Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government won’t lower its immigration targets despite growing criticism that drastic population growth worsens existing housing shortages.

In one of his first interviews a week into his new cabinet role, Immigration Minister Marc Miller said the government will have to either keep — or raise — its annual targets for permanent residents of about half a million. That’s because of the diminishing number of working-age people relative to the number of retirees and the risk it poses to public service funding, he said.

“I don’t see a world in which we lower it, the need is too great,” said Miller, who’s expected to announce new targets on Nov. 1. “Whether we revise them upwards or not is something that I have to look at. But certainly I don’t think we’re in any position of wanting to lower them by any stretch of the imagination.”

Globally, advanced economies are confronting similar challenges from decreasing birth rates and aging workforces, and many are competing for skilled workers. But while immigration for some countries is a divisive issue that can polarize voters and even topple a government, Canada has comfortably relied on public support to open its doors more widely for working-age newcomers.

Miller’s comments suggest the government is still counting on that backing to grow its population rapidly to stave off long-term economic decline. Trudeau’s government has consistently raised its target for permanent residents. Last year, foreign students, temporary workers and refugees made up another group that’s even larger, bringing total arrivals to a record one million.

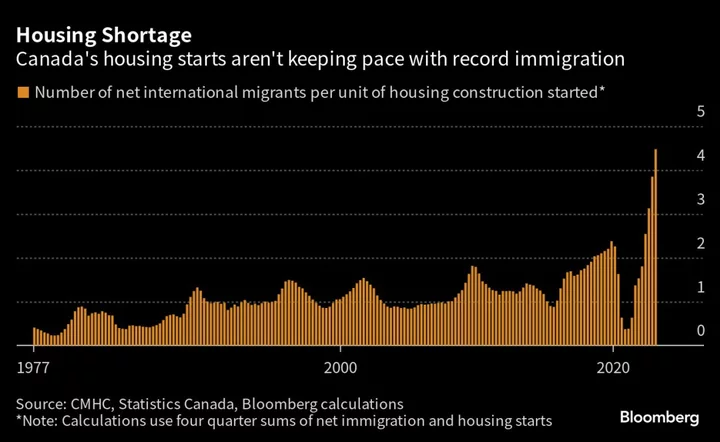

In the short term, however, that massive growth has strained major urban centers and exacerbated housing shortages. In the 12 months to March, 4 to 5 international migrants arrived in Canada for every newly started unit of housing construction. That’s the highest ratio of new Canadians to new homes on record in data going back to 1977.

Many Canadians now criticize the government for not only doing too little to boost supply, but also making it worse by adding too much demand from immigration. But Miller pushed back against that view.

“We have to get away from this notion that immigrants are the major cause of housing pressures and the increase in home prices,” he said. “We tend not to think in longer historical arcs or in generational terms, but if people want dental care, health care and affordable housing that they expect, the best way to do that is to get that skilled labor in this country.”

On Wednesday, National Bank Financial’s Chief Economist Stefane Marion called on the government to revise its immigration policy until housing construction catches up with demand. Marion said the government’s decision to open the “immigration floodgates” led to a “record imbalance” between housing supply and demand, and homebuilders can’t keep up with the influx.

A recent survey by Ottawa-based Abacus Data showed 61% of respondents believed Canada’s immigration target is too high, and 63% of them said the number of immigrants coming to the country was having a negative impact on housing.

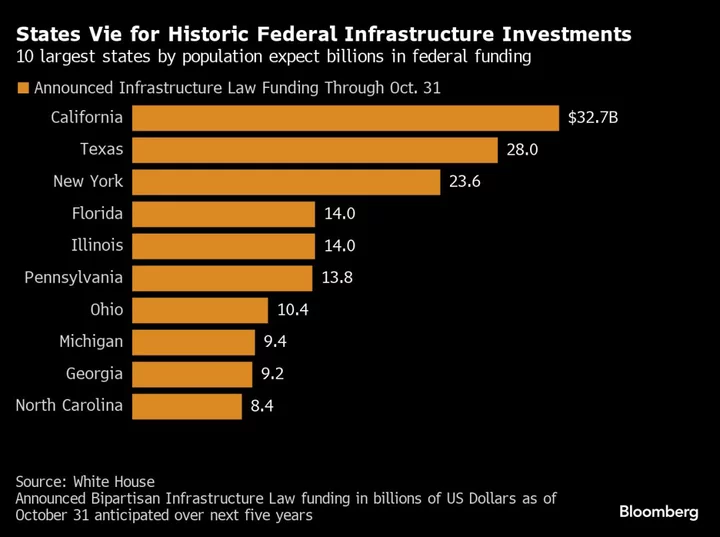

“What’s driving this is really rational concerns, not xenophobia,” said David Coletto, Abacus Data’s chief executive officer. “From many people’s perspective, the growth that Canada experienced hasn’t been matched with an increase in infrastructure. It’s putting a strain on public opinion toward immigration more broadly. We’d be foolish to assume that Canada’s immune to the same forces that have affected other countries.”

In another survey published in July, 39% of respondents said they would be more likely to vote for a political party that promised to reduce immigration numbers. That compared with 24% who said they’d be less likely to do so and 30% who said it’d have no impact. This suggests there may be an appetite for campaigning on reducing immigration, according to Coletto.

Last week in an extensive cabinet shuffle, Trudeau shored up his economic bench and laid some groundwork for future elections as his government faces attacks over the rising cost of living. Sean Fraser was moved from immigration to housing and infrastructure. Miller — who as Crown-Indigenous relations minister quieted some the loudest criticisms of Trudeau on reconciliation — took the reins at immigration.

“Politicians look in electoral cycles. But in my role, we have to look in generational cycles,” Miller said. “Canada needs to address that in a smart way, and that means attracting a younger segment of the population to make sure that people can retire with same expectations and benefits that their parents had. That’s the stark reality of it.”

--With assistance from Erik Hertzberg.

Author: Randy Thanthong-Knight