A shift in Britain’s mortgage market is delaying the impact of higher interest rates on the economy, increasing the risk of the Bank of England fumbling its decision on how much more it needs to do to curtail inflation.

In previous tightening cycles, most homeowners had floating-rate mortgages that increased within weeks of each BOE rate hike. Now the majority are on fixed-rate deals lasting at two or even five years, insulating them from the bitter medicine the central bank has been administering.

Former BOE officials warned that the change means it will probably take months longer than the traditional 18 months for each increase in borrowing costs to have a full impact on inflation. That complicates the central bank’s next decision on June 22, with this week marking 1 1/2 years since the current round of increases started in December 2021.

The time it takes for rates to pass through to the economy “probably has got significantly longer — not just by a month or two,” said Michael Saunders, senior economic adviser at Oxford Economics, who served on the bank’s Monetary Policy Committee until August. “It just makes it harder for them to calibrate the correct policy path.”

It’s an issue at the top of the agenda for the nine-member Monetary Policy Committee, which is widely expected to raise interest rates again next week and push them to the highest in two decades by the end of the year.

Silvana Tenreyro, due to leave the MPC after this month’s meeting, has warned about the issue in the most graphic terms, evoking Milton Friedman’s “fool in the shower” who scalds himself by being too impatient to wait for the water to warm up.

“There’s always a risk of over-tightening given the lags in monetary policy,” Megan Greene, who will join the MPC after the June 22 meeting, said Tuesday at a hearing in Parliament. Swati Dhingra, a current member of the panel, said in a speech that “The lags in monetary policy transmission imply that there is little we can do to affect inflation in the immediate future.”

The BOE estimates only a third of the rate hikes since the end of 2021 have fed through to consumers and businesses. That, according to economists and former policy makers, suggests the full force of the quickest tightening in four decades will take months more to materialize.

“There’s quite a high probability of making what with hindsight might look like a policy error, but that is just a reflection of the difficulty of calibrating the right response,” Charlie Bean, a former BOE deputy governor, said in an interview. “Assessing how much they need to do is a really difficult judgment call.”

Investors are betting the BOE will raise its key lending rate a more than a full percentage point further to 5.75% by the end of this year, starting with a quarter-point increase on June 22.

Catherine Mann, who is also currently on the MPC, said on Monday that rate increases to date could eventually shave half a percentage point off consumption in the economy and the bank is paying “a lot of attention” to analysis of just how hard those rates will hit.

“We have had a rapid increase in bank rate” Mann said on June 12. “That has been reflected in higher mortgage rates. Households are going to be exposed to significantly higher costs.”

Bean said the “uncertainty about the transmission mechanism, both its size and the speed at which things are passing through” makes policy decisions tricky.

Bailey has acknowledged the difficulty, with a further 1.3 million households will have to refinance fixed-rate mortgages between April and the end of the year.

What Bloomberg Economics Says ...

“April’s shock inflation print has prompted markets to price in a 5.5% terminal rate for the Bank of England. Is the move overdone? We think it might be.”

—Ana Andrade and Dan Hanson, Bloomberg Economics. Click for the INSIGHT.

While the Bank has lifted its base rate by more than 400 basis points since the first hike in December 2021, the average interest rate on all mortgages has risen by just 75 basis points to 2.75%, BOE data shows.

The average rate on new mortgages is up by almost 300 basis points to 4.46%. The implication is that borrowers face a hefty hike in repayments — but only when they are forced to seek new deals.

“I suspect the transmission mechanism is slightly longer than it possibly used to be,” said Ian McCafferty, another former BOE rate-setter. “Now, it’s impossible to know that other than with hindsight ... It’s very difficult to be precise as to how much further they will go.”

The impact of rate rises has also been blunted by fewer homeowners being saddled with mortgage debt. Official data shows 26% of dwellings in England were owned with a mortgage in 2021, down from 32% in 2012.

Mortgage rates cooled after surging in the wake of former Prime Minister Liz Truss’s mini-Budget. However, borrowing costs have started to creep higher again in recent weeks.

The average rate on a five-year fixed deal with a 85% loan-to-value jumped to 5.02% this week, up almost half a percentage point on the previous week, according to Rightmove.

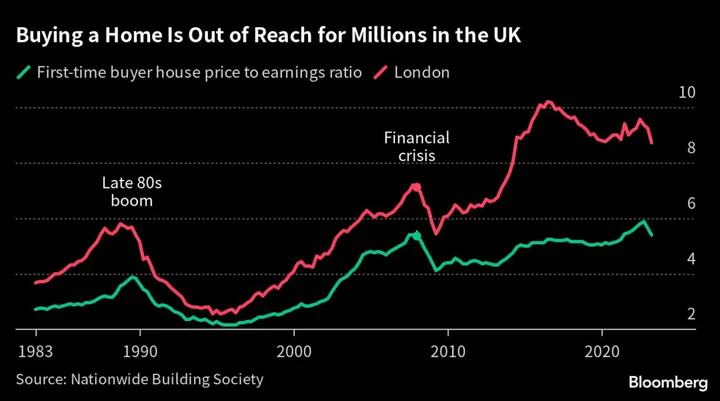

It came as credit ratings agency Fitch warned that mortgage affordability in the UK will slump to its lowest level since 2008 this year after the jump in borrowing cost.

Read more:

- Britain’s Housing Market Is Struggling With More Pain Ahead