Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s coalition struggled to agree on major legislation and project funding even before Germany’s highest court issued a surprise judgment this week determining that billions in unused pandemic-era funds could not be transferred into a special pot for climate protection.

Things are now significantly harder. Wednesday’s decision threatens to unravel Scholz’s fragile alliance, or at least force its members — which include his center-left Social Democrats, the fiscally prudent FDP and the Greens — to make painful concessions. They now must find common ground with the CDU/CSU opposition conservatives, who initially brought the lawsuit that prompted the ruling.

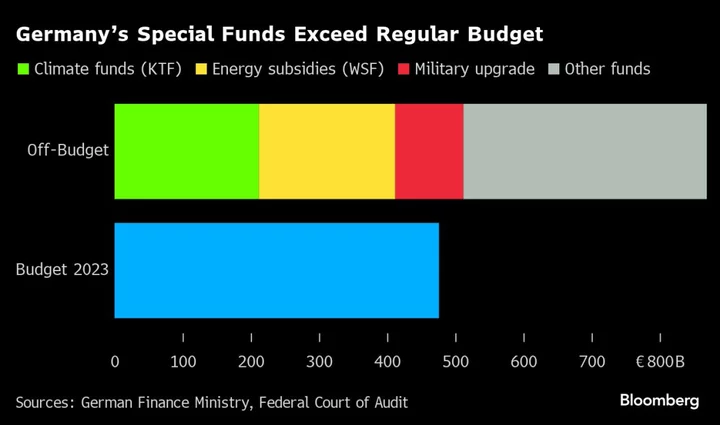

The Federal Constitutional Court’s decision immediately blew a €60 billion ($65.2 billion) hole in spending plans for climate measures and called into question other off-budget vehicles containing about €770 billion of state funding, Bloomberg reported previously.

Officials are also worried the ruling might have downstream effects, including for a €200 billion economic stabilization fund, which conservative opposition leader Friedrich Merz and his CDU/CSU bloc have threatened to target.

Shortly after the ruling, Scholz emerged from a crisis meeting and vowed to find a way to plug the gap. The problem is that there is no obvious way to do so, and fractious relations between the chancellor and his allies will make any compromises difficult.

While a break-up of Scholz’s government is an unlikely scenario, “the ruling will accelerate the disintegration of the coalition,” said Andrea Roemmele, vice president at the Berlin-based Hertie School and a professor of communication in politics.

With the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party riding high in polls, Roemmele believes that the main reason the government will stay intact until the next federal election in 2025 is simply because “all three parties have no real interest in going into new elections in view of their poor ratings in the polls.” The AfD is currently polling second behind the opposition conservatives and is ahead of all three coalition parties, including the Social Democrats.

Moreover, an election wouldn’t change much for the smaller coalition parties. Even if the conservatives were to displace the SPD, the FDP and Greens would still likely end up in government and be forced to fight out their differences. “So that’s not really an attractive alternative,” Roemmele added.

For now, she anticipates that “centrifugal forces will continue to increase and drive the coalition partners further apart.”

Tensions between the FDP and Greens run especially high. While the Greens want to spend big on climate protection measures, the FDP has insisted on adhering to strict borrowing limits and rejecting higher taxes.

Finance Minister Christian Lindner of the FDP has not so far shown any willingness to compromise, telling lawmakers that the ruling marked a “turning point” for fiscal policy, and that the government will now be forced to set stricter priorities when allocating spending.

The Greens are ready to fight for the money, but they may be left with hard choices if the coalition parties stick to their pledge to keep new borrowing within the limits of the constitutionally enshrined debt brake.

In a video posted to social media, Economy Minister Robert Habeck, a Greens party member, said that the €60 billion euros in question had included support for manufacturers struggling with Germany’s green transition, and that Wednesday’s ruling threatens jobs.

“We will work with all our strength in the coming days and weeks to find new answers,” Habeck pledged.

Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, another senior politician from the Greens, made clear that the Greens will push for new resources to make up for the shortfall. “In the fight against the climate crisis,” she said on Wednesday, “we will need these funds.”

Baerbock and Habeck in particular are under a lot of pressure from their base not to give up on climate goals, and will face additional scrutiny next week when the party meets for a four-day convention in Karlsruhe.

Nor can Scholz simply give up on Germany’s ambitious climate agenda. The chancellor will attend COP28 in Dubai at the beginning of December, and Green members are already warning that he can’t go empty-handed. At the summit, Scholz will be questioned about Germany’s commitment to its climate goals and how his planned measures will now be financed, according to a person familiar with the government’s preparations for COP28.

To close the €60 billion gap, Roemmele said, there are only two options. “It’s either reallocating money in the budget and thus cutting expenditure in many other areas — or raising taxes to create new government revenues to plug the budget hole. But Lindner will not support the latter.”

In the wake of the ruling, there has been speculation in Berlin about whether Scholz and the SPD will hold closed-door meetings with Merz and opposition conservatives about a potential collaboration. Scholz has previously called on the CDU/CSU to join forces with the coalition to discuss issues such as migration and cutting bureaucracy at the state level. Such talks could now be expanded to include solving the budget dilemma.

“The question for Merz is whether he will gain political profile or lose political capital with such a cooperation,” Roemmele said.

This week, Wolfgang Schaeuble, Germany’s former finance minister and a well-known fiscal hawk, warned his fellow conservatives against excessive euphoria over Wednesday’s legal victory.

At a special meeting of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group, of which he is the longest-serving member, Schaeuble described the ruling as a slapdown of the coalition and its “sloppy work,” according to participants.

He also said the ruling means that the next government will “in all likelihood” be led by the conservatives. But, he reminded his colleagues, the court’s decision won’t only cut one way – it will also massively restrict the fiscal scope of any future conservative-led coalition.

--With assistance from Karin Matussek, Arne Delfs and Kamil Kowalcze.