When the US first embraced “de-risking” to get Europe on board with measures to deny key technology to China, officials in Beijing dismissed the term as no different than decoupling. Now they are trying a new strategy: Redefine the concept.

Chinese Premier Li Qiang last week acknowledged the legitimacy of de-risking while speaking to CEOs on a trip to Germany, but said it should be decided by business leaders instead of governments. He also warned that risks shouldn’t be “exaggerated” — opening a discussion on what exactly poses a serious threat to national security.

Li hit the theme again on Tuesday at a high-profile economic forum in China known as “Summer Davos,” where he told delegates “if there is risk in a certain industry, it’s not the call or decision of a particular organization or a single government.”

“Governments and relevant organizations should not overreach themselves,” Li added. “Still less, overstretch the concept of risk or turn it into an ideological tool.”

At the same time, China is trying to improve its image among overseas investors after a high-profile crackdown on consultancy companies. On Tuesday, President Xi Jinping told visiting New Zealand leader Chris Hipkins in Beijing that China would better protect interests of foreign businesses.

The rhetorical shift is China’s latest effort to fight back against efforts by the US and Europe to prevent the world’s second-largest economy from obtaining advanced technology. The push to drive a wedge between companies and their governments could spark a debate in Western capitals that could ultimately water down any proposed measures that would hurt China’s economy.

“The key lies in what China believes are different assessments of risk by companies and by governments,” said Deborah Elms, founder and executive director of the Asian Trade Centre. “The former is probably assumed to be much less problematic, with firms taking a narrow view of risk.”

China’s direct appeal to business leaders comes as Europe and the US spearhead fresh tools to further curb Beijing’s access to advanced chips and other technologies. “Allowing companies to be in the driver’s seat would mean supply chains would operate without much government interference,” said Zhou Xiaoming, a researcher at the think tank Center for China and Globalization.

The European Union this month unveiled its economic security strategy, which outlines critical sectors that autocrats could weaponize. While that review was prompted by the bloc’s over-reliance on Russian energy, its China implications bring Europe closer to the US goal of removing Beijing from sensitive sectors.

US President Joe Biden is pushing forward with an executive order that could cut off certain US investments in China, according to people familiar with the matter. That would follow sweeping curbs imposed last October that limit the sale of chip-making equipment to Chinese customers.

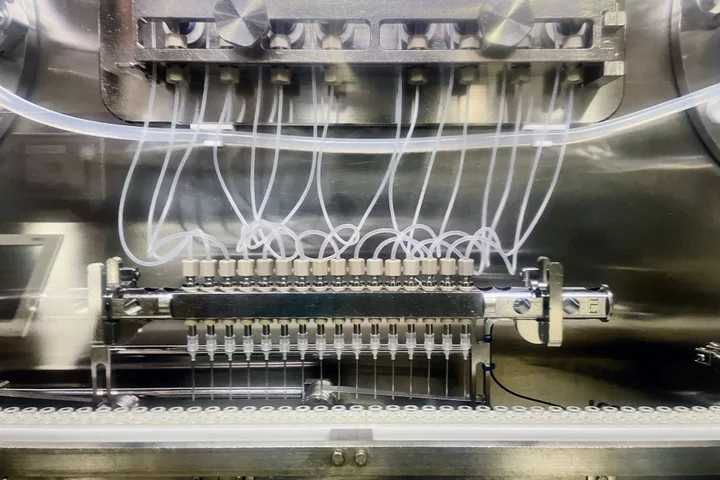

Those export controls saw the three biggest US manufacturers of advanced chip-making machines lose almost $5 billion in sales this year, according to estimates from the firms.

Despite the rhetoric, neither the US or Europe has articulated a clear definition of what constitutes a risk. Biden said at a Group of Seven leaders summit in Japan that US curbs should apply to a narrow set of technologies critical to “national security” — a broad term that casts a wide net in a world many everyday items have chips.

“Everyone is talking about de-risking but we think it’s a concept that is not very well-understood,” said Jens Eskelund, president of the European Chamber in Beijing. “There’s still a lot of work to be done by organizations such as ourselves and other stakeholders in trying to define what de-risking actually means.”

Divisions even within Europe on de-risking were evident at Summer Davos, where Peter Szijjarto, the foreign minister of Hungary — a nation with one of the EU’s most pro-Chinese governments — said decoupling from China would be a “brutal suicide.”

Business Allies

Beijing’s warmer ties with business leaders compared to some Western politicians was on display earlier this month when President Xi Jinping called American billionaire Bill Gates an “old friend” during a meeting in Beijing. Days later, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken was granted only a brief audience with the Chinese leader in the capital. Xi and Biden haven’t spoken since November.

Senior Communist Party officials also recently rolled out the red carpet in China for the chief executive officers of JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Tesla Inc., and a host of other foreign business chiefs.

While it remains to be seen how business leaders respond to Li’s call to challenge their governments’ economic interventions, he signed deals in Europe last week to deepen China cooperation with Airbus SE, BASF SE, BMW AG, Mercedes-Benz Group AG and Volkswagen AG. Li told those firms that risk prevention and cooperation are “not mutually exclusive.”

Michael Hart, president of the American Chamber of Commerce in China, said most companies prefer some moderate form of risk management. In the wake of Covid export disruptions, for example, many firms have added an offshore manufacturing base, a strategy known as “China plus one.”

Henry Gao, who researches Chinese trade policy at Singapore Management University, said the risk prevention measures Li supported companies pursing was fundamentally different to politicians’ de-risking strategies.

That could lead to both sides talking past each other, but perhaps that was the entire point.

Gao said: “It’s the same good old divide and conquer tactics.”

--With assistance from Lucille Liu, Yujing Liu and Debby Wu.

(Updates with Xi comments in fifth paragraph.)