China’s deepening property rout is pushing the nation’s central bank toward a style of policy it has long criticized: Quantitative easing.

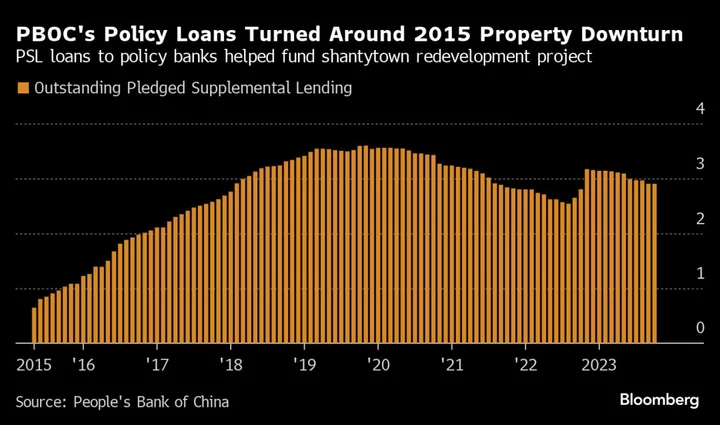

Bloomberg News has reported that the People’s Bank of China may provide at least 1 trillion yuan ($140 billion) in low-cost funding to construction projects via so-called Pledged Supplemental Lending. Under that program, the central bank has provided cheap long-term cash to policy banks (by accepting their loans as collateral) to fund lending to the housing and infrastructure sectors.

Unlike QE programs undertaken by the Federal Reserve and others that involve large-scale bond buying to push down yields, China’s version is more targeted. The PSL was used between 2014 and 2019 to help fund a home building spree, leading some economists to describe it as Chinese-style QE because of the resulting creation of money and expansion of the central bank’s balance sheet.

“After so much policy relaxation, stimulus and relief, the property sector still hasn’t shown any obvious improvement. All traditional tools have been used, so what’s left are only unconventional tools,” said Lu Ting, chief China economist at Nomura Holdings Inc. “The possibility of using central bank funds to rescue unfinished housing projects is increasing.”

The property sector — which at its peak made up about a quarter of China’s economy — is still plunging, with home prices falling the most in eight years in October. Policy measures so far including mortgage rate cuts, relaxed purchase requirements and financing aid to developers have failed to turn around the crisis.

Developers — facing increasing liquidity pressure as funding from loans and sales dry up — need 18.9 trillion yuan in 2023 to repay short-term liabilities and finish pre-sold homes, Bloomberg Economics estimates. The funding gap, which is equivalent of 15% of GDP, will be of a similar size in 2024.

QE Skeptics

The PBOC has long opposed the QE policies of global counterparts and pledged to keep “normal” monetary policy for as long as possible. The central bank did not respond to a faxed request for comment.

Former Governor Yi Gang, whose tenure ended in July, said central banks should try their best to avoid asset purchases because in the long run they’ll “damage market functions, monetize fiscal deficits, harm central banks’ reputation, blur the boundary of monetary policy and create moral hazard.” His predecessor, Zhou Xiaochuan, warned in 2010 that QE in the US could spur negative effects for the world.

In a policy report Monday, the PBOC contrasted its position to not buy government bonds with that of the Fed and the Bank of Japan.

China’s commercial banks hold some 64% of sovereign bonds under funding support from the central bank, the report said — far higher than the share held in the US and Japan, which is below 7%. The PBOC said it would push for more companies and residents to buy sovereign bonds to diversify the portfolio of the holders, and insure the smooth issuance of those bonds.

Broad monetary easing hasn’t been effective in reviving borrowing demand because of weak business and consumer confidence. The country’s Communist Party-controlled parliament warned of “funds idling between banks, or between banks and large enterprises” in a meeting last month.

The PBOC has twice cut policy interest rates and the reserve requirement ratio in 2023, yet property-related borrowing is still shrinking. Room for more conventional policy support is narrowing.

The average RRR, which determines the amount of cash banks must keep in central bank reserve, has declined to 7.4%, inching close to the implied 5% minimum considered necessary for maintaining the health of the banking sector. The key one-year policy rate is just 2.5% and additional easing would further widen the gap with US rates, putting the yuan under additional depreciation pressure.

PBOC Governor Pan Gongsheng — who took office this summer — has also vowed to provide emergency liquidity support to heavily indebted local governments in order to prevent local debt risks. Market participants believe that this may become yet another tool added to the central bank’s list of structural monetary policies, adding to expectations for more targeted easing.

PSL Success

The PBOC’s previous use of PSL for the rebuilding of shantytowns was instrumental in halting the previous property downturn.

The central bank provided 3.6 trillion yuan in PSL loans to policy banks over the span of five years. The policy banks — which are driven by government goals more than profits — used the money to help local governments and developers demolish old homes and provide cash compensation so homeowners could purchase new apartments.

That lifted demand in the small cities where the program took place and reduced inventory, eventually resulting in soaring housing prices. The shantytown program drove over 7 trillion yuan in total investment as it also received funding from other sources including bank loans and government spending, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co estimates.

Xing Zhaopeng, senior China strategist at Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd., says the PSL program “looks more like an off-budget fiscal activity” funded by the central bank, even though the PBOC calls it a structural tool. It’s “akin to debt monetarization” as the policy banks are a part of the government and their loans are taken by the PBOC as qualified collateral, Xing said in a recent report.

It’s unclear how big an impact PSL funds will have this time around as details haven’t been announced. Localities may prefer using housing vouchers instead of cash compensation for households, which means families can use government-issued vouchers to purchase unsold apartments from developers, rather than using cash.

ANZ’s Xing expects the PSL to be “less reflationary” this time around given the over-supply of housing and households’ weaker expectations for home prices.

Chinese TARP?

Macquarie Group Ltd. economists led by Larry Hu see the need for another Western-style policy tool: A fund that could be the lender or buyer of last resort. That would be similar to the Troubled Asset Relief Program that was introduced in the wake of the global financial crisis that allowed the US government to buy toxic assets to stabilize the financial system when Washington was cleaning up its own property crisis in 2008.

The PBOC has already expanded its balance sheet at a rapid pace in recent months to provide loans to banks. This has been to help lenders absorb a flood of government bonds sold to support fiscal funding and increase lending to targeted areas, such as the green sector. The central bank’s total assets climbed 8.6% to 43.3 trillion yuan in October from a year ago, expanding at the fastest pace since 2014.

“There are some similarities between the Chinese central bank’s practices to QE, in that its balance sheet has to expand,” said Le Xia, chief Asia economist at Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria SA. “It’s a choice that has to be made, and the most optimal one among all the bad choices.”