A Canadian startup raised $55 million from venture capital firms and governments to begin a carbon-capture plant in Quebec, using early-stage technology that aims to suck millions of tons of emissions out of the atmosphere and oceans.

Deep Sky Corp. was founded by Frederic Lalonde, chief executive officer of Hopper Inc., a Montreal-based air-travel application company that’s one of Canada’s most valuable technology startups.

Whitecap Venture Partners, BrightSpark Ventures, the venture arm of Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System, and the Canadian and Quebec governments participated in the Deep Sky funding round for its first large-scale carbon removal plant.

“Even trees are not enough,” Lalonde said in an interview. Hopper has planted 25 million trees to try to offset the carbon footprint of its users and has a commitment for 30 million more, but he wants to go further. “What else could I buy that actually cancels out the emissions of the plane?”

That’s why he launched Deep Sky. Its initial objective is to remove as much as 300,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide a year from air and water, from a location to be determined in Quebec. The new capital will be used to select and test the best process, then plan and start the first phase of the plant.

“In searching for Canada’s next big bet and upon learning about Deep Sky, it became clear that this is a team and a technology worth supporting,” Whitecap’s Shayn Diamond said in a statement.

Read More: Big Promise, Little Success: The Precarious State of Carbon Capture

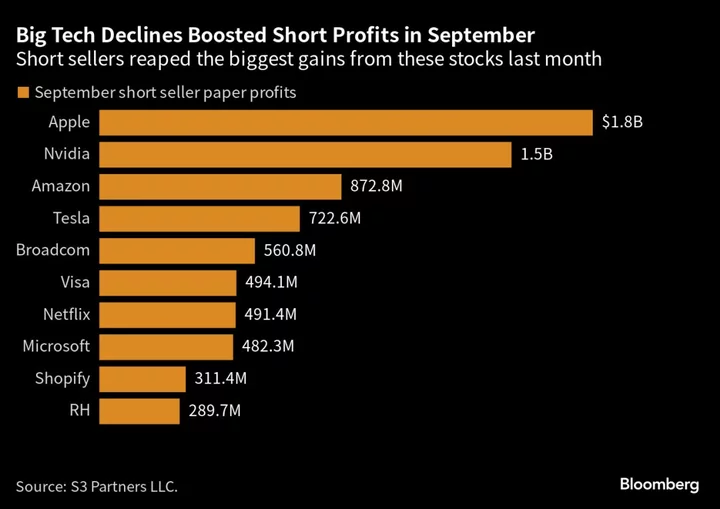

BloombergNEF reported in August that large corporations including Microsoft Corp. and Shopify Inc. are buyers of direct-air capture offsets, as they are “looking to diversify their sustainability portfolios and willing to pay the premium price tag.”

The report added that potential demand now outweighs supply 20-fold, as the technology is still in a “nascent” state. In fact, fewer than 30 direct-air capture plants have been commissioned so far in the world, according to the International Energy Agency, capturing only 10,000 tons of carbon dioxide per year. But there are plans for at least 130 facilities at various stages of development, the IEA said.

There’s a long way to go before Deep Sky can reach its goal. The firm has partnered with a dozen direct-air capture companies such as London-based Mission Zero Technologies Ltd. to test their technologies.

“We’re trying to figure out what will scale,” said Lalonde. “If you think of this century as our last chance to cool the earth, we’re going to need to be at around 20 billion tons a year of capacity removal by mid-century.”

As much as C$500 million ($365 million) will be required to bring the project to full scale. Another challenge is the 100 megawatts of electricity needed to run the facility. Hydro-Quebec, the provincial-owned utility, has become stricter on project approvals for its renewable hydroelectric power in the face of a looming shortage.

Lalonde argues that the project’s energy consumption can be timed so that it’s “throttling down” at times when other industries and consumers need more power.

“The allocation of megawatts intended to decarbonize the environment is essential,” Quebec Energy Minister Pierre Fitzgibbon said during a news conference.

(Updates with comments Quebec’s energy minister and additional information direct-air capture market.)