Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

The Bank of England this week is likely to forecast a bleak period for the UK economy in the months leading up to the next general election, adding to worries for Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s government.

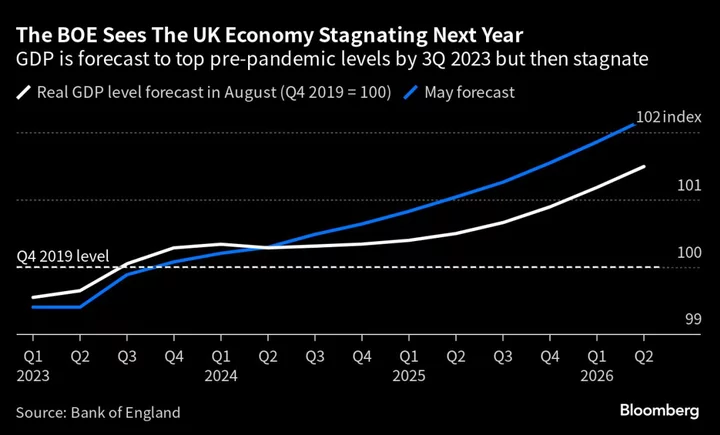

The central bank’s Monetary Policy Committee is set to revise down its estimates for gross domestic product in the second half of this year and early 2024 after surveys and official data pointed to an increased risk of a recession.

A downgrade from the relatively stagnant pace of growth the BOE expected in August would increases the chances of a recession in the coming months. That would be problematic for Sunak, who must call an election before the end of January 2024.

The Conservative Party is currently trailing Labour in polls and has suffered resounding defeats in recent by-elections. Efforts by Sunak to cut government expenditure and ease burdens on business — such as by rowing back on net zero pledges and axing part of Britain’s HS2 rail network — have done little to boost his popularity or stir growth.

What Bloomberg Economics Says ...

“GDP growth has been weaker, the unemployment rate is higher and pay growth is finally easing across all gauges. Financial markets have responded to the recent flow of news by pricing in a smaller-than-50% chance that interest rates reach 5.5%, having seen a peak expectation of over 6% in the summer.”

—Dan Hanson and Ana Andrade, Bloomberg Economics. Click for the PREVIEW.

The BOE’s forecasts, rather than the Bank’s interest rate decision, will take center stage on Thursday, as both investors and economists widely expect the MPC to keep the key rate at 5.25% for a second consecutive meeting. The outlook also is likely to point toward an increase in unemployment to around 5% in the coming months, up from a 50-year low of 3.5% reached last year.

BOE Governor Andrew Bailey, after pushing up interest rates to the highest since 2008, has signaled that borrowing costs won’t be able to fall until inflation is well under control. Britain has the worst inflation problem in the Group of Seven, with prices rising at more than triple the 2% target.

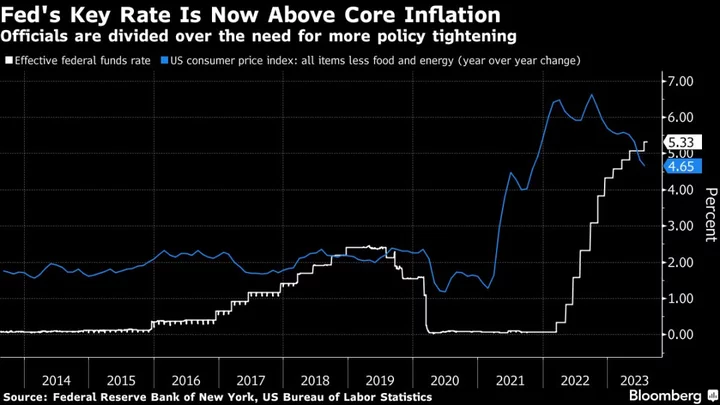

Money markets have recently pared bets on further monetary-policy tightening following signals from the the European Central Bank and US Federal Reserve that rate hikes may have already peaked. That’s lowered the chance of a final BOE quarter-point hike by early next year to around 40% based on swaps tied to policy-meeting dates, while two cuts of 25 basis points each are expected by the end of 2024.

“We see limited likelihood of further hikes being required,” wrote Moyeen Islam, a rates strategist at Barclays Plc, saying the monetary policy report will likely signal policy makers are content with the current level of rates.

This is bearing down on growth. In the minutes of its last meeting in September, the MPC said it expected “GDP to rise by only 0.1% in 2023 Q3, compared with the 0.4% increase incorporated in the August Report.” On top of that, “underlying growth was also likely to be weaker than the 0.25% per quarter built into the August projection for the second half of 2023,” it said.

Most economists expect a cut in the GDP forecast next year from 0.5%, and many expect the BOE to lower this year too.

“For GDP, the near-term profile should be revised down based on recent monthly outturns, and we see the Bank retaining its weak outlook,” said George Buckley, chief UK and euro area economist at Nomura. “As for unemployment, we think there are upside risks to the Bank’s profile.”

Beyond next year, economists think the picture could get a little rosier. Simon French, chief economist at Panmure Gordon, noted recent positive revisions to 2020 and 2021’s GDP level, a reduced risk that inflation expectations were heading higher than reality, and a plateauing of interest rate expectations — all of which have “improved the medium-term outlook.”

More immediately, however, Britain’s inflation rate was 6.7% in September, and increasing numbers of economists are expecting a recession in the coming quarters.

For the MPC, this raises difficulties with maintaining its “Table Mountain” guidance on the path for interest rates — designed to imply that rates would stay high until inflation was under control. Already, political pressure from some members of Parliament is mounting for the BOE to ease off on its restrictive interest rate policy to prevent a contraction in the economy.

Conservative MPs John Barron and David Jones have expressed concern about the impact of high interest rates, and others led by former Prime Minister Liz Truss have urged the government to find ways of bolstering economic growth.

High interest rates complicate Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt’s ambition to deliver tax cuts popular with Conservative voters, as they put pressure on the Treasury purse by driving up debt servicing costs. Lingering inflation has a similar effect, since about a quarter of the UK’s public debt is linked to inflation. Tepid growth, which would hold back the Treasury’s tax receipts, adds to those pressures.

While the BOE is likely to keep rates at 5.25%, investors will be interested to hear what data policy makers are watching most closely.

In September, the MPC’s minutes repeatedly referred to the Purchasing Managers’ Index from S&P Global, which had fallen sharply on a first estimate. This almost certainly contributed to the BOE’s “knife-edge decision to keep the Bank rate unchanged,” Investec’s UK economist Sandra Horsfield said.

The final release, however, saw a substantial upward revision to the services PMI, and the initial reading for October was little-changed from the previous month. The “case for raising rates further now does look somewhat weaker to us that at the last meeting,” Horsfield said.

Wage data has been slightly stronger than expected, emphasizing upside risks for inflation. The BOE’s Chief Economist Huw Pill has indicated that officials thought those figures might be an outlier, and the Office for National Statistics was forced to postpone part of its labor market report due to inadequate data collection.

“There are clear-cut signs that the labor market is cooling far faster than the MPC assumed in August,” said Sanjay Raja, an economist at Deutsche Bank. “It’s very likely that both aggregate wage growth and private sector wage growth have peaked.”

--With assistance from Andrew Atkinson, Tom Rees, James Hirai and Harumi Ichikura.