professional responsibilities since the early twentieth century.

Goldin has focused on five periods: the 1900-1920 period when the few women who garnered college degrees had to choose between work and family, followed by the 1920-1940 phase when women left the workforce and started families during the Great Depression.

In the years after World War II through to about 1960, women were discouraged from entering the workforce instead of raising families. But their daughters, raised in the 1970s and 1980s, benefited from the birth control pill, with more women choosing careers and more than a quarter not having children.

The most recent generation of women is still navigating these dynamics, benefiting from evolving technology that has permitted greater flexibility on when to have children, but still confronting a grinding pay gap.

In her 2021 book, "Career and family: women's century-long journey towards equity," Goldin explored the effect of what she termed "greedy work" -- jobs with inflexible or unpredictable schedules that pay better.

Through her research, Goldin determined that women were more likely to abandon such jobs, while men are more likely to be enticed by the higher pay.

"Under these conditions, women will shift to a firm with less demanding hours or leave the workforce," Goldin said in a 2021 interview with Harvard Business Review.

- 'Neglected' subject -

Goldin described her unorthodox approach in an autobiographical essay for a 1998 book on economists at work.

"There has often been no agenda or program, no particular theory that must be followed," she wrote. "Yet the subconscious produces nagging questions."

In the years after graduate school, Goldin focused initially on the economic history of the South after the Civil War.

But around 1980, Goldin began to "realise that something was missing" from the study of economics: the wife and mother.

"I neglected her because the sources had.

"Women were in the data when young and single and often when widowed," she wrote. "But their stories were faintly heard after they married, for they were often not producing goods and services in sectors that were, or would be, part of (gross national product)."

Goldin's pioneering approach included launching in 2014 undergraduate women in economics program, an initiative to encourage more female economics major.

Born in the Bronx, New York in 1946, Golden was initially fascinated by archeology and the mummies at the New York's Museum of Natural History.

When she entered Cornell University, Goldin planned to study microbiology, but soon shifted ground after taking a course on industrial organisation with economist Alfred Kahn.

Goldin is married to fellow Harvard economist Larry Katz, with the two sharing a passion for bird watching and Pika, a 13-year-old Golden Retriever whose exploits are chronicled on her web page at Harvard.

Goldin told AFP she still thinks of herself as a detective, someone who when faced with a problem, knows "I just have to find the facts, figure it out and I'll solve the problem."

ber-jmb/cw