President Xi Jinping signaled that a sharp slowdown in growth and lingering deflationary risks won’t be tolerated, making a series of rare policy moves to boost sentiment in the world’s second largest-economy.

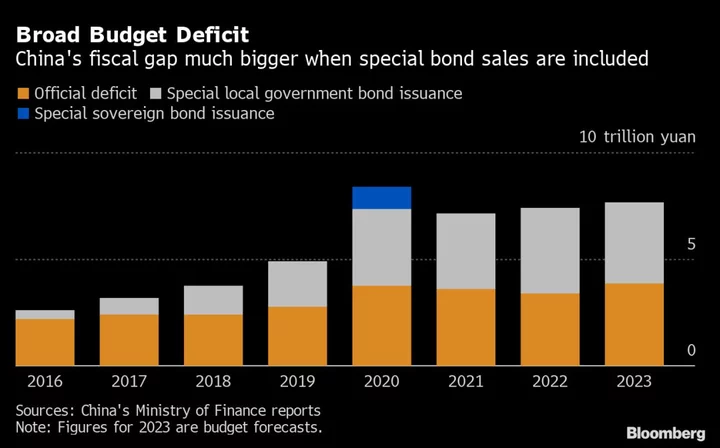

Within a 24-hour window on Tuesday, China increased its headline government deficit to the largest in three decades, unveiled a sovereign debt package that marked a shift from its traditional growth model, and Xi made an unprecedented trip to the central bank — sending a powerful message about his focus on the economy.

The one-trillion-yuan budget boost and willingness to exceed a long-adhered to 3% debt-to-GDP limit displayed a determination by Beijing to shore up growth for 2024 and avoid complacency. That comes even after strong economic data published this month put the government on target for its 5% goal this year. China will next week hold a twice-a-decade financial policy gathering that may provide more policy clarity.

“The landing of the surprising policy despite surprising third-quarter GDP data may be due to policymakers’ acknowledgment that the pressure to stabilize growth next year will increase,” Shenwan Hongyuan Group Co. analysts including Jia Dongxu wrote in note late Tuesday.

The stimulus raises expectations for the economy in 2024, and comes after several government-linked economists called for a growth target as high as 5% for next year.

China is grappling with a protracted property crisis, a worsening crunch in the $9 trillion local government debt market, and the threat of deflation. The nation’s economy wide measure of prices, the GDP deflator, was negative for two consecutive quarters for the first time since 2015.

Chinese equities reacted positively to the support measures, although traders doubt if the rally is sustainable. The CSI 300 Index gained 0.7% as of 2:10 p.m. local time, halving its earlier advance. The Hang Seng China Enterprises Index was up 1.5% after gaining more than 3%.

Today’s rally is offering investors hopes that the stock market’s rout may ease, which hit several grim milestones over the past week that included a wipe-out of all the reopening gains in the CSI 300 Index.

Local Governments

The move to use the central government’s balance sheet to issue 1 trillion yuan ($137 billion) in sovereign bonds for construction projects suggests a shift away from China’s previous stimulus model, which relied on local governments adding leverage.

Those local governments are finding it harder to service existing debt this year due to the property downturn. Beijing may be more willing to absorb more debt to buoy growth as local governments’ off-budget borrowings become more unsustainable, Nomura Holdings Inc. economists led by Lu Ting wrote in a note.

Half of the bond issuance will be spent early next year, while local government bond quotas can also be assigned early, China’s Communist-controlled parliament said when announcing the moves.

“The extra central government bonds and early local government bond issuance should ensure the rebound that started in August continues into the new year,” said Adam Wolfe, emerging markets economist at Absolute Strategy Research.

China has rarely adjusted the budget mid-year, having previously done so in periods including 2008, in the aftermath of the Sichuan earthquake and in the wake of the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s.

The headline deficit ratio of 3% outlined Tuesday would be the highest since the central-local tax sharing reform in 1994, according to the Shenwan analysts note.

The budget boost will lift GDP growth by 0.1 percentage points in the fourth quarter and 0.5 percentage points in 2024, according to Bloomberg Economics analysis. The move signals Beijing is “taking steps to help local governments, which are facing constraints in delivering stimulus,” economist David Qu wrote in a report.

No Bazooka

The support package remains conservative in several ways. First, the size of support, equivalent to about 0.8% of GDP, is small relative to “bazooka” stimulus worth multiple percentage points of GDP that China has used during past downturns.

The package “is not huge or big” and aims to support growth while “trying to make sure the debt is not increasing in a dramatic way,” Zhu Min, former deputy governor of the People’s Bank of China, told Bloomberg TV in an interview. China’s GDP could grow between 4.5% and 5% next year, he added.

Economists see the package as allowing local governments to keep infrastructure investment — which grew 6.2% on-year in the first nine months of this year — expanding at its current pace, rather than accelerating. That’s because local governments issued their entire quota of “special purpose” bonds used mainly for construction at the end of September, leaving a gap in their funds toward the end of this year.

Another traditional feature of the stimulus is its focus on construction. Economists have called for China to begin offering stimulus more directly to the household sector, arguing that payments to consumers could provide a greater boost to the economy than infrastructure investment.

While Xi’s shift away from saddling local governments with the responsibility for driving growth could bode well for China’s economy in the long-term, his reticence for bigger stimulus could protract that process.

“Besides demonstrating Beijing’s commitment to growth, the fact that deficit is entirely financed by central government is an encouraging move,” said Houze Song, a fellow at the Paulson Institute. “Nonetheless, Beijing still refuses to consider income transfer to households, which will delay the rebalancing of the Chinese economy.”

--With assistance from Fran Wang, Jacob Gu, Stephen Engle and Zhu Lin.